*/

In 1985, a time in Britain described by one of the artists in this exhibition as a grey landscape where ginger and garlic were hard to come by, 11 Black women artists came to together in Lubaina Himid’s groundbreaking show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), The Thin Black Line. The original exhibition emerged from the early 1980s British Black Arts Movement, when a generation of young Black and Asian women artists demanded space in galleries that had systematically excluded them. Himid’s vision as a curator positioned their works at the centre of critical debates about race, gender and artistic practice and the show established these artists as essential contributors to British cultural discourse. Exhibition participant Sonia Boyce described the show as ‘bold’ as Black women artists ‘were stridently making our presence apparent in the arts’ and bold ‘conceptually and stylistically’.

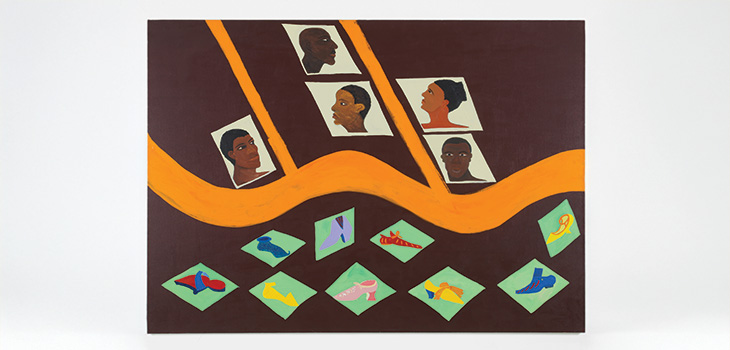

Moving forwards 40 years, this 2025 iteration of the show, again at the ICA, demonstrates how artistic networks sustain and transform over time. This is not a nostalgic retrospective and Himid presents a dynamic conversation between past and present. For example, mixed-media artist Chila Kumari Burman’s new neon works dazzle the ICA’s concourse with a blend of pop imagery and symbolism which explores her cultural identity, while Marlene Smith’s sculpture, inspired by family photographs of her Windrush parents, reflect the exhibition notes that in the present day, ‘bigotry has been emboldened’. These new commissions sit alongside works spanning four decades, from Sonia Boyce’s early Rice n Peas (1982) to Veronica Ryan’s recent hanging crochet sculpture Threads (2024).

The exhibition reveals the interconnected nature of these artistic practices. Claudette Johnson’s Trilogy series, depicting Black female sitters including fellow exhibition participants Brenda Agard and Ingrid Pollard (asking her subject to ‘stand in a way that allowed her to occupy as much space as possible’), shows how these artists became both creators and subjects within each other’s work. This extends to Himid’s personal collection, which features works by Boyce, Pollard and Maud Sulter, illustrating the bonds forged through shared struggle and mutual support.

The exhibition links artistic practice to broader questions of British identity and belonging. Ingrid Pollard’s landscape photography explores constructions of Britishness and racial difference, while Sutapa Biswas’s photographs from her 2021 Lumen series continues her exploration of colonial history and its impact on individuals. Jennifer Comrie’s pastel drawings bridge figurative art and abstraction, embodying what she describes as ‘the cry within her and the Black community’.

Contemporaneous correspondence displayed in the exhibition reveals the institutional barriers faced when the 1985 exhibition was first conceived, providing an insight into the mechanics of cultural change. Himid, however, notes that many Black women artists remained ‘quite invisible’ over the following decades, that ‘progress took so long to bear fruit’ and those with the power to advance exposure for them, often failed to do so.

This thoughtful exhibition succeeds in demonstrating how The Thin Black Line artists attempted to transform British visual culture and to provide a ladder for subsequent generations while continuing to produce vital and challenging work. The accompanying programme of films, talks and performances fulfils Himid’s original ambition for a multi-disciplinary Black arts festival.

Most significantly, Connecting Thin Black Lines reveals how groups of artists can sustain themselves across decades and how the fight for representation remains as urgent today as it was 40 years ago.

In 1985, a time in Britain described by one of the artists in this exhibition as a grey landscape where ginger and garlic were hard to come by, 11 Black women artists came to together in Lubaina Himid’s groundbreaking show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), The Thin Black Line. The original exhibition emerged from the early 1980s British Black Arts Movement, when a generation of young Black and Asian women artists demanded space in galleries that had systematically excluded them. Himid’s vision as a curator positioned their works at the centre of critical debates about race, gender and artistic practice and the show established these artists as essential contributors to British cultural discourse. Exhibition participant Sonia Boyce described the show as ‘bold’ as Black women artists ‘were stridently making our presence apparent in the arts’ and bold ‘conceptually and stylistically’.

Moving forwards 40 years, this 2025 iteration of the show, again at the ICA, demonstrates how artistic networks sustain and transform over time. This is not a nostalgic retrospective and Himid presents a dynamic conversation between past and present. For example, mixed-media artist Chila Kumari Burman’s new neon works dazzle the ICA’s concourse with a blend of pop imagery and symbolism which explores her cultural identity, while Marlene Smith’s sculpture, inspired by family photographs of her Windrush parents, reflect the exhibition notes that in the present day, ‘bigotry has been emboldened’. These new commissions sit alongside works spanning four decades, from Sonia Boyce’s early Rice n Peas (1982) to Veronica Ryan’s recent hanging crochet sculpture Threads (2024).

The exhibition reveals the interconnected nature of these artistic practices. Claudette Johnson’s Trilogy series, depicting Black female sitters including fellow exhibition participants Brenda Agard and Ingrid Pollard (asking her subject to ‘stand in a way that allowed her to occupy as much space as possible’), shows how these artists became both creators and subjects within each other’s work. This extends to Himid’s personal collection, which features works by Boyce, Pollard and Maud Sulter, illustrating the bonds forged through shared struggle and mutual support.

The exhibition links artistic practice to broader questions of British identity and belonging. Ingrid Pollard’s landscape photography explores constructions of Britishness and racial difference, while Sutapa Biswas’s photographs from her 2021 Lumen series continues her exploration of colonial history and its impact on individuals. Jennifer Comrie’s pastel drawings bridge figurative art and abstraction, embodying what she describes as ‘the cry within her and the Black community’.

Contemporaneous correspondence displayed in the exhibition reveals the institutional barriers faced when the 1985 exhibition was first conceived, providing an insight into the mechanics of cultural change. Himid, however, notes that many Black women artists remained ‘quite invisible’ over the following decades, that ‘progress took so long to bear fruit’ and those with the power to advance exposure for them, often failed to do so.

This thoughtful exhibition succeeds in demonstrating how The Thin Black Line artists attempted to transform British visual culture and to provide a ladder for subsequent generations while continuing to produce vital and challenging work. The accompanying programme of films, talks and performances fulfils Himid’s original ambition for a multi-disciplinary Black arts festival.

Most significantly, Connecting Thin Black Lines reveals how groups of artists can sustain themselves across decades and how the fight for representation remains as urgent today as it was 40 years ago.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar

Jury-less trial proposals threaten fairness, legitimacy and democracy without ending the backlog, writes Professor Cheryl Thomas KC (Hon), the UK’s leading expert on juries, judges and courts