*/

Britain has a rich tradition of producing leading lawyers who have shaped international criminal law. Nevertheless, to many members of the Bar, this field may appear mysterious or impenetrable. This article provides practical guidance on how you could build an international criminal practice, with a focus on the International Criminal Court (ICC). Practising opportunities have admittedly declined since a peak of around 15 years ago when there were more international tribunals than today. But the field remains resilient. Accountability initiatives emerge for every new armed conflict, so professional opportunities continue to appear. Members of the English and Welsh Bar should be well-placed to take these opportunities given how valuable their specialist litigation and advocacy skills are for this practice area.

International criminal law is a relatively new branch of international law that seeks to hold individuals criminally accountable for crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The international community first conducted such prosecutions at Nuremberg and Tokyo following the Second World War, and then again in the 1990s at tribunals established after conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda. A permanent international court, the ICC was created in 1998 to ensure that a forum to prosecute international crimes always exists, although this court can only exercise jurisdiction when the crimes are perpetrated on the territory of a state party or by one of their nationals, and when national authorities are unwilling or unable to conduct prosecutions themselves. The United Kingdom, along with 124 other countries, are states parties to the court. Despite the existence of the ICC, other tribunals continue to be created to address accountability issues falling outside of the ICC’s jurisdiction, including a recently announced special tribunal to prosecute aggression against Ukraine.

Opportunities can be distinguished between employed roles or roles for self-employed practitioners. The prosecution function is carried out by lawyers employed by the tribunal, led by an elected (or appointed) chief prosecutor. International judges have legal officers who are also employed lawyers. These positions are advertised on the websites of the tribunals, and they involve a competitive recruitment process like Civil Service jobs.

The function of representing accused persons, victims or governments in proceedings is usually carried out by self-employed practitioners. To represent such clients, you need to be admitted to the list of counsel at the relevant tribunal, which is discussed below. Accused and victims are often indigent, meaning that their legal teams are funded by legal aid (see the ICC’s legal aid policy). Representing accused persons or victims is an undertaking that may involve several years of full-time work, given the scale of allegations and length of proceedings.

Tribunals also need a wide range of inhouse legal officers not specialising in crime. This includes lawyers in employment law, contract law and international public and institutional law to manage the administrative functioning of the organisation. These opportunities are also advertised on the tribunals’ websites.

If you wish to represent clients as an independent practitioner, you must be admitted to practise at the relevant court or tribunal. There is no universal international Bar; each tribunal independently regulates the admission of counsel appearing before them. The admission requirements often rely on your membership of a domestic Bar in combination with a certain number of years of criminal law experience. At the ICC, you must demonstrate ten years’ experience in ‘criminal proceedings as a judge, prosecutor, advocate or in other similar capacity’ to be admitted as lead counsel. You can also be admitted to the list as associate counsel, for which you need eight years’ experience. Application forms and guides to join the list of counsel at the ICC can be found here.

Being admitted is far from a guarantee of being instructed. At the ICC, there are hundreds of counsel on the list yet only a handful of new cases each year at best. Here are some ideas to increase the odds of being instructed; note the differing dynamics of how counsel for the defence/victims are selected.

For the defence, suspects are responsible for directly choosing their lead counsel, which usually happens after they are arrested and transferred to The Hague. Spoilt for choice, suspects tend to select someone who has previously been lead or associate counsel at the ICC or another tribunal. Your more realistic entry point, therefore, may be as associate counsel or in a non-counsel supporting role and then working your way up. This involves networking with and applying to the appointed lead counsel, who has wide discretion in selecting other team members. You can find out who the lead counsel is through the case record, and you can often find their contact details through their law firm or chambers. The best moments to approach lead counsel are just after their appointment (when they are still building their team) and when charges are confirmed for trial (when the legal aid allocation increases). You have a better chance of recruitment to a team if you can demonstrate international litigation experience, and there are suggestions below on how to acquire this.

In principle, victims also get free choice of counsel (called ‘legal representatives’). But there are potentially thousands of victims participating in proceedings, so the judges usually appoint common legal representatives to represent groups of victims. When and how this happens differs case to case, and the judges have the option of appointing external independent practitioners or the ICC’s inhouse victims’ representation office (called the Office of Public Counsel for the Victims ((OPCV)). You could try joining an existing team by contacting an appointed legal representative or by applying for employed positions with OPCV. But if you wish to be instructed as a legal representative yourself, at least two factors appear to increase your chances. The first is if you have previous experience as a legal representative. The second is if you already represent the participating victims in another capacity. To this end, some victims’ lawyers work with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) long before any proceedings at the ICC have even started to help victims of atrocities. They advocate on behalf of these victims and lobby the ICC prosecutor to initiate investigations into their crimes. This is a long-term strategy that might never even result in any proceedings, but the work is rewarding in and of itself, and some NGOs may provide funding for it. If proceedings do eventually commence, those victims’ lawyers are well positioned to be appointed legal representatives in the case.

Whichever route you take, building up international litigation experience is essential to sell yourself to lead counsel or clients. Counsel can do this through acquiring shorter-term assignments at the ICC, including appointments as:

These assignments typically last between a week and a month, and the selection is usually made by the ICC’s registry (rather than the client), based on factors such as rotation, availability and proximity of counsel. Be sure to indicate that you are willing to take on these types of assignments when applying for admission to the list of counsel.

For those who can take a three-to-six months’ break from practising, you could also apply to be a ‘visiting professional’ at the ICC with one of the inhouse offices, such as the defence office (called the Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD)). Opportunities are advertised on the ICC website.

For those early enough in their careers, they could apply for a role supporting counsel. At the ICC, you can be an assistant to counsel with five years’ domestic criminal law experience, or a legal assistant or case manager with two years’ experience. Despite their titles, these are substantive legal roles in which you will likely have significant responsibilities and reasonable remuneration (see ICC legal aid policy, pp 38-39). Each defence or victims’ team is responsible for recruiting these positions, so keep an eye out for vacancies on professional social media platforms or lead counsel’s law firm or chambers websites. Applicants have had success with good speculative applications as well. For those with less than three years’ experience, internships are also available and are advertised on the ICC website.

We are lucky that the Bar has many established (and ranked) international criminal practitioners, who may be amenable to giving advice if you reach out. If you are interested in attending a conference, the International Bar Association’s War Crimes Committee holds a great annual conference in The Hague each spring. Lastly, it is also advisable to get involved with the ICC Bar Association and run for one of its many committees to network with global practitioners, stay up-to-date with latest developments and contribute to influencing policy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not reflect the views of the International Criminal Court.

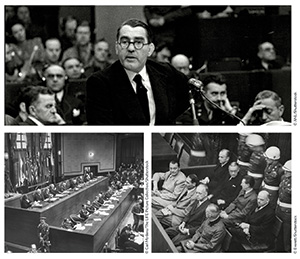

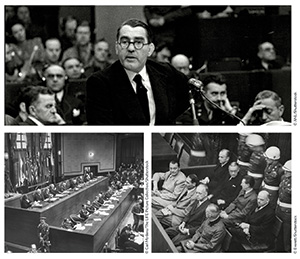

Clockwise from top: Slobodan Milosevic, former President of Yugoslavia, at the start of his trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), The Hague, 13 February 2002. | The ICTY in The Hague was established in 1993, ran for 24 years and concluded in 2017. | The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established in 1994 with its seat in Arusha, Tanzania and concluded in 2014.

Legal aid policy of the International Criminal Court (adopted December 2023)

Application forms and guidance to join the list of counsel at the ICC

Duty counsel – see reg 73, Regulations of the court

Rule 74 adviser – see r 74, Rules of evidence and procedure

Article 55 and article 56 counsel – see arts 55 and 56, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

Britain has a rich tradition of producing leading lawyers who have shaped international criminal law. Nevertheless, to many members of the Bar, this field may appear mysterious or impenetrable. This article provides practical guidance on how you could build an international criminal practice, with a focus on the International Criminal Court (ICC). Practising opportunities have admittedly declined since a peak of around 15 years ago when there were more international tribunals than today. But the field remains resilient. Accountability initiatives emerge for every new armed conflict, so professional opportunities continue to appear. Members of the English and Welsh Bar should be well-placed to take these opportunities given how valuable their specialist litigation and advocacy skills are for this practice area.

International criminal law is a relatively new branch of international law that seeks to hold individuals criminally accountable for crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The international community first conducted such prosecutions at Nuremberg and Tokyo following the Second World War, and then again in the 1990s at tribunals established after conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda. A permanent international court, the ICC was created in 1998 to ensure that a forum to prosecute international crimes always exists, although this court can only exercise jurisdiction when the crimes are perpetrated on the territory of a state party or by one of their nationals, and when national authorities are unwilling or unable to conduct prosecutions themselves. The United Kingdom, along with 124 other countries, are states parties to the court. Despite the existence of the ICC, other tribunals continue to be created to address accountability issues falling outside of the ICC’s jurisdiction, including a recently announced special tribunal to prosecute aggression against Ukraine.

Opportunities can be distinguished between employed roles or roles for self-employed practitioners. The prosecution function is carried out by lawyers employed by the tribunal, led by an elected (or appointed) chief prosecutor. International judges have legal officers who are also employed lawyers. These positions are advertised on the websites of the tribunals, and they involve a competitive recruitment process like Civil Service jobs.

The function of representing accused persons, victims or governments in proceedings is usually carried out by self-employed practitioners. To represent such clients, you need to be admitted to the list of counsel at the relevant tribunal, which is discussed below. Accused and victims are often indigent, meaning that their legal teams are funded by legal aid (see the ICC’s legal aid policy). Representing accused persons or victims is an undertaking that may involve several years of full-time work, given the scale of allegations and length of proceedings.

Tribunals also need a wide range of inhouse legal officers not specialising in crime. This includes lawyers in employment law, contract law and international public and institutional law to manage the administrative functioning of the organisation. These opportunities are also advertised on the tribunals’ websites.

If you wish to represent clients as an independent practitioner, you must be admitted to practise at the relevant court or tribunal. There is no universal international Bar; each tribunal independently regulates the admission of counsel appearing before them. The admission requirements often rely on your membership of a domestic Bar in combination with a certain number of years of criminal law experience. At the ICC, you must demonstrate ten years’ experience in ‘criminal proceedings as a judge, prosecutor, advocate or in other similar capacity’ to be admitted as lead counsel. You can also be admitted to the list as associate counsel, for which you need eight years’ experience. Application forms and guides to join the list of counsel at the ICC can be found here.

Being admitted is far from a guarantee of being instructed. At the ICC, there are hundreds of counsel on the list yet only a handful of new cases each year at best. Here are some ideas to increase the odds of being instructed; note the differing dynamics of how counsel for the defence/victims are selected.

For the defence, suspects are responsible for directly choosing their lead counsel, which usually happens after they are arrested and transferred to The Hague. Spoilt for choice, suspects tend to select someone who has previously been lead or associate counsel at the ICC or another tribunal. Your more realistic entry point, therefore, may be as associate counsel or in a non-counsel supporting role and then working your way up. This involves networking with and applying to the appointed lead counsel, who has wide discretion in selecting other team members. You can find out who the lead counsel is through the case record, and you can often find their contact details through their law firm or chambers. The best moments to approach lead counsel are just after their appointment (when they are still building their team) and when charges are confirmed for trial (when the legal aid allocation increases). You have a better chance of recruitment to a team if you can demonstrate international litigation experience, and there are suggestions below on how to acquire this.

In principle, victims also get free choice of counsel (called ‘legal representatives’). But there are potentially thousands of victims participating in proceedings, so the judges usually appoint common legal representatives to represent groups of victims. When and how this happens differs case to case, and the judges have the option of appointing external independent practitioners or the ICC’s inhouse victims’ representation office (called the Office of Public Counsel for the Victims ((OPCV)). You could try joining an existing team by contacting an appointed legal representative or by applying for employed positions with OPCV. But if you wish to be instructed as a legal representative yourself, at least two factors appear to increase your chances. The first is if you have previous experience as a legal representative. The second is if you already represent the participating victims in another capacity. To this end, some victims’ lawyers work with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) long before any proceedings at the ICC have even started to help victims of atrocities. They advocate on behalf of these victims and lobby the ICC prosecutor to initiate investigations into their crimes. This is a long-term strategy that might never even result in any proceedings, but the work is rewarding in and of itself, and some NGOs may provide funding for it. If proceedings do eventually commence, those victims’ lawyers are well positioned to be appointed legal representatives in the case.

Whichever route you take, building up international litigation experience is essential to sell yourself to lead counsel or clients. Counsel can do this through acquiring shorter-term assignments at the ICC, including appointments as:

These assignments typically last between a week and a month, and the selection is usually made by the ICC’s registry (rather than the client), based on factors such as rotation, availability and proximity of counsel. Be sure to indicate that you are willing to take on these types of assignments when applying for admission to the list of counsel.

For those who can take a three-to-six months’ break from practising, you could also apply to be a ‘visiting professional’ at the ICC with one of the inhouse offices, such as the defence office (called the Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD)). Opportunities are advertised on the ICC website.

For those early enough in their careers, they could apply for a role supporting counsel. At the ICC, you can be an assistant to counsel with five years’ domestic criminal law experience, or a legal assistant or case manager with two years’ experience. Despite their titles, these are substantive legal roles in which you will likely have significant responsibilities and reasonable remuneration (see ICC legal aid policy, pp 38-39). Each defence or victims’ team is responsible for recruiting these positions, so keep an eye out for vacancies on professional social media platforms or lead counsel’s law firm or chambers websites. Applicants have had success with good speculative applications as well. For those with less than three years’ experience, internships are also available and are advertised on the ICC website.

We are lucky that the Bar has many established (and ranked) international criminal practitioners, who may be amenable to giving advice if you reach out. If you are interested in attending a conference, the International Bar Association’s War Crimes Committee holds a great annual conference in The Hague each spring. Lastly, it is also advisable to get involved with the ICC Bar Association and run for one of its many committees to network with global practitioners, stay up-to-date with latest developments and contribute to influencing policy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not reflect the views of the International Criminal Court.

Clockwise from top: Slobodan Milosevic, former President of Yugoslavia, at the start of his trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), The Hague, 13 February 2002. | The ICTY in The Hague was established in 1993, ran for 24 years and concluded in 2017. | The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established in 1994 with its seat in Arusha, Tanzania and concluded in 2014.

Legal aid policy of the International Criminal Court (adopted December 2023)

Application forms and guidance to join the list of counsel at the ICC

Duty counsel – see reg 73, Regulations of the court

Rule 74 adviser – see r 74, Rules of evidence and procedure

Article 55 and article 56 counsel – see arts 55 and 56, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar