*/

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

In the December issue of Counsel I outlined the new system of Making Tax Digital for Income Tax (‘MTD for IT’) and sought to place the system in a wider context. This follow-up article seeks to address the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system.

The key points are:

Mr B has been a barrister in self-employed practice for a number of years, preparing accounts to 5 April. For the years up to 5 April 2024, apart from his first seven years in practice, he prepared his tax return on an accounts basis, as he was required to do by law.

Mr B’s practice lies mainly in the field of civil damages. It takes on average six months to collect fees. Using the accounts basis the closing debtors figure increases profits and so tax liabilities. Tax has to be paid in cash, so Mr B sometimes borrows against his debtors figure to fund tax and living expenses (aged debt funding).

Mr B’s practice includes catastrophic personal injury cases. These are funded by insurance companies and take many years to settle and before any payment becomes billable. He is required therefore to bring in work in progress.

Work in progress records the fair value of work he has performed in the year but which has not been completed or become billable. The fair value will include costs which he has incurred to earn the right to consideration.

He does some cases on a ‘no win, no fee’ basis, which is only recognised as income on a successful outcome.

He also does some ‘pay at end’ work, in respect of which a fee is only recognised when agreed.

Of his cash income, 15% is taken up by chambers expenses.

He uses a room in his home as an office, working there for 60 hours each month. He chooses to use the fixed rate deduction scheme (Income Tax (Trading and Other Income) Act 2025 (ITTOIA), s 94H) to calculate allowable expenditure for use of home for business purposes.

In 2024/25 he spent £3,000 on office equipment, including a desk and new computer.

With the help of his accountants, Mr B is now looking at three connected issues:

In approaching these issues, he understands that:

Mr B used the default accruals basis in 2023/24. If he changes to the default cash basis in 2024/25 he will calculate his profits on the basis of receipts less expenses for the period in question.

The change of accounting basis will have a knock-on effect for the calculation of his profits from 2024/25 because:

Where there is a change from one accounting basis to another, ITTOIA ss 227-240 look at the period immediately before the change in policy and the period immediately after the change in policy to ensure that no receipts or expenses fall out of account or are counted twice as a result of the transition. If there are any such amounts these are adjusted for in the first period of account under the new accounting basis. Ther standard accounting and tax procedure for change of accounting basis is set out in ITTOIA, s 231. This refers to the ‘old basis’ (Year 1) and the ‘new basis’ (Year 2).

A single adjustment is calculated bringing all such amounts together as ‘adjustment income’ (ITTOIA, s 231) or an ‘adjustment expense’ (ITTOIA, s 233).

Adjustment income can be spread forward over six years (ITTOIA, s 232). An adjustment expense is treated as incurred on the last day of the accounting period in which the new basis is adopted (s 233).

A change from cash basis to accounts basis will usually produce adjustment income.

A change from accounts basis to cash basis will usually produce adjustment expense.

Purchase of fixed assets (such as computers) will not alter the taxable income, as annual investment allowance (AIA) is likely to cover any expenditure, but one would need to keep track of a nil balance on the pool in the event of any future disposal.

These adjustments to his 2023/2024 profits will produce additional income or additional expenses in 2024/25. They are not recognised as separate items, but incorporated into a composite figure.

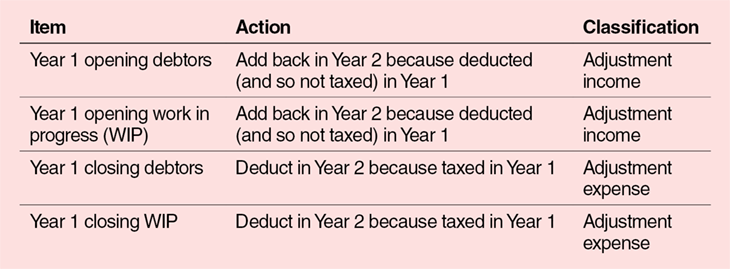

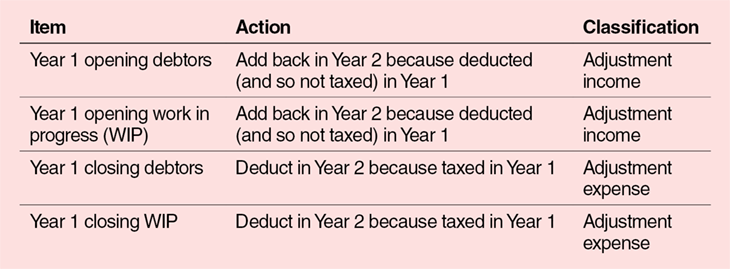

Where the old basis (Year 1) is accounts basis and the new basis (Year 2) is cash basis the main adjustments are as follows:

Adjustment income increases Mr B’s profits in 2024/25 because it accelerates profit recognition.

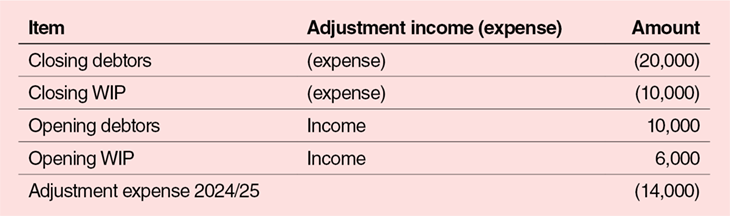

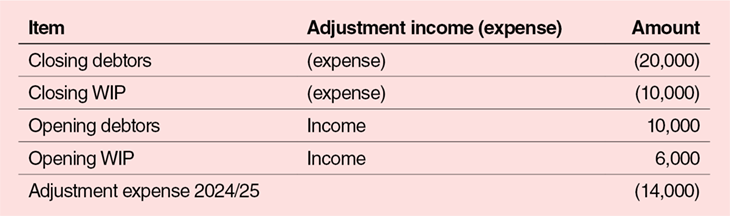

Adjustment – Mr B’s 2023/24 figures show:

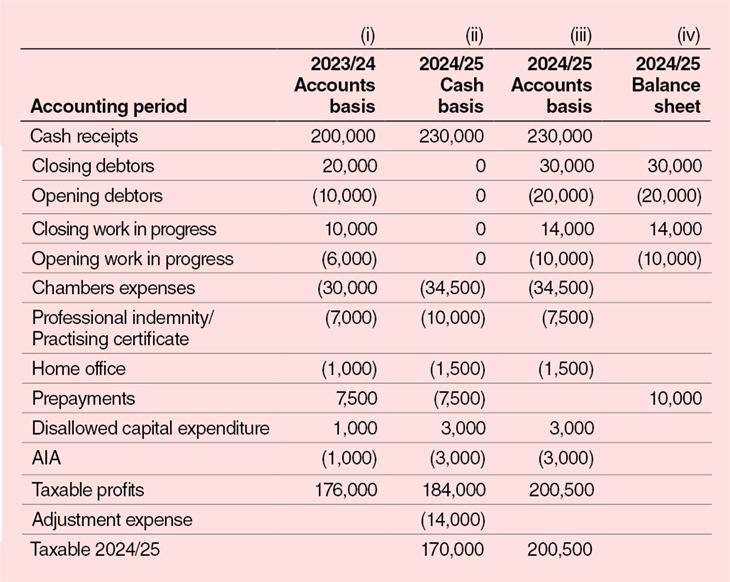

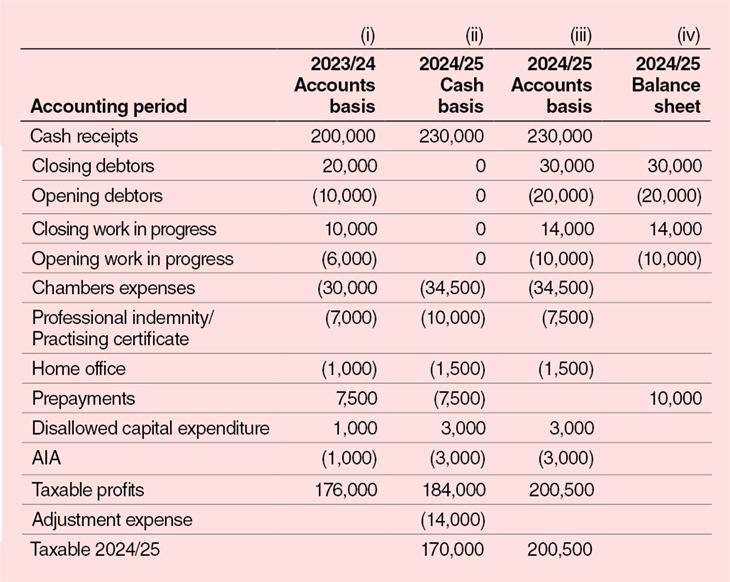

With this information, Mr B can see what his profits are likely to be for 2024/25 on a cash basis, and on an accounts basis. The table below shows:

i. His profits for 2023/24 (accounts basis).

ii. His profits for 2024/25 (cash basis).

iii. His profits for 2024/25 (accounts basis).

iv. Closing balance sheet entries 5 April 2025 (accounts basis).

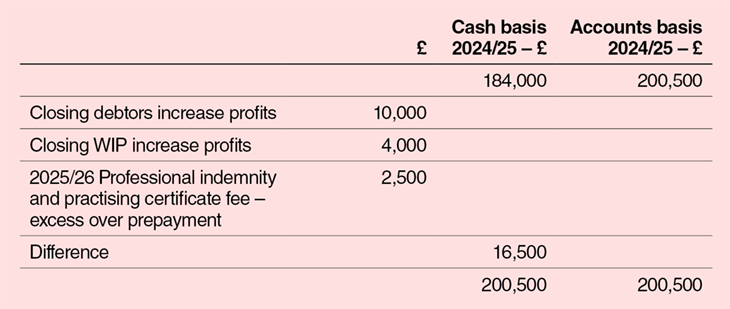

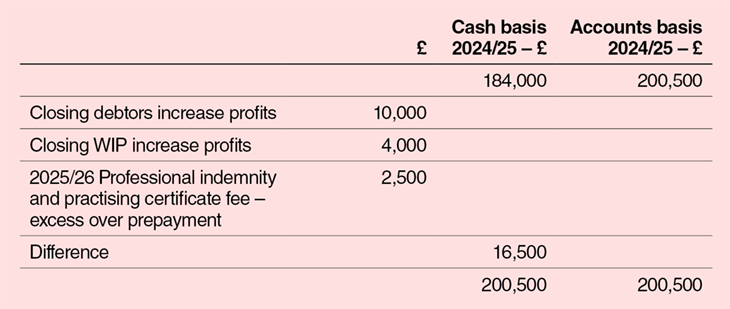

Reconciliation of (ii) and (iii):

As one would expect, the cash profits for 2024/25 are lower than the accounts profits because the net increase in debtors and work in progress does not have to be included in the 2024/25 profits.

The effect is magnified by the adjustment expense.

If he adopted the cash basis for 2024/25, Mr B would have a lower tax bill for that year.

On the other hand, his earnings would be lower for borrowing and annual pension allowance purposes.

As regards MTD for IT the advantages of the cash basis are striking. If he arranges for all his receipts and all his expenses to go through one bank account, those figures can be automatically transmitted to his accountants who can then automatically transmit them to HMRC for his quarterly updates. The figures entered into his fourth quarterly update will be very close to the end of year figures which will go into his ITSA for 2025/26.

If he opts for the accruals basis, either the figures in the quarterly updates will be remote from the actual profits figures for the year, or the quarterly update figures actual will be remote from cash income and expenditure.

It seems to me highly likely that once the new system of quarterly updates is bedded down, quarterly updates are going to have to be accompanied by quarterly payments – as already happens with VAT. HMRC will require a direct debit authority to collect the quarterly payments – as with VAT. Quarterly payments will be advance instalments of the overall tax liability for the year, accounted for on a pay-as-you-go basis. Thus the closer the correspondence between quarterly updates and annual tax liability the more the annual tax return will fade into insignificance.

This is speculation and lies in the future.

The new system will undoubtedly produce greater operational efficiencies, improve Treasury cash flows and allow short-term government borrowing to be reduced. But efficiency should not be the sole object of a political and fiscal system. I have spent long enough as the employee of large organisations to be aware that when changes are promulgated in the name of greater efficiency, it is likely that one is being sold a pup. For dinosaurs of the tax system, such as myself, this is all the crack of doom. But my ilk will be consigned to the dustbin of history, as Trotsky observed of the Russian Mensheviks.

Each barrister’s circumstances are individual. Too much should not be read into one set of hypothetical figures. However, there is much to ponder before 31 January 2026 and the time for action is limited.

Part 3, looking at the range of new software products on offer to implement MTD for IT, will appear in a future issue. ‘Making Tax Digital – for barristers (1)’ can be read here.

In the December issue of Counsel I outlined the new system of Making Tax Digital for Income Tax (‘MTD for IT’) and sought to place the system in a wider context. This follow-up article seeks to address the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system.

The key points are:

Mr B has been a barrister in self-employed practice for a number of years, preparing accounts to 5 April. For the years up to 5 April 2024, apart from his first seven years in practice, he prepared his tax return on an accounts basis, as he was required to do by law.

Mr B’s practice lies mainly in the field of civil damages. It takes on average six months to collect fees. Using the accounts basis the closing debtors figure increases profits and so tax liabilities. Tax has to be paid in cash, so Mr B sometimes borrows against his debtors figure to fund tax and living expenses (aged debt funding).

Mr B’s practice includes catastrophic personal injury cases. These are funded by insurance companies and take many years to settle and before any payment becomes billable. He is required therefore to bring in work in progress.

Work in progress records the fair value of work he has performed in the year but which has not been completed or become billable. The fair value will include costs which he has incurred to earn the right to consideration.

He does some cases on a ‘no win, no fee’ basis, which is only recognised as income on a successful outcome.

He also does some ‘pay at end’ work, in respect of which a fee is only recognised when agreed.

Of his cash income, 15% is taken up by chambers expenses.

He uses a room in his home as an office, working there for 60 hours each month. He chooses to use the fixed rate deduction scheme (Income Tax (Trading and Other Income) Act 2025 (ITTOIA), s 94H) to calculate allowable expenditure for use of home for business purposes.

In 2024/25 he spent £3,000 on office equipment, including a desk and new computer.

With the help of his accountants, Mr B is now looking at three connected issues:

In approaching these issues, he understands that:

Mr B used the default accruals basis in 2023/24. If he changes to the default cash basis in 2024/25 he will calculate his profits on the basis of receipts less expenses for the period in question.

The change of accounting basis will have a knock-on effect for the calculation of his profits from 2024/25 because:

Where there is a change from one accounting basis to another, ITTOIA ss 227-240 look at the period immediately before the change in policy and the period immediately after the change in policy to ensure that no receipts or expenses fall out of account or are counted twice as a result of the transition. If there are any such amounts these are adjusted for in the first period of account under the new accounting basis. Ther standard accounting and tax procedure for change of accounting basis is set out in ITTOIA, s 231. This refers to the ‘old basis’ (Year 1) and the ‘new basis’ (Year 2).

A single adjustment is calculated bringing all such amounts together as ‘adjustment income’ (ITTOIA, s 231) or an ‘adjustment expense’ (ITTOIA, s 233).

Adjustment income can be spread forward over six years (ITTOIA, s 232). An adjustment expense is treated as incurred on the last day of the accounting period in which the new basis is adopted (s 233).

A change from cash basis to accounts basis will usually produce adjustment income.

A change from accounts basis to cash basis will usually produce adjustment expense.

Purchase of fixed assets (such as computers) will not alter the taxable income, as annual investment allowance (AIA) is likely to cover any expenditure, but one would need to keep track of a nil balance on the pool in the event of any future disposal.

These adjustments to his 2023/2024 profits will produce additional income or additional expenses in 2024/25. They are not recognised as separate items, but incorporated into a composite figure.

Where the old basis (Year 1) is accounts basis and the new basis (Year 2) is cash basis the main adjustments are as follows:

Adjustment income increases Mr B’s profits in 2024/25 because it accelerates profit recognition.

Adjustment – Mr B’s 2023/24 figures show:

With this information, Mr B can see what his profits are likely to be for 2024/25 on a cash basis, and on an accounts basis. The table below shows:

i. His profits for 2023/24 (accounts basis).

ii. His profits for 2024/25 (cash basis).

iii. His profits for 2024/25 (accounts basis).

iv. Closing balance sheet entries 5 April 2025 (accounts basis).

Reconciliation of (ii) and (iii):

As one would expect, the cash profits for 2024/25 are lower than the accounts profits because the net increase in debtors and work in progress does not have to be included in the 2024/25 profits.

The effect is magnified by the adjustment expense.

If he adopted the cash basis for 2024/25, Mr B would have a lower tax bill for that year.

On the other hand, his earnings would be lower for borrowing and annual pension allowance purposes.

As regards MTD for IT the advantages of the cash basis are striking. If he arranges for all his receipts and all his expenses to go through one bank account, those figures can be automatically transmitted to his accountants who can then automatically transmit them to HMRC for his quarterly updates. The figures entered into his fourth quarterly update will be very close to the end of year figures which will go into his ITSA for 2025/26.

If he opts for the accruals basis, either the figures in the quarterly updates will be remote from the actual profits figures for the year, or the quarterly update figures actual will be remote from cash income and expenditure.

It seems to me highly likely that once the new system of quarterly updates is bedded down, quarterly updates are going to have to be accompanied by quarterly payments – as already happens with VAT. HMRC will require a direct debit authority to collect the quarterly payments – as with VAT. Quarterly payments will be advance instalments of the overall tax liability for the year, accounted for on a pay-as-you-go basis. Thus the closer the correspondence between quarterly updates and annual tax liability the more the annual tax return will fade into insignificance.

This is speculation and lies in the future.

The new system will undoubtedly produce greater operational efficiencies, improve Treasury cash flows and allow short-term government borrowing to be reduced. But efficiency should not be the sole object of a political and fiscal system. I have spent long enough as the employee of large organisations to be aware that when changes are promulgated in the name of greater efficiency, it is likely that one is being sold a pup. For dinosaurs of the tax system, such as myself, this is all the crack of doom. But my ilk will be consigned to the dustbin of history, as Trotsky observed of the Russian Mensheviks.

Each barrister’s circumstances are individual. Too much should not be read into one set of hypothetical figures. However, there is much to ponder before 31 January 2026 and the time for action is limited.

Part 3, looking at the range of new software products on offer to implement MTD for IT, will appear in a future issue. ‘Making Tax Digital – for barristers (1)’ can be read here.

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar