*/

‘I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.’ Audre Lorde

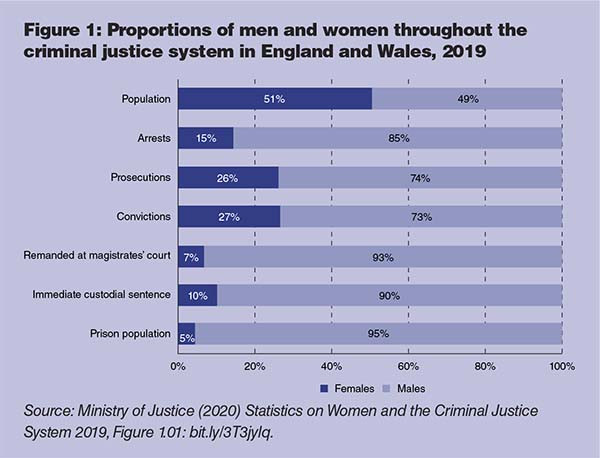

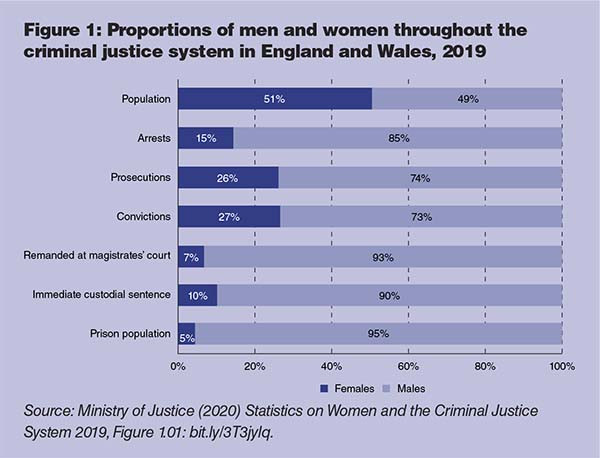

Time and time again when we discuss our research at work and social gatherings we are asked the same question – but why women? We explain that crime and punishment are gendered; that international criminal justice systems (CJSs) are dominated by men and underrepresented by women. Women represent roughly half of the general population in most countries, but remain a minority in CJSs across the globe. Taking England and Wales as an example, we can see the smaller proportion of women throughout all stages of criminal justice (see Figure 1 below).

And again, we might be asked – but why women? If they are so small in number then surely they are less of a priority? Can’t systems be adapted from ‘what works’ for men to account for women? In short – no. There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates that men and women’s experiences of criminal justice are not the same. Women’s experiences are distinct and, in many instances, represent a group who are vulnerable, marginalised and ignored. The Handbook we have recently edited draws attention to many of these issues and its nine themes are summarised below.

*

The vulnerabilities that women currently present with are often not new. We can see throughout history how women have been marginalised and treated differently to male counterparts. Theory, although often a little more difficult to engage with, when appropriately applied helps provide a lens to which we can understand women’s experiences of criminal justice. Commonalities across time and space show that there is something particular about being female within justice contexts.

Likewise, international research shows that women’s routes into the CJS, their histories and circumstances upon entering often follow a similar pattern. Women in the CJS often report repeated victimisation and abuse (as children and adults), have difficult relationships with substances, and/or come from marginalised socio-economic sections of communities. Education, access to paid employment, housing and familial circumstances are all factors that might increase their exposure to criminal justice. It is both their position in society, and interactions within it, that have significance for this trajectory into the CJS.

This is why intersectional narratives are key when considering women’s experiences of criminal justice. Aspects of women’s identity, including race and ethnicity, faith, culture and sexuality are all significant to their experiences. While it is important to look at women’s experiences, it is also important not to treat women as an homogenous group. By considering different aspects of their identity we can gain a better understanding of their specific challenges, needs and best practice.

The treatment of women by criminal justice agencies, and those working within these agencies, are also distinct to men. Interactions with professionals representing the police, courts, prisons and probation are heavily gendered. Societal expectations and norms are applied to women, even if unconsciously. We know that sentencing and the courts are heavily gendered, and women and girls who deviate from such norms are disadvantaged by pre-existing ideals.

Offence-specific experiences must also be considered. Not only is the legal framework different for specific offences and across jurisdictions, but societal reactions and emotions impact the way a woman might navigate and experience the system because of the nature of the offence.

We see significant commonalities in incarcerated women’s experiences across the globe. Despite making up a small minority of the prison population internationally, many of these women must negotiate harms of imprisonment heavily shaped by pre-existing factors within their lives and their interactions with others. Often these harms occur from prison systems being geared towards men and from gender-specific interventions being poorly dispersed or largely unavailable.

This lack of support is particularly acute when we consider the number of women who are also mothers, and how their contact with the CJS disrupts and impacts their families. The numerous gendered expectations placed on women relate to their perceived role as a ‘good’ mother or wife/partner, and their role as caregivers adds additional layers of strain when they become involved in the CJS.

Many women in the CJS receive community sentences, and those exiting prison have contact with probation services. Rehabilitation and reintegration is therefore incredibly gendered, and in many cases the challenges faced by women as a consequence of their criminal justice exposure have long lasting implications in the community for themselves, their children and families. Structural issues, eg unsuitable accommodation, inhibit desistance and resettlement attempts.

There is much scope to support women in a way that accounts for their gender-specific needs. Frontline practitioners in the CJS are uniquely placed to identify women’s vulnerabilities and appropriately respond to them, making it critical to explore the nature and quality of these practitioner relationships, and to identify best practice when and where it occurs.

The issues discussed here are not just relevant to those who identify as women, those with lived experience, and those who have family, friends and significant others with lived experience. It is vitally important that the whole of society, not just those working in the law, are aware of these different experiences. Barristers have the unique power to end or at least stem these harms. By engaging with this, or taking time to further consider women in your professional role, you can help to make meaningful change.

It is the enduring harms associated with the multifaceted issues described in this article that the Routledge Handbook of Women’s Experiences of Criminal Justice, Masson, I and Booth, N (Eds) (2022) brings together the voices of a range of contributors who are seeking to challenge the status quo.

‘I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.’ Audre Lorde

Time and time again when we discuss our research at work and social gatherings we are asked the same question – but why women? We explain that crime and punishment are gendered; that international criminal justice systems (CJSs) are dominated by men and underrepresented by women. Women represent roughly half of the general population in most countries, but remain a minority in CJSs across the globe. Taking England and Wales as an example, we can see the smaller proportion of women throughout all stages of criminal justice (see Figure 1 below).

And again, we might be asked – but why women? If they are so small in number then surely they are less of a priority? Can’t systems be adapted from ‘what works’ for men to account for women? In short – no. There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates that men and women’s experiences of criminal justice are not the same. Women’s experiences are distinct and, in many instances, represent a group who are vulnerable, marginalised and ignored. The Handbook we have recently edited draws attention to many of these issues and its nine themes are summarised below.

*

The vulnerabilities that women currently present with are often not new. We can see throughout history how women have been marginalised and treated differently to male counterparts. Theory, although often a little more difficult to engage with, when appropriately applied helps provide a lens to which we can understand women’s experiences of criminal justice. Commonalities across time and space show that there is something particular about being female within justice contexts.

Likewise, international research shows that women’s routes into the CJS, their histories and circumstances upon entering often follow a similar pattern. Women in the CJS often report repeated victimisation and abuse (as children and adults), have difficult relationships with substances, and/or come from marginalised socio-economic sections of communities. Education, access to paid employment, housing and familial circumstances are all factors that might increase their exposure to criminal justice. It is both their position in society, and interactions within it, that have significance for this trajectory into the CJS.

This is why intersectional narratives are key when considering women’s experiences of criminal justice. Aspects of women’s identity, including race and ethnicity, faith, culture and sexuality are all significant to their experiences. While it is important to look at women’s experiences, it is also important not to treat women as an homogenous group. By considering different aspects of their identity we can gain a better understanding of their specific challenges, needs and best practice.

The treatment of women by criminal justice agencies, and those working within these agencies, are also distinct to men. Interactions with professionals representing the police, courts, prisons and probation are heavily gendered. Societal expectations and norms are applied to women, even if unconsciously. We know that sentencing and the courts are heavily gendered, and women and girls who deviate from such norms are disadvantaged by pre-existing ideals.

Offence-specific experiences must also be considered. Not only is the legal framework different for specific offences and across jurisdictions, but societal reactions and emotions impact the way a woman might navigate and experience the system because of the nature of the offence.

We see significant commonalities in incarcerated women’s experiences across the globe. Despite making up a small minority of the prison population internationally, many of these women must negotiate harms of imprisonment heavily shaped by pre-existing factors within their lives and their interactions with others. Often these harms occur from prison systems being geared towards men and from gender-specific interventions being poorly dispersed or largely unavailable.

This lack of support is particularly acute when we consider the number of women who are also mothers, and how their contact with the CJS disrupts and impacts their families. The numerous gendered expectations placed on women relate to their perceived role as a ‘good’ mother or wife/partner, and their role as caregivers adds additional layers of strain when they become involved in the CJS.

Many women in the CJS receive community sentences, and those exiting prison have contact with probation services. Rehabilitation and reintegration is therefore incredibly gendered, and in many cases the challenges faced by women as a consequence of their criminal justice exposure have long lasting implications in the community for themselves, their children and families. Structural issues, eg unsuitable accommodation, inhibit desistance and resettlement attempts.

There is much scope to support women in a way that accounts for their gender-specific needs. Frontline practitioners in the CJS are uniquely placed to identify women’s vulnerabilities and appropriately respond to them, making it critical to explore the nature and quality of these practitioner relationships, and to identify best practice when and where it occurs.

The issues discussed here are not just relevant to those who identify as women, those with lived experience, and those who have family, friends and significant others with lived experience. It is vitally important that the whole of society, not just those working in the law, are aware of these different experiences. Barristers have the unique power to end or at least stem these harms. By engaging with this, or taking time to further consider women in your professional role, you can help to make meaningful change.

It is the enduring harms associated with the multifaceted issues described in this article that the Routledge Handbook of Women’s Experiences of Criminal Justice, Masson, I and Booth, N (Eds) (2022) brings together the voices of a range of contributors who are seeking to challenge the status quo.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar