*/

Almost half of women at the Bar have encountered discrimination and over two-thirds have considered leaving. David Wurtzel analyses the survey findings

We want the Bar to reflect the society it serves.

Although we are still a long way from a Bar which is gender equal, we want a Bar in which men and women, white and BAME (black and minority ethnic) barristers are treated equally. In some respects this does not happen. Women barristers still suffer harassment and/or discrimination at the hands of male barristers and clerks. Because of the perceived impact on their practices, overwhelmingly the women do not report it. We have known this as a statistical fact at least since the comprehensive reports Barristers Working Lives in 2011 and 2013. In 2014 the Bar Council commissioned the report Snapshot: The Experience of Self-Employed Women at the Bar. Seventy-three women, most of whom were over 15 years’ Call, recorded their experiences and concerns in focus groups. It was emphasised that most if not all of the examples cited of inappropriate behaviour ’were in the past’ and reports of recent sexual harassment were ’rare’.

A fuller and more accurate picture has emerged from the research published in July by the Bar Standards Board (Women at the Bar). The starting point was the 2012 Equality Rules which reflect the legislation which applies to the employed but not to the self-employed Bar. Have the Rules been adhered to, were barristers aware of whether their chambers had implemented them, were they satisfied with them, and had they made a difference? An online survey was sent to all women barristers: 1,333, 23% of the total, replied. Although self-selecting, the respondents in fact reflected the actual range of seniority and age of women barristers. Some employed barristers, in any event protected by statutory rights, also replied.

Recruitment

Chambers are obliged to ensure that recruitment and selection processes use objective and fair criteria. The BSB requires every member of a selection panel to be trained in fair recruitment and selection processes. Eighty per cent of self-employed respondents (but 65.6% of employed barristers) agreed that recruitment was fair, and most said that their panel members had undergone the training.

Work allocation

The Equality Rules require chambers to review the allocation of unassigned work regularly, collecting and analysing data broken down by race, disability and gender, and taking appropriate remedial action in respect of disparities in the data. The majority of respondents (52.2%) did not know whether their chambers did this or not, the highest figure being for those under five years’ Call, who might be thought to be most affected. 71.6% of respondents said that they had not queried how work had been allocated to them; again, it was those under five years’ Call who were in the higher numbers here. About half of those who did query what was going on felt that there was an improvement after that while the other half did not receive a suitable explanation or found that things changed for the worse. Some pointed out problems, such as, if clerks were trying to steer solicitors towards a particular barrister, the work did not count as ’unassigned’. Over a quarter had negative experiences, a lack of transparency being often cited, but a third had positive things to say about how the clerks made every effort to keep everyone employed to the extent that they wanted to be.

Working flexibly

Under the Equality Rules, chambers are required to have a flexible working policy which covers the rights of tenants to take a career break, to work part time, flexible hours or from home, and also a detailed maternity/paternity leave policy.

Of self-employed respondents, 58.4% said their chambers had a flexible working policy; 10.2% said that theirs did not. 58% thought their policy was excellent or good; only 6.6% thought it poor or very poor. Of those who had requested flexible working, 64.4% did so because of caring responsibilities for children. Of those who had applied, 85% had their request granted. Some of those, however, did not always get a rent rebate which would have made it financially practical. Of those who did not do flexible working, the most common concerns were the impact on income, the demands of courtroom practice and the issue of fixed chambers expenses.

Some 73% of self-employed respondents agreed that flexible working had helped them to remain at the Bar but only 25.6% agreed that it had supported their progression at the Bar. Over 60% cited negative impacts on their practice or progression, the most common impact being the quality or quantity of work they received; 10% highlighted negative attitudes towards flexible working from chambers, clients or clerks.

As for a maternity/paternity leave policy, a majority felt that their leave policy was good or excellent though this varied dramatically depending on whether chambers had consulted on it. How well had chambers supported those who took leave? 53.7% thought that support before leave was good or excellent but only 44% so rated support during leave and 47.8% so rated it after leave when 28.5% rated it poor or very poor.

Although a majority (53.6%) felt that being able to take this leave had helped them to stay at the Bar, 70% noted a sometimes significant negative impact on their practice or progression, with loss of clients and contacts and financial issues (such as fixed chambers rent) which caused some to return earlier than planned. Some reported that they were now considered to be less committed to the Bar and were assumed to be the secondary earner in the family.

Harassment

Remarkably only 48% of self-employed barrister respondents knew whether chambers had a harassment policy or not but the majority of those who did know thought it was good or excellent. Policy or not, 40% of the respondents said that they had experienced harassment at the Bar but this differed according to ethnicity: 48% of BAME respondents replied ’Yes’ compared to 38.4% of white women. Half of those who experienced it said that it came from members of chambers including their pupil supervisor or the clerks; the other half said it came from other barristers, judges or solicitors. Overall over half experienced it during pupillage. It appears to have been more prevalent in the past – 48.7% of women over 20 years Call or over had experienced it – but under 15 years’ Call the percentage of those who had experienced it was very much the same including 34.4% of those under five years’ Call. 43% of those who experienced it had done so after the 2012 Rules had been introduced. Sadly harassment is not ’rare’ and it is still happening.

80.3% had not reported it. Of these 40% cited ’harming career prospects’ as the reason – gaining a tenancy, obtaining work, being known as a troublemaker– and a quarter cited cultural attitudes of the Bar towards harassment (‘an occupational hazard’) or the reporting of it. A quarter felt it had not been serious enough to report, and they were able to deal with it informally. Those who had reported it split equally between those who were satisfied with the response and those who were not.

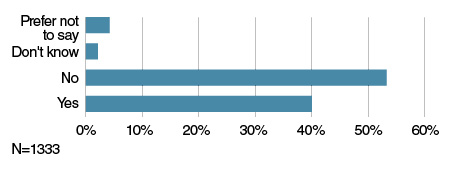

Have you ever experienced harassment at the Bar?

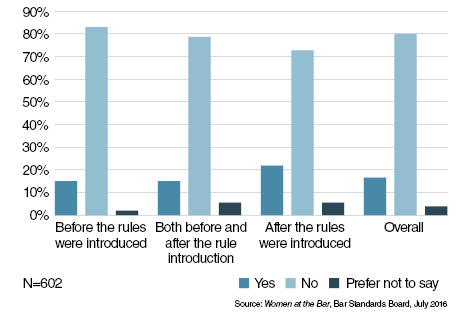

Did you report the harassment you experienced?

Discrimination

In contrast to the questions about harassment, more women (45% of respondents) stated that they had experienced discrimination than those who stated that they had not (35.6%). Higher ‘Yes‘ responses came from those who were primary carers for their children (48.6%) and from BAME barristers, 54.2% of whom stated that they had experienced discrimination. A majority of those who experienced it had done so even after the Rules were introduced but overall the figures vary considerably depending on seniority: 56.4% of women over 20 years‘ Call had experienced it compared to 40.2% of those of five to nine years‘ Call and 32.8% for women under five years‘ Call. Some 60% said it came from within chambers or their organisation; over half stated that it related to the behaviour of their clerks and/or the allocation of work.

Once more there was a high figure for non-reporting (78.4%) which was the same across all ages and ethnicity. The main reason for not reporting was potential impact on their career, and the negative attitude it would engender. Of those who had reported it, two-thirds were not satisfied with the way it was dealt with, eg it was not taken seriously by chambers, it impacted on career progression or attitudes towards them. Of the one-third who were satisfied, a number highlighted that the source was from outside chambers, eg solicitors.

In general

About 70% of respondents felt that the culture and work environment in chambers was supportive and fair and that leadership of their organisation was supportive of gender equality. Mentoring or seminars were most often cited as the means of support for career progression. Nevertheless, 68.3% of all respondents had considered leaving the Bar. This was more prevalent amongst women who were BAME (73.4%), or were primary carers for children (72.6%) or who had experienced harassment (65%) or discrimination (69.8%) or both (79.5%). The demands of the profession, stress, and the unpredictability of work and timetabling also played their part. Clearly these issues cannot be divorced from the matters of retention and career progression.

The survey is worth reading in detail. What the Equality Rules seek to achieve are important in their own right. The failure to honour them in letter and spirit can impact on diversity and retention as much as problems over publicly funded fees. Unlike the latter, the attractiveness of the Bar as a profession is within our own power. Changing some of the culture of the Bar, ridding it of harassment and discrimination, and providing more support around childcare responsibilities and flexible working we can do ourselves.

Contributor David Wurtzel, Counsel Editorial Board and Bencher of Middle Temple

Combating unfair treatment at the Bar

One of the reasons for introducing the BSB‘s Equality Rules in 2012 was to address the lack of progression of women at the Bar and the high attrition rate, writes the Bar Standards Board. While our recent report showed evidence of good practice and progress in several areas, it also showed that problems remain with women experiencing unfair treatment. We need to work together to address these concerns. Our aim is to support practices in implementing policies that drive equality at the Bar. With this in mind, here is a helpful reminder of some of the important ways that unfair treatment can be combatted:

Although we are still a long way from a Bar which is gender equal, we want a Bar in which men and women, white and BAME (black and minority ethnic) barristers are treated equally. In some respects this does not happen. Women barristers still suffer harassment and/or discrimination at the hands of male barristers and clerks. Because of the perceived impact on their practices, overwhelmingly the women do not report it. We have known this as a statistical fact at least since the comprehensive reports Barristers Working Lives in 2011 and 2013. In 2014 the Bar Council commissioned the report Snapshot: The Experience of Self-Employed Women at the Bar. Seventy-three women, most of whom were over 15 years’ Call, recorded their experiences and concerns in focus groups. It was emphasised that most if not all of the examples cited of inappropriate behaviour ’were in the past’ and reports of recent sexual harassment were ’rare’.

A fuller and more accurate picture has emerged from the research published in July by the Bar Standards Board (Women at the Bar). The starting point was the 2012 Equality Rules which reflect the legislation which applies to the employed but not to the self-employed Bar. Have the Rules been adhered to, were barristers aware of whether their chambers had implemented them, were they satisfied with them, and had they made a difference? An online survey was sent to all women barristers: 1,333, 23% of the total, replied. Although self-selecting, the respondents in fact reflected the actual range of seniority and age of women barristers. Some employed barristers, in any event protected by statutory rights, also replied.

Recruitment

Chambers are obliged to ensure that recruitment and selection processes use objective and fair criteria. The BSB requires every member of a selection panel to be trained in fair recruitment and selection processes. Eighty per cent of self-employed respondents (but 65.6% of employed barristers) agreed that recruitment was fair, and most said that their panel members had undergone the training.

Work allocation

The Equality Rules require chambers to review the allocation of unassigned work regularly, collecting and analysing data broken down by race, disability and gender, and taking appropriate remedial action in respect of disparities in the data. The majority of respondents (52.2%) did not know whether their chambers did this or not, the highest figure being for those under five years’ Call, who might be thought to be most affected. 71.6% of respondents said that they had not queried how work had been allocated to them; again, it was those under five years’ Call who were in the higher numbers here. About half of those who did query what was going on felt that there was an improvement after that while the other half did not receive a suitable explanation or found that things changed for the worse. Some pointed out problems, such as, if clerks were trying to steer solicitors towards a particular barrister, the work did not count as ’unassigned’. Over a quarter had negative experiences, a lack of transparency being often cited, but a third had positive things to say about how the clerks made every effort to keep everyone employed to the extent that they wanted to be.

Working flexibly

Under the Equality Rules, chambers are required to have a flexible working policy which covers the rights of tenants to take a career break, to work part time, flexible hours or from home, and also a detailed maternity/paternity leave policy.

Of self-employed respondents, 58.4% said their chambers had a flexible working policy; 10.2% said that theirs did not. 58% thought their policy was excellent or good; only 6.6% thought it poor or very poor. Of those who had requested flexible working, 64.4% did so because of caring responsibilities for children. Of those who had applied, 85% had their request granted. Some of those, however, did not always get a rent rebate which would have made it financially practical. Of those who did not do flexible working, the most common concerns were the impact on income, the demands of courtroom practice and the issue of fixed chambers expenses.

Some 73% of self-employed respondents agreed that flexible working had helped them to remain at the Bar but only 25.6% agreed that it had supported their progression at the Bar. Over 60% cited negative impacts on their practice or progression, the most common impact being the quality or quantity of work they received; 10% highlighted negative attitudes towards flexible working from chambers, clients or clerks.

As for a maternity/paternity leave policy, a majority felt that their leave policy was good or excellent though this varied dramatically depending on whether chambers had consulted on it. How well had chambers supported those who took leave? 53.7% thought that support before leave was good or excellent but only 44% so rated support during leave and 47.8% so rated it after leave when 28.5% rated it poor or very poor.

Although a majority (53.6%) felt that being able to take this leave had helped them to stay at the Bar, 70% noted a sometimes significant negative impact on their practice or progression, with loss of clients and contacts and financial issues (such as fixed chambers rent) which caused some to return earlier than planned. Some reported that they were now considered to be less committed to the Bar and were assumed to be the secondary earner in the family.

Harassment

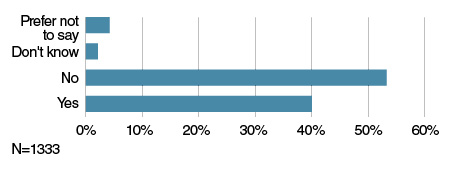

Remarkably only 48% of self-employed barrister respondents knew whether chambers had a harassment policy or not but the majority of those who did know thought it was good or excellent. Policy or not, 40% of the respondents said that they had experienced harassment at the Bar but this differed according to ethnicity: 48% of BAME respondents replied ’Yes’ compared to 38.4% of white women. Half of those who experienced it said that it came from members of chambers including their pupil supervisor or the clerks; the other half said it came from other barristers, judges or solicitors. Overall over half experienced it during pupillage. It appears to have been more prevalent in the past – 48.7% of women over 20 years Call or over had experienced it – but under 15 years’ Call the percentage of those who had experienced it was very much the same including 34.4% of those under five years’ Call. 43% of those who experienced it had done so after the 2012 Rules had been introduced. Sadly harassment is not ’rare’ and it is still happening.

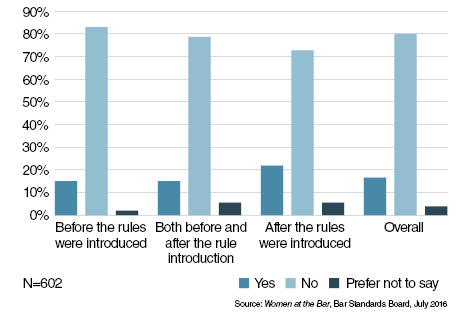

80.3% had not reported it. Of these 40% cited ’harming career prospects’ as the reason – gaining a tenancy, obtaining work, being known as a troublemaker– and a quarter cited cultural attitudes of the Bar towards harassment (‘an occupational hazard’) or the reporting of it. A quarter felt it had not been serious enough to report, and they were able to deal with it informally. Those who had reported it split equally between those who were satisfied with the response and those who were not.

Have you ever experienced harassment at the Bar?

Did you report the harassment you experienced?

Discrimination

In contrast to the questions about harassment, more women (45% of respondents) stated that they had experienced discrimination than those who stated that they had not (35.6%). Higher ‘Yes‘ responses came from those who were primary carers for their children (48.6%) and from BAME barristers, 54.2% of whom stated that they had experienced discrimination. A majority of those who experienced it had done so even after the Rules were introduced but overall the figures vary considerably depending on seniority: 56.4% of women over 20 years‘ Call had experienced it compared to 40.2% of those of five to nine years‘ Call and 32.8% for women under five years‘ Call. Some 60% said it came from within chambers or their organisation; over half stated that it related to the behaviour of their clerks and/or the allocation of work.

Once more there was a high figure for non-reporting (78.4%) which was the same across all ages and ethnicity. The main reason for not reporting was potential impact on their career, and the negative attitude it would engender. Of those who had reported it, two-thirds were not satisfied with the way it was dealt with, eg it was not taken seriously by chambers, it impacted on career progression or attitudes towards them. Of the one-third who were satisfied, a number highlighted that the source was from outside chambers, eg solicitors.

In general

About 70% of respondents felt that the culture and work environment in chambers was supportive and fair and that leadership of their organisation was supportive of gender equality. Mentoring or seminars were most often cited as the means of support for career progression. Nevertheless, 68.3% of all respondents had considered leaving the Bar. This was more prevalent amongst women who were BAME (73.4%), or were primary carers for children (72.6%) or who had experienced harassment (65%) or discrimination (69.8%) or both (79.5%). The demands of the profession, stress, and the unpredictability of work and timetabling also played their part. Clearly these issues cannot be divorced from the matters of retention and career progression.

The survey is worth reading in detail. What the Equality Rules seek to achieve are important in their own right. The failure to honour them in letter and spirit can impact on diversity and retention as much as problems over publicly funded fees. Unlike the latter, the attractiveness of the Bar as a profession is within our own power. Changing some of the culture of the Bar, ridding it of harassment and discrimination, and providing more support around childcare responsibilities and flexible working we can do ourselves.

Contributor David Wurtzel, Counsel Editorial Board and Bencher of Middle Temple

Combating unfair treatment at the Bar

One of the reasons for introducing the BSB‘s Equality Rules in 2012 was to address the lack of progression of women at the Bar and the high attrition rate, writes the Bar Standards Board. While our recent report showed evidence of good practice and progress in several areas, it also showed that problems remain with women experiencing unfair treatment. We need to work together to address these concerns. Our aim is to support practices in implementing policies that drive equality at the Bar. With this in mind, here is a helpful reminder of some of the important ways that unfair treatment can be combatted:

Almost half of women at the Bar have encountered discrimination and over two-thirds have considered leaving. David Wurtzel analyses the survey findings

We want the Bar to reflect the society it serves.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar