*/

If you ever find yourself in Otterlo in the eastern Netherlands, then a visit to the Kröller-Müller Museum is a must. Set in one of the country’s largest national parks, the stylish museum and beautiful sculpture garden showcase the 19th and 20th century art collection of Helene Kröller-Muller, presented to the Dutch nation in 1938.

Part of that collection now provides a substantial chunk of the National Gallery’s first exhibition devoted to Neo-Impressionism, highlighting the revolutionary pointillist technique of an artistic movement which combined works reflecting end-of-the-century domestic, industrial and entertainment scenes, and coupled, for some of the artists, with a commitment to radical politics and social conscience.

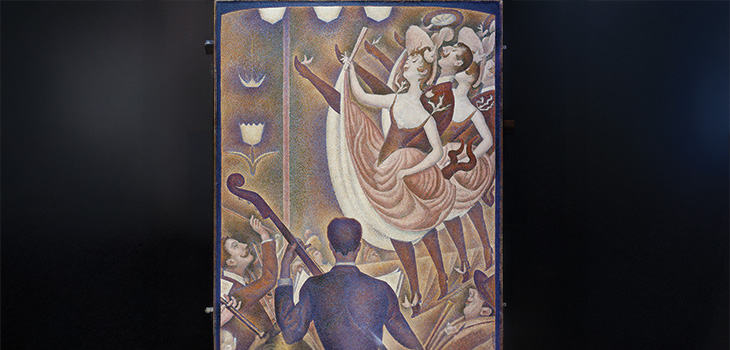

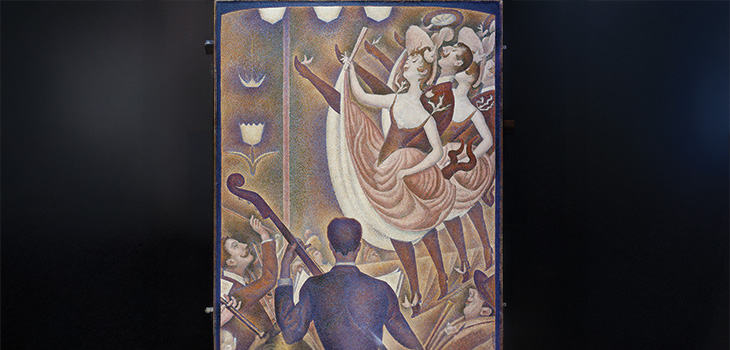

The centrepiece of the show is Georges Seurat’s Le Chahut (a form of cancan dancing), seen for the first time in the UK. Full of exuberant, but geometric, upward thrusts of dancers, orchestra and light sources, and celebrating the entertainment of Paris nightlife and popular culture, there is also something of a sense of alienation and coldness about the painting – and the decidedly creepy image of a man in a hat looking up from the corner at the high kicking dancers. A reflection of modern life indeed. The work dominated attention when first exhibited and, like anything new, it became a prime target for critics. But this painting and the others in this exhibition, with greater emphasis on colour, light and lines, rather than subject matter, helped push the world towards ‘modern art’.

Works by Camille Pissarro, an early adopter who saw the movement as a ‘new phase in the logical march of Impressionism’, and Vincent van Gogh provide valuable context, showing how established artists engaged with Neo-Impressionist principles.

Neo-Impressionists are not always linked with the gritty socialism shown by earlier painters in the 19th century (the National had a small showing of rural painting by Jean-Francois Millet from the 1850s on at the same time). But some of these artists were not simply experimenting with the optical effects of pointillism, they were also reflecting the tough lives of many in the new industrial age. There was a link with anarchist and socialist causes, and a belief that their systematic, scientific approach to painting could contribute to a more rational and equitable society. Paul Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Anna Boch and Jan Toorop all feature. Toorop’s two canvasses Evening (before the Strike) and Morning (after the Strike) luminously depict the anguish and exhaustion of a family worn down by hard labour and strife.

This exhibition demonstrates why Neo-Impressionism matters. It did not portend the end of painting, as some critics claimed, by removing proper brushwork from canvasses and replacing it with a scientific technique of dots. Rather, as one contemporary fan observed, the objective application of colour theory freed these artists to take bold strides in the evolution of art, while preserving radicalism and relevance, and producing work of striking beauty and perspicuity.

If you ever find yourself in Otterlo in the eastern Netherlands, then a visit to the Kröller-Müller Museum is a must. Set in one of the country’s largest national parks, the stylish museum and beautiful sculpture garden showcase the 19th and 20th century art collection of Helene Kröller-Muller, presented to the Dutch nation in 1938.

Part of that collection now provides a substantial chunk of the National Gallery’s first exhibition devoted to Neo-Impressionism, highlighting the revolutionary pointillist technique of an artistic movement which combined works reflecting end-of-the-century domestic, industrial and entertainment scenes, and coupled, for some of the artists, with a commitment to radical politics and social conscience.

The centrepiece of the show is Georges Seurat’s Le Chahut (a form of cancan dancing), seen for the first time in the UK. Full of exuberant, but geometric, upward thrusts of dancers, orchestra and light sources, and celebrating the entertainment of Paris nightlife and popular culture, there is also something of a sense of alienation and coldness about the painting – and the decidedly creepy image of a man in a hat looking up from the corner at the high kicking dancers. A reflection of modern life indeed. The work dominated attention when first exhibited and, like anything new, it became a prime target for critics. But this painting and the others in this exhibition, with greater emphasis on colour, light and lines, rather than subject matter, helped push the world towards ‘modern art’.

Works by Camille Pissarro, an early adopter who saw the movement as a ‘new phase in the logical march of Impressionism’, and Vincent van Gogh provide valuable context, showing how established artists engaged with Neo-Impressionist principles.

Neo-Impressionists are not always linked with the gritty socialism shown by earlier painters in the 19th century (the National had a small showing of rural painting by Jean-Francois Millet from the 1850s on at the same time). But some of these artists were not simply experimenting with the optical effects of pointillism, they were also reflecting the tough lives of many in the new industrial age. There was a link with anarchist and socialist causes, and a belief that their systematic, scientific approach to painting could contribute to a more rational and equitable society. Paul Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Anna Boch and Jan Toorop all feature. Toorop’s two canvasses Evening (before the Strike) and Morning (after the Strike) luminously depict the anguish and exhaustion of a family worn down by hard labour and strife.

This exhibition demonstrates why Neo-Impressionism matters. It did not portend the end of painting, as some critics claimed, by removing proper brushwork from canvasses and replacing it with a scientific technique of dots. Rather, as one contemporary fan observed, the objective application of colour theory freed these artists to take bold strides in the evolution of art, while preserving radicalism and relevance, and producing work of striking beauty and perspicuity.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar