*/

‘On 24 February 2022 Russia invaded Ukraine. Within a week, and having acted for Ukraine before, I was asked if, together with Quinn Emmanuel [QE], I would lead a case for Ukraine against Russia in the European Court of Human Rights seeking to establish full accountability for the war. And would I do it pro bono?

‘I said yes as it seemed the right thing to do. Together with Lord Verdirame KC I put together a team of 11 brilliant juniors from Blackstone and Twenty Essex, working together with the QE team. We filed the first round of submissions in the case within months of the war starting and went from there.’

Tim Otty KC of Blackstone Chambers, Barrister of the Year 2023, is talking about the beginning of Ukraine and the Netherlands v Russia. Following a hearing in June 2024, in July of this year the Grand Chamber delivered its judgment. Russia was found accountable for systematic and flagrant violations across Ukraine, violations including indiscriminate military attacks, summary execution of civilians, torture including the use of rape as a weapon of war, arbitrary detentions and property damage on a massive, unprecedented scale.

Back to the start. ‘In March 2022 the first challenge was to capture in real time the sheer scale of what was happening. We had different members of the legal team working across the world 24 hours a day to build a master chronology to record every reported incident as it occurred.

‘The biggest challenge legally was to show that all victims of Russia’s attacks were within its jurisdiction for Convention purposes even in territory not occupied by Russia.

‘Would it be possible to hold Russia to account for bombing and missile attacks across the country as well as for the atrocities in Bucha and elsewhere?

‘And to win this argument we would need to persuade the Grand Chamber to overrule or distinguish a line of case law going back to the early 2000s.

‘We argued that all victims of Russian attacks, wherever they were, had to be held to be within Russian jurisdiction and sought to emphasise that this was the first instance of full-scale war in Europe since 1945, and that Russia’s attempt to eliminate a sovereign state through its attacks made this a case apart.

‘In an endeavour to give the court comfort in taking this new course we sought to get other state signatories to intervene in the proceedings in our support. Twenty-six did. Our argument carried the day.

‘The case was clear cut on the merits but by no means so on jurisdiction. The court’s judgment has been described by a former President of the European Court of Human Rights as the most significant in the court’s 65-year history. I am extremely proud of what the team achieved.

‘And we have some formidable clients. During our frequent video conference calls with the Ukrainian side in the early stages of the war our clients would usually be in basements scattered across Ukraine. Sometimes they would have to move to more secure locations during the calls as sirens sounded. It was surreal. I so admired their human spirit, their resilience.

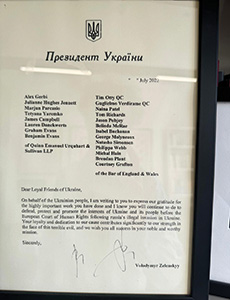

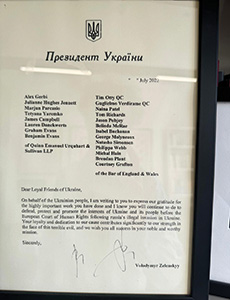

‘Since the judgment I have given each of the counsel and solicitor team a print of a Banksy mural and a first day edition of a Ukrainian postage stamp commemorating it. The mural – painted on the side of a half-destroyed building in Ukraine in the early days of the war – shows a small boy overthrowing, in judo fashion, a much bigger man resembling Vladimir Putin.’ In Otty’s room he has his own copy of this print and stamp as well as a ‘very nice’ letter of thanks to the team from President Zelenskyy.

‘The question which is often posed in relation to the case is “so what? Won’t Russia simply ignore the judgment?”

‘My answer to that is that it matters, in a world where objective truth can prove elusive, that there is a 500-page judgment from an international court recording in painstaking detail the true extent and scale of the horrors Russia has unleashed.

‘That historical record is worth something in and of itself. But more practically there are currently close to $300 billion of Russian state assets frozen in western democracies. This judgment opens another pathway – consistent with international law – to some or all of those assets being seized for Ukraine. The damage caused by Russia goes far beyond that sum.’

Otty’s father had qualified as a barrister. He never practised but had friends who did, and they first inspired his son’s interest in the law: ‘They seemed to have a varied and interesting life. I was also quite competitive as a boy and when told that law at Cambridge was the most difficult course to get into outside the sciences, I thought I would have a go. I pushed myself and was accepted for law by Trinity College.

‘While at Cambridge I was encouraged by Dad to go for mini pupillages. One I did at Brick Court must have gone well. They offered me a pupillage and scholarship which I gratefully accepted.

‘Before Bar School I travelled to India. I was very struck by the level of poverty so, while there, and instead of travelling around the country, I worked as a volunteer at Mother Teresa’s home for the dying in Calcutta. After India I decided that although I had a commercial pupillage, I wanted my practice also to embrace work with the potential for a wider societal impact.’

He was called in 1990. Brick Court did not offer him a tenancy. ‘I made a bit of a mess of a draft advice for Lord Sumption towards the end of my pupillage! But I had an excellent training and they helped me find an alternative home and most importantly this was where I first met Sir Sydney Kentridge QC, someone who became a great hero of mine and who embodied what, for me, was best about the Bar, and who showed the potential to practise across different areas of law embracing commercial work, constitutional law and human rights. Had I stayed, I might also have spent a lot of time as a junior junior on big cases, and I would have missed out on developing my advocacy.’

He went to 2 Temple Gardens and then, after 10 years, on to Twenty Essex, before coming to Blackstone in 2010. While at 2TG he undertook a three-month stage at the European Commission of Human Rights in 1993. This was the foot in the human rights door.

‘Soon afterwards I was approached by an NGO that had contacted the Bar Council: people were disappearing in South East Turkey as a result of the internal armed conflict between the Turkish army and the PKK, villages were being destroyed, reports of torture were frequent; would I help take cases for those affected to Strasbourg? I did. So, in my mid-20s, there I was, at fact-finding hearings in Turkey, cross-examining generals, prosecutors and gendarmes. In 1999 Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the PKK, was captured and sentenced to death. His Turkish lawyers wanted to internationalise the team with a view to challenging the death penalty at Strasbourg. I was asked to be involved. I said yes but also said we needed a leader. I approached Sir Sydney Kentridge. He led the case and we won. Turkey abolished its death penalty. This was the first international court to describe the death penalty as inhuman and degrading.

‘A few years later, after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, I acted in cases here and in the United States raising issues that would previously have seemed inconceivable: Did individuals held at Guantanamo Bay have any right to habeas corpus? Was it open to UK courts to admit evidence obtained by torture provided UK agents had not participated in the torture? Was it consistent with the Human Rights Convention to confine someone to their home for 18 hours a day on the basis of asserted suspicion, the grounds for which were not disclosed?’

Otty had by then moved to Twenty Essex, spending three years on the Attorney General’s A Panel before taking silk in 2006.

It’s by no means all human rights though.

‘The biggest advantage of the Bar is variety and excitement. I do anything with an international dimension before domestic and international courts as well as significant amounts of investment treaty, sanctions, sports and public law work.’

In November, his appointment was announced to the Attorney General’s new Senior Treasury Counsel Group, providing strategic advice on the government’s most significant litigation. In recent years he has acted for clients as varied as Princess Haya of Jordan, the former King of Spain, the former Prime Minister of Kazakhstan, the owner of the Ritz, Google, Apple, Mastercard, World Athletics and Leicester City as well as HMG and a wide range of foreign governments.

Where does he stand in the current debates about the European Convention on Human Rights? ‘The core principles of the Convention are vitally important. I think it would be a profound mistake to leave the Convention system. Strasbourg is not perfect – few institutions are – but it deserves the support of major democracies. And as the Ukraine case shows it does some hugely important work. If reform or reinterpretation is needed it is much better for UK lawyers and judges to be shaping this landscape than for us to walk out, particularly at a time when the rules based international order which the UK helped construct is under such pressure.

‘For now, I am interested in what the law can do to protect really fundamental rights and in winning cases where it matters. An example is protecting minority rights. In 2010 I was asked to write an opinion for the Commonwealth Lawyers Association addressing very draconian anti-gay legislation in Uganda. It wasn’t a difficult opinion to write as the law breached international and constitutional law in a host of respects, but what struck me was how widespread similar legislation was. I decided to set up an NGO – the Human Dignity Trust – to support challenges to these laws. I wanted us to be the sensible, calm voice in the room.

‘Since 2010 we have supported local activists bringing cases across the Commonwealth seeking to strike down laws of this kind as unconstitutional and inconsistent with basic rights to privacy, dignity and equality. When we started 43 Commonwealth countries criminalised same-sex relations. It’s now 29. Millions of people who previously lived under the threat of prosecution and state sanctioned prejudice no longer do so. That work continues.’

Life outside the law? ‘When I was in my 20s my wife and I set up the Alphabet bar in Beak Street, Soho with some school and college friends. Virgin Radio moved next door, and David Bowie was one of our early customers. That did wonders for us. Time Out named us as the Best Bar in London. We sold it later – to my regret!’

Otty and his Italian wife are the proud parents of two daughters: ‘All three of them delight and challenge me every day!’ Photographs of Otty’s family adorn his room.

Another exhibit in the room is a photograph of Otty with Eliud Kipchoge, the double Olympic marathon champion. ‘I met him on one of my running trips in Kenya. In my mid-thirties, never having run more than half an hour before, I discovered to my surprise that I was a genuinely talented distance runner. I ran the New York marathon for charity.’ He continued his charity marathons. ‘I run to Chambers and back every day. I can still run a marathon in under three hours, and a half-marathon in about one hour twenty.’ These times make him in the jargon ‘competitive’.

Advice to others? ‘Try and bring the same intellectual rigour and clarity to every case. Enjoy the “ups” because there will certainly be some “downs”. And try to be useful and do some good along the way.’

‘On 24 February 2022 Russia invaded Ukraine. Within a week, and having acted for Ukraine before, I was asked if, together with Quinn Emmanuel [QE], I would lead a case for Ukraine against Russia in the European Court of Human Rights seeking to establish full accountability for the war. And would I do it pro bono?

‘I said yes as it seemed the right thing to do. Together with Lord Verdirame KC I put together a team of 11 brilliant juniors from Blackstone and Twenty Essex, working together with the QE team. We filed the first round of submissions in the case within months of the war starting and went from there.’

Tim Otty KC of Blackstone Chambers, Barrister of the Year 2023, is talking about the beginning of Ukraine and the Netherlands v Russia. Following a hearing in June 2024, in July of this year the Grand Chamber delivered its judgment. Russia was found accountable for systematic and flagrant violations across Ukraine, violations including indiscriminate military attacks, summary execution of civilians, torture including the use of rape as a weapon of war, arbitrary detentions and property damage on a massive, unprecedented scale.

Back to the start. ‘In March 2022 the first challenge was to capture in real time the sheer scale of what was happening. We had different members of the legal team working across the world 24 hours a day to build a master chronology to record every reported incident as it occurred.

‘The biggest challenge legally was to show that all victims of Russia’s attacks were within its jurisdiction for Convention purposes even in territory not occupied by Russia.

‘Would it be possible to hold Russia to account for bombing and missile attacks across the country as well as for the atrocities in Bucha and elsewhere?

‘And to win this argument we would need to persuade the Grand Chamber to overrule or distinguish a line of case law going back to the early 2000s.

‘We argued that all victims of Russian attacks, wherever they were, had to be held to be within Russian jurisdiction and sought to emphasise that this was the first instance of full-scale war in Europe since 1945, and that Russia’s attempt to eliminate a sovereign state through its attacks made this a case apart.

‘In an endeavour to give the court comfort in taking this new course we sought to get other state signatories to intervene in the proceedings in our support. Twenty-six did. Our argument carried the day.

‘The case was clear cut on the merits but by no means so on jurisdiction. The court’s judgment has been described by a former President of the European Court of Human Rights as the most significant in the court’s 65-year history. I am extremely proud of what the team achieved.

‘And we have some formidable clients. During our frequent video conference calls with the Ukrainian side in the early stages of the war our clients would usually be in basements scattered across Ukraine. Sometimes they would have to move to more secure locations during the calls as sirens sounded. It was surreal. I so admired their human spirit, their resilience.

‘Since the judgment I have given each of the counsel and solicitor team a print of a Banksy mural and a first day edition of a Ukrainian postage stamp commemorating it. The mural – painted on the side of a half-destroyed building in Ukraine in the early days of the war – shows a small boy overthrowing, in judo fashion, a much bigger man resembling Vladimir Putin.’ In Otty’s room he has his own copy of this print and stamp as well as a ‘very nice’ letter of thanks to the team from President Zelenskyy.

‘The question which is often posed in relation to the case is “so what? Won’t Russia simply ignore the judgment?”

‘My answer to that is that it matters, in a world where objective truth can prove elusive, that there is a 500-page judgment from an international court recording in painstaking detail the true extent and scale of the horrors Russia has unleashed.

‘That historical record is worth something in and of itself. But more practically there are currently close to $300 billion of Russian state assets frozen in western democracies. This judgment opens another pathway – consistent with international law – to some or all of those assets being seized for Ukraine. The damage caused by Russia goes far beyond that sum.’

Otty’s father had qualified as a barrister. He never practised but had friends who did, and they first inspired his son’s interest in the law: ‘They seemed to have a varied and interesting life. I was also quite competitive as a boy and when told that law at Cambridge was the most difficult course to get into outside the sciences, I thought I would have a go. I pushed myself and was accepted for law by Trinity College.

‘While at Cambridge I was encouraged by Dad to go for mini pupillages. One I did at Brick Court must have gone well. They offered me a pupillage and scholarship which I gratefully accepted.

‘Before Bar School I travelled to India. I was very struck by the level of poverty so, while there, and instead of travelling around the country, I worked as a volunteer at Mother Teresa’s home for the dying in Calcutta. After India I decided that although I had a commercial pupillage, I wanted my practice also to embrace work with the potential for a wider societal impact.’

He was called in 1990. Brick Court did not offer him a tenancy. ‘I made a bit of a mess of a draft advice for Lord Sumption towards the end of my pupillage! But I had an excellent training and they helped me find an alternative home and most importantly this was where I first met Sir Sydney Kentridge QC, someone who became a great hero of mine and who embodied what, for me, was best about the Bar, and who showed the potential to practise across different areas of law embracing commercial work, constitutional law and human rights. Had I stayed, I might also have spent a lot of time as a junior junior on big cases, and I would have missed out on developing my advocacy.’

He went to 2 Temple Gardens and then, after 10 years, on to Twenty Essex, before coming to Blackstone in 2010. While at 2TG he undertook a three-month stage at the European Commission of Human Rights in 1993. This was the foot in the human rights door.

‘Soon afterwards I was approached by an NGO that had contacted the Bar Council: people were disappearing in South East Turkey as a result of the internal armed conflict between the Turkish army and the PKK, villages were being destroyed, reports of torture were frequent; would I help take cases for those affected to Strasbourg? I did. So, in my mid-20s, there I was, at fact-finding hearings in Turkey, cross-examining generals, prosecutors and gendarmes. In 1999 Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the PKK, was captured and sentenced to death. His Turkish lawyers wanted to internationalise the team with a view to challenging the death penalty at Strasbourg. I was asked to be involved. I said yes but also said we needed a leader. I approached Sir Sydney Kentridge. He led the case and we won. Turkey abolished its death penalty. This was the first international court to describe the death penalty as inhuman and degrading.

‘A few years later, after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, I acted in cases here and in the United States raising issues that would previously have seemed inconceivable: Did individuals held at Guantanamo Bay have any right to habeas corpus? Was it open to UK courts to admit evidence obtained by torture provided UK agents had not participated in the torture? Was it consistent with the Human Rights Convention to confine someone to their home for 18 hours a day on the basis of asserted suspicion, the grounds for which were not disclosed?’

Otty had by then moved to Twenty Essex, spending three years on the Attorney General’s A Panel before taking silk in 2006.

It’s by no means all human rights though.

‘The biggest advantage of the Bar is variety and excitement. I do anything with an international dimension before domestic and international courts as well as significant amounts of investment treaty, sanctions, sports and public law work.’

In November, his appointment was announced to the Attorney General’s new Senior Treasury Counsel Group, providing strategic advice on the government’s most significant litigation. In recent years he has acted for clients as varied as Princess Haya of Jordan, the former King of Spain, the former Prime Minister of Kazakhstan, the owner of the Ritz, Google, Apple, Mastercard, World Athletics and Leicester City as well as HMG and a wide range of foreign governments.

Where does he stand in the current debates about the European Convention on Human Rights? ‘The core principles of the Convention are vitally important. I think it would be a profound mistake to leave the Convention system. Strasbourg is not perfect – few institutions are – but it deserves the support of major democracies. And as the Ukraine case shows it does some hugely important work. If reform or reinterpretation is needed it is much better for UK lawyers and judges to be shaping this landscape than for us to walk out, particularly at a time when the rules based international order which the UK helped construct is under such pressure.

‘For now, I am interested in what the law can do to protect really fundamental rights and in winning cases where it matters. An example is protecting minority rights. In 2010 I was asked to write an opinion for the Commonwealth Lawyers Association addressing very draconian anti-gay legislation in Uganda. It wasn’t a difficult opinion to write as the law breached international and constitutional law in a host of respects, but what struck me was how widespread similar legislation was. I decided to set up an NGO – the Human Dignity Trust – to support challenges to these laws. I wanted us to be the sensible, calm voice in the room.

‘Since 2010 we have supported local activists bringing cases across the Commonwealth seeking to strike down laws of this kind as unconstitutional and inconsistent with basic rights to privacy, dignity and equality. When we started 43 Commonwealth countries criminalised same-sex relations. It’s now 29. Millions of people who previously lived under the threat of prosecution and state sanctioned prejudice no longer do so. That work continues.’

Life outside the law? ‘When I was in my 20s my wife and I set up the Alphabet bar in Beak Street, Soho with some school and college friends. Virgin Radio moved next door, and David Bowie was one of our early customers. That did wonders for us. Time Out named us as the Best Bar in London. We sold it later – to my regret!’

Otty and his Italian wife are the proud parents of two daughters: ‘All three of them delight and challenge me every day!’ Photographs of Otty’s family adorn his room.

Another exhibit in the room is a photograph of Otty with Eliud Kipchoge, the double Olympic marathon champion. ‘I met him on one of my running trips in Kenya. In my mid-thirties, never having run more than half an hour before, I discovered to my surprise that I was a genuinely talented distance runner. I ran the New York marathon for charity.’ He continued his charity marathons. ‘I run to Chambers and back every day. I can still run a marathon in under three hours, and a half-marathon in about one hour twenty.’ These times make him in the jargon ‘competitive’.

Advice to others? ‘Try and bring the same intellectual rigour and clarity to every case. Enjoy the “ups” because there will certainly be some “downs”. And try to be useful and do some good along the way.’

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar