*/

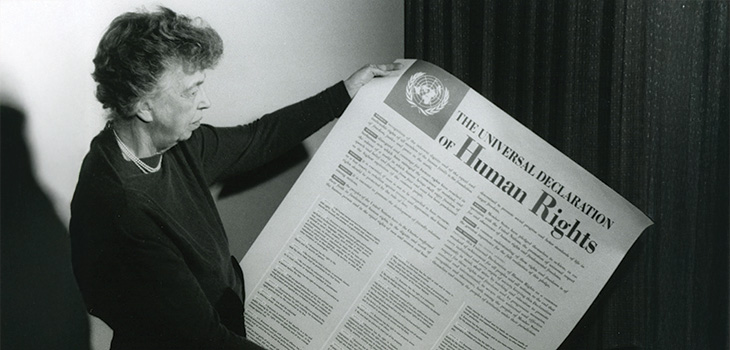

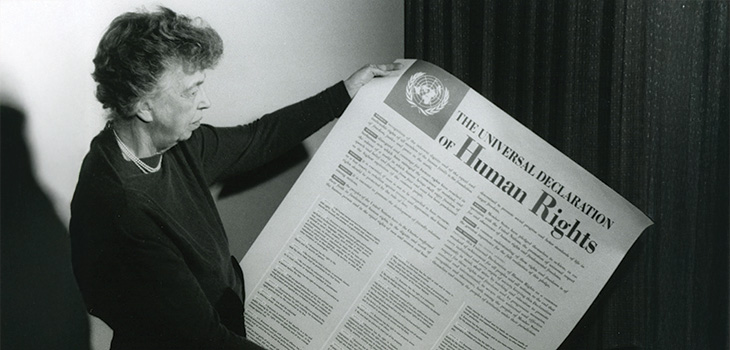

Eleanor Roosevelt (pictured above) told us that our human rights begin in our individual worlds, in our family, in our home, our local community, village, town or city, at our school, college or university and in our place of work and the spaces where we spend our leisure time. As she exhorted, these are the places where we are entitled to seek and find equal justice, equal opportunity and equal dignity without discrimination. Our right to life, liberty and security of our person should be real and tangible in each and every one of these places.

However, these are all places where, on a daily basis, individual dignity is not recognised or respected but instead is ignored, denied or trampled over and where the right to be free from violence is violated. Within our families, within the supposedly safe walls of our homes, in our communities and in the physical spaces and organisational structures and institutions where we study, work and play women and girls experience violence. Individual socio-economic class, wealth, education or academic status does not protect against violence – too often these are tools used to provide cover and impunity.

Such is the pervasive presence of violence against women and girls (VAWG), accounting for almost 20% of all recorded crimes in 2024, that the National Police Chiefs’ Council and the College of Policing described this as a ‘national emergency’ and the Labour Party made a pledge in its election manifesto to halve VAWG over the next ten years. Evidence of practical action to meet this pledge is relatively scant. The government’s formal strategy (the fourth such strategy for tackling VAWG since 2010) was expected sometime this summer but given the government’s failure to allocate money for this in the Spending Review, scepticism may be forgiven.

However, the Bar can be heartened by and take pride in the efforts of the Bar Council, especially over the last eight months under the leadership of our Chair of the Bar, Barbara Mills KC to support efforts within the family and criminal justice systems to tackle VAWG.

Having made widening the debate about VAWG to include the family as well as the criminal justice sector an ambition during her tenure as Vice Chair, Barbara Mills KC restated this as a priority in her inaugural speech on 8 January and has been ‘walking the walk’ since. Discussion among the Bar and with other stakeholders – including roundtables in March and April which I was honoured to attend – to gather information and ideas for the development of a Bar Council policy paper addressing VAWG in the justice sphere is ongoing.

In April the Bar Council submitted written evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee Inquiry ‘Tackling violence against women and girls: funding’. Its efforts to address VAWG and other forms of bullying and harassment within the profession and our places of work continue apace. Indeed, this was a central topic for discussion at the Bar Conference on 7 June which was attended by Baroness Harriet Harman KC who chairs the independent inquiry on bullying and harassment at the Bar commissioned by the Bar Council which is due to report later this month.

Individual barristers and allies continue their inspirational and vital efforts to challenge how VAWG is dealt by the justice systems. Efforts by colleagues to better address VAWG in the Family Court, to develop a roadmap for addressing VAWG, for improving the sentencing and treatment of pregnant women and mothers and the experience of women in seeking appeals within the criminal justice system have all been highlighted in Counsel magazine this year.*

But we can and must ask ourselves and each other ‘what can we as individual barristers and as members of chambers do to prevent, protect and prosecute VAWG?’ It is beyond time and beyond urgent that we answer this resoundingly and effectively.

First, we must scrutinise ourselves and how we practise. We must honestly and fearlessly examine our understanding of ‘violence’ in its many forms, the intersectionality of violence and its manifestations and harms, the stereotypical attitudes we hold and how we utilise stereotypes and tropes to manipulate juries and judges in pursuit of our cases. We must question whether there is any place for the use of such practices in a 21st century justice system – surely there is not? This also places a duty on us to call out the use by others, whether they be judges, lawyers or other professionals, of such practices both within the courtroom and elsewhere.

Similarly, we must equip ourselves with the requisite knowledge and tools to identify when a client is the subject of some sort of VAWG and, to advocate effectively on their behalf. This is particularly necessary when VAWG is not evident on the face of the papers and in respect of coercive control which, by its very nature, often renders a victim unable to recognise and name their experience as such for a significant period of time.

This requires specific training to be developed and undertaken. Perhaps it should be mandatory for anyone involved in criminal or family law work to undertake such training before they are deemed competent to practise in these areas. It may also be vital for practitioners in housing, immigration and/or benefits law to have these skills. Where such training, guidance and tools do not exist, we must be prepared, as some of our colleagues already have, to fill the void by creating training kits and guidance tools – the responsibility is ours. We should ensure that our representatives on local family justice boards and in our respective Bar associations raise at all appropriate opportunities the need for training of judges and other professionals. It must also be our responsibility to provide internal training and support within chambers.

Indeed, care must begin within our professional ‘home’ – chambers. We must look out for and look after each other. VAWG, despite the unacceptable and ignorant utterances of some judges, knows no boundaries of class, education or socio-economic status. It may be hard to contemplate but we must recognise that some of our colleagues, some members of our staff, may be experiencing domestic abuse. We must be able to recognise this when we see it and be prepared to provide appropriate support.

We must accept that violence against female pupils and junior members of the Bar has been, and is, a real issue and that junior female members of staff can also be at particular risk. While we should and will follow the recommendations of the Harman Review, we do not need a formal review to tell us that we must act to prevent this sort of behaviour and implement protective systems. Some measures might include ensuring that every pupil has two supervisors, one female and one male. Alternatively, or additionally, it might be appropriate that an appropriate number of barristers are trained and assigned the role of ‘pastoral mentor’ and a safe contact for staff members.

Pupil supervisors and members of chambers holding a position of authority should undergo rigorous and challenging training about VAWG before they are approved to hold office. Ideally, this sort of training should be undertaken by every member of chambers. To support any such efforts to mould behaviour and encourage an open atmosphere in which individuals feel safe enough to voice their experience, there must be clear policies and procedures and effective enforcement, without repercussion for the victim. Barristers and staff must be able to have confidence that any complaint will be taken seriously, dealt with fairly and as expeditiously as possible.

Finally, as individuals we need to be vigilant that our behaviour in the personal, as well as the professional sphere, is that becoming of a member of the Bar, behaviour that does not tolerate or encourage VAWG. We must raise our children to understand and respect the inherent dignity that each of us should be accorded, that we are all united in a desire to love and be loved, to be respected and treated kindly, and that our autonomy, agency and the sanctity of our person is to be respected and never violated.

We must speak out. We must protect. We must be the change that we all need to see.

See also the Bar Council’s written evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee Inquiry.

* Recent Counsel articles:

‘‘He said, she said’, Dr Charlotte Proudman, Counsel June 2025.

‘Sentencing of pregnant women: a 21st century approach’, Maya Sikand KC and Janey Starling, Counsel March 2025.

‘Safeguarding aspiring barristers’, Sam Mercer and Rachel Krys, Counsel May 2025.

‘VAWG: an effective roadmap to justice’, Dr Charlotte Proudman, Counsel March 2025.

‘A system in crisis – the voices of the silent’, Emma Torr, Counsel February 2025.

‘Breaking the cycle of reoffending – ISC pilot’, Chloe Ashley and District Judge Michelle Smith, Counsel December 2024.

Pictured top: As US delegate to the United Nations General Assembly from 1945 to 1952, Eleanor Roosevelt took a leading role in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Speaking in 1958 on its tenth anniversary, Roosevelt said: ‘Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person... Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.’

Eleanor Roosevelt (pictured above) told us that our human rights begin in our individual worlds, in our family, in our home, our local community, village, town or city, at our school, college or university and in our place of work and the spaces where we spend our leisure time. As she exhorted, these are the places where we are entitled to seek and find equal justice, equal opportunity and equal dignity without discrimination. Our right to life, liberty and security of our person should be real and tangible in each and every one of these places.

However, these are all places where, on a daily basis, individual dignity is not recognised or respected but instead is ignored, denied or trampled over and where the right to be free from violence is violated. Within our families, within the supposedly safe walls of our homes, in our communities and in the physical spaces and organisational structures and institutions where we study, work and play women and girls experience violence. Individual socio-economic class, wealth, education or academic status does not protect against violence – too often these are tools used to provide cover and impunity.

Such is the pervasive presence of violence against women and girls (VAWG), accounting for almost 20% of all recorded crimes in 2024, that the National Police Chiefs’ Council and the College of Policing described this as a ‘national emergency’ and the Labour Party made a pledge in its election manifesto to halve VAWG over the next ten years. Evidence of practical action to meet this pledge is relatively scant. The government’s formal strategy (the fourth such strategy for tackling VAWG since 2010) was expected sometime this summer but given the government’s failure to allocate money for this in the Spending Review, scepticism may be forgiven.

However, the Bar can be heartened by and take pride in the efforts of the Bar Council, especially over the last eight months under the leadership of our Chair of the Bar, Barbara Mills KC to support efforts within the family and criminal justice systems to tackle VAWG.

Having made widening the debate about VAWG to include the family as well as the criminal justice sector an ambition during her tenure as Vice Chair, Barbara Mills KC restated this as a priority in her inaugural speech on 8 January and has been ‘walking the walk’ since. Discussion among the Bar and with other stakeholders – including roundtables in March and April which I was honoured to attend – to gather information and ideas for the development of a Bar Council policy paper addressing VAWG in the justice sphere is ongoing.

In April the Bar Council submitted written evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee Inquiry ‘Tackling violence against women and girls: funding’. Its efforts to address VAWG and other forms of bullying and harassment within the profession and our places of work continue apace. Indeed, this was a central topic for discussion at the Bar Conference on 7 June which was attended by Baroness Harriet Harman KC who chairs the independent inquiry on bullying and harassment at the Bar commissioned by the Bar Council which is due to report later this month.

Individual barristers and allies continue their inspirational and vital efforts to challenge how VAWG is dealt by the justice systems. Efforts by colleagues to better address VAWG in the Family Court, to develop a roadmap for addressing VAWG, for improving the sentencing and treatment of pregnant women and mothers and the experience of women in seeking appeals within the criminal justice system have all been highlighted in Counsel magazine this year.*

But we can and must ask ourselves and each other ‘what can we as individual barristers and as members of chambers do to prevent, protect and prosecute VAWG?’ It is beyond time and beyond urgent that we answer this resoundingly and effectively.

First, we must scrutinise ourselves and how we practise. We must honestly and fearlessly examine our understanding of ‘violence’ in its many forms, the intersectionality of violence and its manifestations and harms, the stereotypical attitudes we hold and how we utilise stereotypes and tropes to manipulate juries and judges in pursuit of our cases. We must question whether there is any place for the use of such practices in a 21st century justice system – surely there is not? This also places a duty on us to call out the use by others, whether they be judges, lawyers or other professionals, of such practices both within the courtroom and elsewhere.

Similarly, we must equip ourselves with the requisite knowledge and tools to identify when a client is the subject of some sort of VAWG and, to advocate effectively on their behalf. This is particularly necessary when VAWG is not evident on the face of the papers and in respect of coercive control which, by its very nature, often renders a victim unable to recognise and name their experience as such for a significant period of time.

This requires specific training to be developed and undertaken. Perhaps it should be mandatory for anyone involved in criminal or family law work to undertake such training before they are deemed competent to practise in these areas. It may also be vital for practitioners in housing, immigration and/or benefits law to have these skills. Where such training, guidance and tools do not exist, we must be prepared, as some of our colleagues already have, to fill the void by creating training kits and guidance tools – the responsibility is ours. We should ensure that our representatives on local family justice boards and in our respective Bar associations raise at all appropriate opportunities the need for training of judges and other professionals. It must also be our responsibility to provide internal training and support within chambers.

Indeed, care must begin within our professional ‘home’ – chambers. We must look out for and look after each other. VAWG, despite the unacceptable and ignorant utterances of some judges, knows no boundaries of class, education or socio-economic status. It may be hard to contemplate but we must recognise that some of our colleagues, some members of our staff, may be experiencing domestic abuse. We must be able to recognise this when we see it and be prepared to provide appropriate support.

We must accept that violence against female pupils and junior members of the Bar has been, and is, a real issue and that junior female members of staff can also be at particular risk. While we should and will follow the recommendations of the Harman Review, we do not need a formal review to tell us that we must act to prevent this sort of behaviour and implement protective systems. Some measures might include ensuring that every pupil has two supervisors, one female and one male. Alternatively, or additionally, it might be appropriate that an appropriate number of barristers are trained and assigned the role of ‘pastoral mentor’ and a safe contact for staff members.

Pupil supervisors and members of chambers holding a position of authority should undergo rigorous and challenging training about VAWG before they are approved to hold office. Ideally, this sort of training should be undertaken by every member of chambers. To support any such efforts to mould behaviour and encourage an open atmosphere in which individuals feel safe enough to voice their experience, there must be clear policies and procedures and effective enforcement, without repercussion for the victim. Barristers and staff must be able to have confidence that any complaint will be taken seriously, dealt with fairly and as expeditiously as possible.

Finally, as individuals we need to be vigilant that our behaviour in the personal, as well as the professional sphere, is that becoming of a member of the Bar, behaviour that does not tolerate or encourage VAWG. We must raise our children to understand and respect the inherent dignity that each of us should be accorded, that we are all united in a desire to love and be loved, to be respected and treated kindly, and that our autonomy, agency and the sanctity of our person is to be respected and never violated.

We must speak out. We must protect. We must be the change that we all need to see.

See also the Bar Council’s written evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee Inquiry.

* Recent Counsel articles:

‘‘He said, she said’, Dr Charlotte Proudman, Counsel June 2025.

‘Sentencing of pregnant women: a 21st century approach’, Maya Sikand KC and Janey Starling, Counsel March 2025.

‘Safeguarding aspiring barristers’, Sam Mercer and Rachel Krys, Counsel May 2025.

‘VAWG: an effective roadmap to justice’, Dr Charlotte Proudman, Counsel March 2025.

‘A system in crisis – the voices of the silent’, Emma Torr, Counsel February 2025.

‘Breaking the cycle of reoffending – ISC pilot’, Chloe Ashley and District Judge Michelle Smith, Counsel December 2024.

Pictured top: As US delegate to the United Nations General Assembly from 1945 to 1952, Eleanor Roosevelt took a leading role in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Speaking in 1958 on its tenth anniversary, Roosevelt said: ‘Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person... Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.’

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar