*/

In October, we celebrate Black excellence. This year, I want to celebrate our Black female silks at the Bar! On 16 March 2020, at Westminster Hall in London, six Black women took silk after being recommended for appointment in the 2019 Queen’s Counsel Competition. They were Krista Lee, Barbara Mills (2025 Chair of the Bar), Allison Munroe, Katharine Newton, Ijeoma Omambala and Melanie Simpson.

These were the first Black women to take silk in over a decade, increasing the numbers several-fold. It was a momentous day in the Bar’s history and suddenly there was great optimism, a sense of shattering ceilings. Robert Buckland KC, the Lord Chancellor presiding over that appointments ceremony, said: ‘Today… is all about esteem. It’s about you as professionals at a high point in your career. It is a public recognition by the Crown – of your excellence, of your experience, and your expertise in your particular fields of law.’

But progress has now stalled. In the latest (2024) KC Competition, none of the ten Black applicants (we do not know how many were women) were successful. Borrowing the title of a speech by the late, great Dr Martin Luther King in 1967, ‘Where do we go from here?’ First, we must honestly recognise where we are now.

What do the statistics tell us? According to Diversity at the Bar 2024, the Bar Standards Board’s (BSB’s) latest published statistics, 617 barristers declared as Black/Black British in December 2023. In contrast with other ethnic groups at the Bar, there is a smaller proportion of barristers from Black/Black British backgrounds compared to the UK working age population (3.6% compared to 5.4%). Similarly, there is also a greater disparity in the proportion of non-KCs from Black/Black British backgrounds compared to the proportion of KCs from the same background (3.6% compared to 1.2%), with the disparity being particularly high for those of Black/Black British – African ethnic backgrounds.

One explanation for these disparities is put forward by the BSB in its report: ‘It may suggest barriers to progression to KC status for practitioners from [Black/Black British] backgrounds.’

What can we, as a legal community working with the Bar Council and BSB, do to generate real and lasting change? It occurred to me that perhaps I ought to talk to the first female Black silk to understand what the barriers were 30 years ago and then speak with the 2019/20 intake to see what, if anything, has changed. What are the critical success factors? How can we make substantive and enduring progress?

I meet Baroness Scotland of Asthal KC in the House of Lords. In 1991 Patricia Scotland, at the age of 35, was appointed Queen’s Counsel – the first Black woman to take silk. I begin by asking what Patricia thinks was the most influential factor in propelling her to silk. ‘It was extremely important to have a supportive and enabling environment,’ she says. ‘Networking with fellow Black female professionals such as accountants, architects, doctors, politicians, journalists and so forth helps to engage in shared experiences and learning.’

Patricia then makes a significant point, which many may not have considered: ‘Of course, the process of your assessment for silk starts well before you make your application. It starts in pupillage. Who was your pupil [supervisor]? What was the quality of the work you were exposed to? Who did your pupil [supervisor] appear before in court? How did you grow the beginning of your career? Who were the solicitors who instructed you?’

Also important is the nurturing you receive during your career: ‘Here the Inns of Court play a crucial part,’ she says. ‘Your Inn is the foundation stone of your professional education.’ Patricia goes on to tell me why she loves her Inn, Middle Temple, which echoes the way I feel about my own Inn, Inner Temple. The point is this: the Inns provide the opportunity to learn and grow, particularly for those from disadvantaged backgrounds who may not be overfamiliar with attending formal dinners, or making submissions before High Court Judges. ‘To young Black barristers reading this article, I say, seize the opportunities that your Inn offers,’ she adds.

Patricia is keen to stress the importance of looking at the progress of all women taking silk compared to men, now that women are entering the profession in similar if not greater numbers than men. However, she accepts that concerns remain about the number of Black women taking silk and generally progressing in the profession. On any analysis of the BSB statistics, the bottom line is that Black female barristers are not taking silk in the same proportions as their White female peers.

So where do we go from here? Most Bar associations are already doing good work but may only have one or two Black barristers who engage. How do we approach the needs of the Black barrister in the most coordinated way, rather than having a silos-within-silos approach? Patricia is keen that we stop reinventing the wheel. ‘We do not need to start from scratch,’ she emphasises, ‘but rather, we look at the need, what resources are already there, then conduct a gap analysis. Who do we need to work with to fill that gap? This in turn gives us a solid strategic plan which can be implemented with measurable outcomes.’

Patricia suggests a needs-based analysis. ‘By this, I mean an analysis of what the Black female [aspiring] silk needs, then an analysis of what the individual barrister specifically needs, followed by an analysis of all the intersectional factors.’

Would it be an idea to have a small group looking at specifically conducting a needs analysis? The answer was a resounding ‘Yes, of course!’

She adds: ‘Identify five key steps that need to be taken to deliver 80% of the results we are looking for. This is the baseline from which any success can be built.’

Patricia points to the work she undertook when Attorney General (AG) to widen access to the AG’s panels of counsel. This was not just lip service, she actively reviewed case work to monitor distribution across those on the panels. There were also programmes offering pre-application information and guidance, as well as mentoring by those already on the panels.

‘You’ll find that most KCs and judges have been appointees to the AG’s panels and public inquiries,’ she says. ‘Moreover, this is taxpayers’ money and there is a positive duty to ensure the government spends it fairly and equally.’

Patricia agrees that a holistic/360 degree and intersectional approach is necessary if we are to swell the numbers of 26 Black silks, eight of whom are women,* over the coming years.

I wonder whether Patricia has any thoughts on the idea of the KC selection process moving to a different model, drawing on those used by other professions. ‘There is an element of subjectivity in assessing the work that we do as barristers,’ Patricia says. ‘However, perhaps it may be more useful to look at whether the current assessment is one of ability, acuity and knowledge, or just an assessment of who you know.’ She commends the requirement for referees to provide demonstrative examples, adding: ‘Perhaps there is an anxiousness surrounding the qualitative nature of the assessments. Is it good enough?’

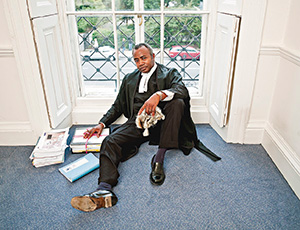

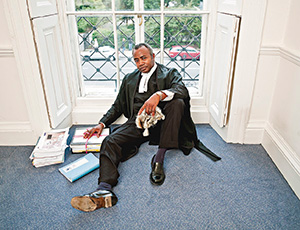

Armed with Patricia’s views, I am keen to talk to some of the historic 2019/20 silk intake to get their perspective. I manage to catch up with Allison Munroe KC of Garden Court Chambers who many will know from her work on some of the most nationally significant inquests and inquiries of our times, including the Hillsborough Inquests and the Grenfell Tower Fire Public Inquiry and UK Covid-19 Inquiry.

How important was her working environment as a future silk? Allison was the first in her family to study at university, and her reply is emphatic: ‘My start at the Bar, in chambers where a third of the tenants were Black, and half were women, was a supportive and enabling experience.’

Among the great Black female barristers with whom she worked were Sandra Graham, Tanoo Mylvaganam, Christiana Hyde, Yaa Yeboah and Janet Plange. All were stars in their fields and extremely well respected in chambers. For Allison, representation matters: ‘Seeing these women made it all seem possible.’ She also praises the number of societies which ‘made an enormous difference, too, in terms of creating a nurturing environment’.

Another factor was the support she received from respected solicitors such as Marcia Willis Stewart KC (Hon) a Managing Partner and Director of Birnberg Peirce Ltd. ‘Marcia is herself a force for embedded change. She has perfected a system of bringing in Black talent, nurturing them and then letting them fly.’

Allison also believes that ‘clerks play a huge and pivotal role in access to quality work which can propel female Black barristers into taking silk’.

She agrees with the growing call for KC competition data to be cut by ethnicity at every stage of the process. ‘Quite frankly, we are beyond the often used explanation that because only ten Black barristers applied we cannot anonymise the data. We need to know whether Black female barristers are not applying in numbers, or whether they are simply not getting through the process. If the former, then clearly more needs to be done at the chambers/Bar Council level. If the latter, the challenge lies with the appointments process itself.’

Allison points to lack of opportunity for Black female barristers to undertake public inquiries and similar quality work where their talents can be showcased, while adding: ‘It is important also to create your own opportunities where possible. In other words, to quote the great Caribbean-American politician Shirley Chisholm, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table bring a folding chair”.’

She sees no bar to assessors from KCA observing applicants in court over a period of time. This brings us back to what Patricia highlighted, that whatever the means of KC assessment, the concern is about its subjective nature. Is it fair and effective?

In terms of initiatives to generate and embed change, Allison suggests this: ‘As a Black barrister community we can run a targeted approach to junior Black barristers across the Bar. Many will not see themselves as silk material and the challenge will be to encourage and guide those promising prospective Black silks.’

Allison believes that if you are not in one of those chambers with a ‘well-oiled silk machinery’, there can be much added benefit in a group offering advice, guidance and encouragement. ‘There is not much planning in most chambers; it is left far too much to the individual to fumble their way to silk. There is clearly a systemic problem.’

Judges are also important. ‘They are the gatekeepers in terms of references,’ says Allison. ‘Again, we do not know at what stage the Black female barrister’s application is failing. As a community we must share information so we can give each other the tools to facilitate reaching those goals.’

Allison points to the plethora of paper and policy initiatives, including the AG’s and other panels of counsel, but says: ‘The reality is that none of it translates into action and therefore real and embedded change.’

Next up, a Black female silk practising exclusively in criminal law. I talk to criminal defence barrister Melanie Simpson KC of 25 Bedford Row, whose complex cases often involve multiple defendants and attract much media attention. She credits self-belief as the most important factor in her taking silk while acknowledging that the hardest part is to get those cases. ‘Chance and luck play a huge part, but by working hard and doing well, the work [should] come,’ she says.

Melanie acknowledges the huge role of Black silks like the late Courtenay Griffiths KC in trying to get fellow Black barristers up that ladder. ‘Unlike when Courtenay first appeared as a silk at the Old Bailey, there are now more Black criminal silks practising at the Old Bailey.’

I point to the disappointing position in relation to Black female civil silks (the overwhelming proportion of silks do civil work, which has the smallest number of women and ethnic minority barristers). ‘It is important to have Black role models at the Bar in senior positions, in silk, and as Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and High Court Judges,’ says Melanie. ‘This is all tied up with feelings of belonging and confidence for up-and-coming Black barristers.’

Statistics show a huge disparity of earnings at the Bar, with Black female barristers earning the least. Melanie says: ‘It is important to have transparent procedures in chambers to monitor distribution of work, which in turn can make a huge difference in closing the earnings gap for Black female barristers.’

Like Patricia, Melanie believes that a 360-degree approach is critical and is in favour of a needs analysis group. ‘At the end of the day, the initiatives we seek are really about achieving fairness,’ she says. ‘Why should a Black barrister have to be twice as good as their White counterpart in order to take silk?’

On KC selection, Melanie accepts that the process could be different. We circle around to Patricia’s point about the subjective nature of qualitative assessment. How do we calibrate this?

Melanie points to the increased success rates of Black silks in chambers which arrange and fund consultants to assist candidates in preparing the KC application form. If some chambers can do it, why not all chambers? ‘All chambers should have positive policies as part of their constitution to assist every member who wants to take silk, to obtain the necessary practical advice and guidance throughout their practice,’ she says.

On a positive note, Melanie agrees that once a needs analysis has been conducted, greater engagement with the Institute of Barristers’ Clerks and the judiciary would be critical. ‘The former is the gatekeeper of access to quality work for the Black barrister, and the latter is the gatekeeper of references.’

It is notable to hear the ‘gatekeeper’ term again. So, do Black barristers face a concrete ceiling when seeking silk and indeed judicial appointment? The answer, I would say, is yes. Patricia puts it best when she says: ‘If the Bar is not taking every single opportunity to enhance and enable all talent to shine, surely we have a profession which is not as great as it could be. At a time when the rule of law and legal systems are under attack, we cannot afford our profession not to have the very best. And the best talent comes in a multiplicity of forms.’

We know talent is everywhere, but opportunity is not and sometimes bold action is needed to create a truly level playing field.

Above (L to R): Baroness Scotland KC on 4 July 2007, the day she was sworn into office as Attorney General, pictured with Jack Straw, the Lord Chancellor; Lord Phillips, the Lord Chief Justice; and Vera Baird KC, the second woman to hold the post of Solicitor General. Patricia Scotland took silk in 1991, the first Black woman to do so, and went on to become a Deputy High Court Judge, the first Black woman to be appointed in that role. She then joined the House of Lords in 1997 to start her political career, most notably as Attorney General 2007-10 – again, the first woman and first person of colour to hold that position. She was Secretary-general of the Commonwealth of Nations 2016-25 and is an associate member of 4pb.

There are 26 Black silks, eight of whom are female, according to Bar Council numbers. Note that the total number of Black silks does not include those who select the category ‘any other mixed or multiple ethnic background’ when providing personal data to King’s Counsel Appointments (KCA). In 2006, the monitoring process was refined to compare declared ethnic minority applicants directly against those who declared themselves as White, excluding those who did not disclose their ethnicity from the analysis. The homogenous BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) acronym is deconstructed in KCA ethnic minority statistics 2017-23. See also the KCA monitoring statistics 1995-2023.

‘The Bar Council’s Race at the Bar: Three years on report presents a mixed narrative: notable advancements in some areas, yet stagnation in others,’ according to a recent article in this magazine and ‘the number of Black KCs remains critically low’. Read Mariam Diaby’s interview with Laurie-Anne Power KC, Jason Pitter KC, Harpreet Sandhu KC, Eleena Misra KC and Simon Regis CBE (Counsel, January 2025).

The current system for the appointment of KCs has been used since the 2005-06 competition, subject to modifications. In 2017 Queen’s Counsel Appointments (QCA) commissioned The Work Foundation to investigate the underapplication by women (Balancing the Scales) and in 2018 an assessment process validation from Jenny Crewe Consulting Ltd. Balancing the Scales found that obtaining judicial references was a distinct barrier for women, who reported dread, stress, anxiety, low confidence and humiliation, as well as the existence of informal power networks from which they were excluded. Male applicants, on the other hand, had little hesitation in approaching judicial assessors in advance and the cherry-picking of references had become commonplace. The Bar Council and Law Society were consulted on the resulting QCA proposals to change the requirements and the process was changed in 2019. Previously, applicants had been asked to provide the names of eight to 12 judicial assessors, six practitioner assessors, and four to six client assessors. From 2019, applicants were asked to list at least one judicial and one practitioner assessor from each of their listed cases, and at least six client assessors.

On 2 October, a celebration of Black advocates at the Bar was held at Gray’s Inn. Co-hosted by Laurie-Anne Power KC and Jason Pitter KC and featuring a panel discussion with Gary Green KC, Allison Munroe KC, Martin Forde KC and Anesta Weeks KC, Black Silk explored why there are so few Black silks, what can be done about it, and how to take forward the legacy and achievements of late friends and colleagues. The event was held in partnership with Garden Court Chambers and began with a short film in honour of the Dr Courtenay Griffiths KC (1955-2025) as well as remembering Michael Hall (1957-2025), the criminal defence barrister who, like Courtenay, helped paved the way for many others to follow.

Diversity at the Bar 2024, Bar Standards Board, 2025

Gross earnings by sex and practice area at the self-employed Bar 2024, Bar Council, 2025

New practitioner earnings at the self-employed Bar 2024, Bar Council, 2025

Balancing the Scales, The Work Foundation, 2017

In October, we celebrate Black excellence. This year, I want to celebrate our Black female silks at the Bar! On 16 March 2020, at Westminster Hall in London, six Black women took silk after being recommended for appointment in the 2019 Queen’s Counsel Competition. They were Krista Lee, Barbara Mills (2025 Chair of the Bar), Allison Munroe, Katharine Newton, Ijeoma Omambala and Melanie Simpson.

These were the first Black women to take silk in over a decade, increasing the numbers several-fold. It was a momentous day in the Bar’s history and suddenly there was great optimism, a sense of shattering ceilings. Robert Buckland KC, the Lord Chancellor presiding over that appointments ceremony, said: ‘Today… is all about esteem. It’s about you as professionals at a high point in your career. It is a public recognition by the Crown – of your excellence, of your experience, and your expertise in your particular fields of law.’

But progress has now stalled. In the latest (2024) KC Competition, none of the ten Black applicants (we do not know how many were women) were successful. Borrowing the title of a speech by the late, great Dr Martin Luther King in 1967, ‘Where do we go from here?’ First, we must honestly recognise where we are now.

What do the statistics tell us? According to Diversity at the Bar 2024, the Bar Standards Board’s (BSB’s) latest published statistics, 617 barristers declared as Black/Black British in December 2023. In contrast with other ethnic groups at the Bar, there is a smaller proportion of barristers from Black/Black British backgrounds compared to the UK working age population (3.6% compared to 5.4%). Similarly, there is also a greater disparity in the proportion of non-KCs from Black/Black British backgrounds compared to the proportion of KCs from the same background (3.6% compared to 1.2%), with the disparity being particularly high for those of Black/Black British – African ethnic backgrounds.

One explanation for these disparities is put forward by the BSB in its report: ‘It may suggest barriers to progression to KC status for practitioners from [Black/Black British] backgrounds.’

What can we, as a legal community working with the Bar Council and BSB, do to generate real and lasting change? It occurred to me that perhaps I ought to talk to the first female Black silk to understand what the barriers were 30 years ago and then speak with the 2019/20 intake to see what, if anything, has changed. What are the critical success factors? How can we make substantive and enduring progress?

I meet Baroness Scotland of Asthal KC in the House of Lords. In 1991 Patricia Scotland, at the age of 35, was appointed Queen’s Counsel – the first Black woman to take silk. I begin by asking what Patricia thinks was the most influential factor in propelling her to silk. ‘It was extremely important to have a supportive and enabling environment,’ she says. ‘Networking with fellow Black female professionals such as accountants, architects, doctors, politicians, journalists and so forth helps to engage in shared experiences and learning.’

Patricia then makes a significant point, which many may not have considered: ‘Of course, the process of your assessment for silk starts well before you make your application. It starts in pupillage. Who was your pupil [supervisor]? What was the quality of the work you were exposed to? Who did your pupil [supervisor] appear before in court? How did you grow the beginning of your career? Who were the solicitors who instructed you?’

Also important is the nurturing you receive during your career: ‘Here the Inns of Court play a crucial part,’ she says. ‘Your Inn is the foundation stone of your professional education.’ Patricia goes on to tell me why she loves her Inn, Middle Temple, which echoes the way I feel about my own Inn, Inner Temple. The point is this: the Inns provide the opportunity to learn and grow, particularly for those from disadvantaged backgrounds who may not be overfamiliar with attending formal dinners, or making submissions before High Court Judges. ‘To young Black barristers reading this article, I say, seize the opportunities that your Inn offers,’ she adds.

Patricia is keen to stress the importance of looking at the progress of all women taking silk compared to men, now that women are entering the profession in similar if not greater numbers than men. However, she accepts that concerns remain about the number of Black women taking silk and generally progressing in the profession. On any analysis of the BSB statistics, the bottom line is that Black female barristers are not taking silk in the same proportions as their White female peers.

So where do we go from here? Most Bar associations are already doing good work but may only have one or two Black barristers who engage. How do we approach the needs of the Black barrister in the most coordinated way, rather than having a silos-within-silos approach? Patricia is keen that we stop reinventing the wheel. ‘We do not need to start from scratch,’ she emphasises, ‘but rather, we look at the need, what resources are already there, then conduct a gap analysis. Who do we need to work with to fill that gap? This in turn gives us a solid strategic plan which can be implemented with measurable outcomes.’

Patricia suggests a needs-based analysis. ‘By this, I mean an analysis of what the Black female [aspiring] silk needs, then an analysis of what the individual barrister specifically needs, followed by an analysis of all the intersectional factors.’

Would it be an idea to have a small group looking at specifically conducting a needs analysis? The answer was a resounding ‘Yes, of course!’

She adds: ‘Identify five key steps that need to be taken to deliver 80% of the results we are looking for. This is the baseline from which any success can be built.’

Patricia points to the work she undertook when Attorney General (AG) to widen access to the AG’s panels of counsel. This was not just lip service, she actively reviewed case work to monitor distribution across those on the panels. There were also programmes offering pre-application information and guidance, as well as mentoring by those already on the panels.

‘You’ll find that most KCs and judges have been appointees to the AG’s panels and public inquiries,’ she says. ‘Moreover, this is taxpayers’ money and there is a positive duty to ensure the government spends it fairly and equally.’

Patricia agrees that a holistic/360 degree and intersectional approach is necessary if we are to swell the numbers of 26 Black silks, eight of whom are women,* over the coming years.

I wonder whether Patricia has any thoughts on the idea of the KC selection process moving to a different model, drawing on those used by other professions. ‘There is an element of subjectivity in assessing the work that we do as barristers,’ Patricia says. ‘However, perhaps it may be more useful to look at whether the current assessment is one of ability, acuity and knowledge, or just an assessment of who you know.’ She commends the requirement for referees to provide demonstrative examples, adding: ‘Perhaps there is an anxiousness surrounding the qualitative nature of the assessments. Is it good enough?’

Armed with Patricia’s views, I am keen to talk to some of the historic 2019/20 silk intake to get their perspective. I manage to catch up with Allison Munroe KC of Garden Court Chambers who many will know from her work on some of the most nationally significant inquests and inquiries of our times, including the Hillsborough Inquests and the Grenfell Tower Fire Public Inquiry and UK Covid-19 Inquiry.

How important was her working environment as a future silk? Allison was the first in her family to study at university, and her reply is emphatic: ‘My start at the Bar, in chambers where a third of the tenants were Black, and half were women, was a supportive and enabling experience.’

Among the great Black female barristers with whom she worked were Sandra Graham, Tanoo Mylvaganam, Christiana Hyde, Yaa Yeboah and Janet Plange. All were stars in their fields and extremely well respected in chambers. For Allison, representation matters: ‘Seeing these women made it all seem possible.’ She also praises the number of societies which ‘made an enormous difference, too, in terms of creating a nurturing environment’.

Another factor was the support she received from respected solicitors such as Marcia Willis Stewart KC (Hon) a Managing Partner and Director of Birnberg Peirce Ltd. ‘Marcia is herself a force for embedded change. She has perfected a system of bringing in Black talent, nurturing them and then letting them fly.’

Allison also believes that ‘clerks play a huge and pivotal role in access to quality work which can propel female Black barristers into taking silk’.

She agrees with the growing call for KC competition data to be cut by ethnicity at every stage of the process. ‘Quite frankly, we are beyond the often used explanation that because only ten Black barristers applied we cannot anonymise the data. We need to know whether Black female barristers are not applying in numbers, or whether they are simply not getting through the process. If the former, then clearly more needs to be done at the chambers/Bar Council level. If the latter, the challenge lies with the appointments process itself.’

Allison points to lack of opportunity for Black female barristers to undertake public inquiries and similar quality work where their talents can be showcased, while adding: ‘It is important also to create your own opportunities where possible. In other words, to quote the great Caribbean-American politician Shirley Chisholm, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table bring a folding chair”.’

She sees no bar to assessors from KCA observing applicants in court over a period of time. This brings us back to what Patricia highlighted, that whatever the means of KC assessment, the concern is about its subjective nature. Is it fair and effective?

In terms of initiatives to generate and embed change, Allison suggests this: ‘As a Black barrister community we can run a targeted approach to junior Black barristers across the Bar. Many will not see themselves as silk material and the challenge will be to encourage and guide those promising prospective Black silks.’

Allison believes that if you are not in one of those chambers with a ‘well-oiled silk machinery’, there can be much added benefit in a group offering advice, guidance and encouragement. ‘There is not much planning in most chambers; it is left far too much to the individual to fumble their way to silk. There is clearly a systemic problem.’

Judges are also important. ‘They are the gatekeepers in terms of references,’ says Allison. ‘Again, we do not know at what stage the Black female barrister’s application is failing. As a community we must share information so we can give each other the tools to facilitate reaching those goals.’

Allison points to the plethora of paper and policy initiatives, including the AG’s and other panels of counsel, but says: ‘The reality is that none of it translates into action and therefore real and embedded change.’

Next up, a Black female silk practising exclusively in criminal law. I talk to criminal defence barrister Melanie Simpson KC of 25 Bedford Row, whose complex cases often involve multiple defendants and attract much media attention. She credits self-belief as the most important factor in her taking silk while acknowledging that the hardest part is to get those cases. ‘Chance and luck play a huge part, but by working hard and doing well, the work [should] come,’ she says.

Melanie acknowledges the huge role of Black silks like the late Courtenay Griffiths KC in trying to get fellow Black barristers up that ladder. ‘Unlike when Courtenay first appeared as a silk at the Old Bailey, there are now more Black criminal silks practising at the Old Bailey.’

I point to the disappointing position in relation to Black female civil silks (the overwhelming proportion of silks do civil work, which has the smallest number of women and ethnic minority barristers). ‘It is important to have Black role models at the Bar in senior positions, in silk, and as Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and High Court Judges,’ says Melanie. ‘This is all tied up with feelings of belonging and confidence for up-and-coming Black barristers.’

Statistics show a huge disparity of earnings at the Bar, with Black female barristers earning the least. Melanie says: ‘It is important to have transparent procedures in chambers to monitor distribution of work, which in turn can make a huge difference in closing the earnings gap for Black female barristers.’

Like Patricia, Melanie believes that a 360-degree approach is critical and is in favour of a needs analysis group. ‘At the end of the day, the initiatives we seek are really about achieving fairness,’ she says. ‘Why should a Black barrister have to be twice as good as their White counterpart in order to take silk?’

On KC selection, Melanie accepts that the process could be different. We circle around to Patricia’s point about the subjective nature of qualitative assessment. How do we calibrate this?

Melanie points to the increased success rates of Black silks in chambers which arrange and fund consultants to assist candidates in preparing the KC application form. If some chambers can do it, why not all chambers? ‘All chambers should have positive policies as part of their constitution to assist every member who wants to take silk, to obtain the necessary practical advice and guidance throughout their practice,’ she says.

On a positive note, Melanie agrees that once a needs analysis has been conducted, greater engagement with the Institute of Barristers’ Clerks and the judiciary would be critical. ‘The former is the gatekeeper of access to quality work for the Black barrister, and the latter is the gatekeeper of references.’

It is notable to hear the ‘gatekeeper’ term again. So, do Black barristers face a concrete ceiling when seeking silk and indeed judicial appointment? The answer, I would say, is yes. Patricia puts it best when she says: ‘If the Bar is not taking every single opportunity to enhance and enable all talent to shine, surely we have a profession which is not as great as it could be. At a time when the rule of law and legal systems are under attack, we cannot afford our profession not to have the very best. And the best talent comes in a multiplicity of forms.’

We know talent is everywhere, but opportunity is not and sometimes bold action is needed to create a truly level playing field.

Above (L to R): Baroness Scotland KC on 4 July 2007, the day she was sworn into office as Attorney General, pictured with Jack Straw, the Lord Chancellor; Lord Phillips, the Lord Chief Justice; and Vera Baird KC, the second woman to hold the post of Solicitor General. Patricia Scotland took silk in 1991, the first Black woman to do so, and went on to become a Deputy High Court Judge, the first Black woman to be appointed in that role. She then joined the House of Lords in 1997 to start her political career, most notably as Attorney General 2007-10 – again, the first woman and first person of colour to hold that position. She was Secretary-general of the Commonwealth of Nations 2016-25 and is an associate member of 4pb.

There are 26 Black silks, eight of whom are female, according to Bar Council numbers. Note that the total number of Black silks does not include those who select the category ‘any other mixed or multiple ethnic background’ when providing personal data to King’s Counsel Appointments (KCA). In 2006, the monitoring process was refined to compare declared ethnic minority applicants directly against those who declared themselves as White, excluding those who did not disclose their ethnicity from the analysis. The homogenous BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) acronym is deconstructed in KCA ethnic minority statistics 2017-23. See also the KCA monitoring statistics 1995-2023.

‘The Bar Council’s Race at the Bar: Three years on report presents a mixed narrative: notable advancements in some areas, yet stagnation in others,’ according to a recent article in this magazine and ‘the number of Black KCs remains critically low’. Read Mariam Diaby’s interview with Laurie-Anne Power KC, Jason Pitter KC, Harpreet Sandhu KC, Eleena Misra KC and Simon Regis CBE (Counsel, January 2025).

The current system for the appointment of KCs has been used since the 2005-06 competition, subject to modifications. In 2017 Queen’s Counsel Appointments (QCA) commissioned The Work Foundation to investigate the underapplication by women (Balancing the Scales) and in 2018 an assessment process validation from Jenny Crewe Consulting Ltd. Balancing the Scales found that obtaining judicial references was a distinct barrier for women, who reported dread, stress, anxiety, low confidence and humiliation, as well as the existence of informal power networks from which they were excluded. Male applicants, on the other hand, had little hesitation in approaching judicial assessors in advance and the cherry-picking of references had become commonplace. The Bar Council and Law Society were consulted on the resulting QCA proposals to change the requirements and the process was changed in 2019. Previously, applicants had been asked to provide the names of eight to 12 judicial assessors, six practitioner assessors, and four to six client assessors. From 2019, applicants were asked to list at least one judicial and one practitioner assessor from each of their listed cases, and at least six client assessors.

On 2 October, a celebration of Black advocates at the Bar was held at Gray’s Inn. Co-hosted by Laurie-Anne Power KC and Jason Pitter KC and featuring a panel discussion with Gary Green KC, Allison Munroe KC, Martin Forde KC and Anesta Weeks KC, Black Silk explored why there are so few Black silks, what can be done about it, and how to take forward the legacy and achievements of late friends and colleagues. The event was held in partnership with Garden Court Chambers and began with a short film in honour of the Dr Courtenay Griffiths KC (1955-2025) as well as remembering Michael Hall (1957-2025), the criminal defence barrister who, like Courtenay, helped paved the way for many others to follow.

Diversity at the Bar 2024, Bar Standards Board, 2025

Gross earnings by sex and practice area at the self-employed Bar 2024, Bar Council, 2025

New practitioner earnings at the self-employed Bar 2024, Bar Council, 2025

Balancing the Scales, The Work Foundation, 2017

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar