*/

If the Bar is complacent on the issue of race, then we will perpetuate the same racial inequities that continue to pervade our society, writes Professor Leslie Thomas QC

‘We look forward to the day when actions speak louder than words.’

Sue Woodfsord-Hollick OBE, Stuart Hall Foundation patron

‘For more than fifty years, successive British governments have tried to tackle the enduring nature of racism and the consequences of structural racial inequality through legislative interventions. However, in 2020, racism and racial inequality persist.’

Dr Stephen D Ashe, Stuart Hall Foundation Race Report, February 2021

On 20 April 2021 at approximately 10pm UK time, a US jury returned verdicts in the Derek Chauvin murder trial. Guilty on all counts for the homicide of George Floyd. This was a rare acknowledgement of accountability for the unlawful death of a Black man.

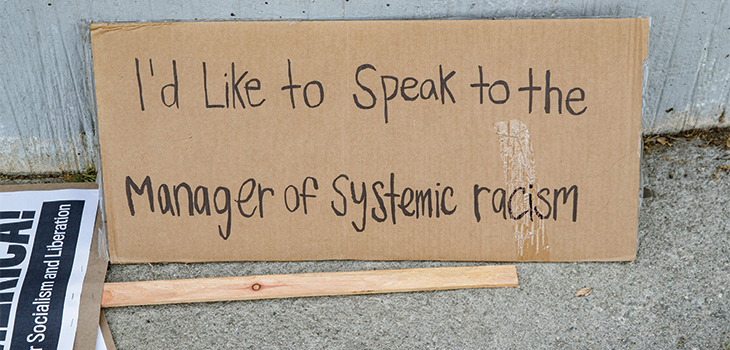

As I write, it has been just under a year since Floyd’s death, and a year since my first article on this subject for Counsel magazine. A lot has happened in the past year. The world has changed significantly. Many of us know someone who has passed due to COVID-19. We have undergone three lockdowns, a travel ban, pressure at home living during a pandemic and – for the first time for some – have had to confront and take a good look at ourselves and our practices in the wake of Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter protests which were sparked following that murder. I feel that, particularly at the Bar and in legal circles more widely, there is a genuine desire to effect the much needed change we all crave.

But at times I feel that for every step forward we take, there is a setback – and then we find ourselves back where we started, or even further back.

For all the progress that was made last year, with fresh and honest discussions in all areas of social life about how we could all do better and acknowledging and recognising the structural inequalities that put many Black people at an unfair disadvantage, the pushback on this narrative was inevitable. Surprisingly it came from the government’s own appointed ‘race experts’, the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities (CRED) Report published on 31 March 2021.

That report and its findings have been widely condemned. One example is in a letter dated 18 April 2021 to the Prime Minister from the TUC:

‘BME workers are overrepresented in lower paid, insecure jobs and have to send 60 per cent more job applications to be invited to interview. Currently, the BME unemployment rate is running at almost double that of white workers. And BME workers in London, the region with the highest BME population, experience a 24 per cent pay gap.

These inequalities are compounded by the direct discrimination BME people face within workplaces: around a quarter (24 per cent) had been singled out for redundancy and one in seven (15 per cent) of those that had experienced racist harassment at work said they left their job as a result.’

In a statement dated 19 April 2021, the UN Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent categorically rejected and condemned the CRED’s analysis and findings:

‘Stunningly, the Report also claims that, while there might be overt acts of racism in the UK, there is no institutional racism. The Report offers no evidence for this claim, but openly blames identity politics, disparages complex analyses of race and ethnicity using qualitative and quantitative research, proffers shocking misstatements and/or misunderstandings about data collection and mixed methods research, cites “pessimism”, “linguistic inflation”, and “emotion” as bases to distrust data and narratives associated with racism and racial discrimination, and attempts to delegitimize data grounded in lived experience while also shifting the blame for the impacts of racism to the people most impacted by it.’

The UN experts, in their damning conclusion, state:

‘In 2021, it is stunning to read a report on race and ethnicity that repackages racist tropes and stereotypes into fact, twisting data and misapplying statistics and studies into conclusory findings and ad hominem attacks on people of African descent. The Report attacks the credibility of those working to mitigate and lessen institutional racism while denying the role of institutions, including educators and educational institutions, in the data on the expectations and aspirations of boys and girls of African descent. The Report cites dubious evidence to make claims that rationalize white supremacy by using the familiar arguments that have always justified racial hierarchy.’

So where does that leave us? Can we all take a collective sigh of relief and rely on the CRED Report? Some of us in this profession may be confused as to whether institutional racism still exists in British society. I think it is important to be clear about what we are speaking about. The concept of institutional racism was coined in 1967 by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V Hamilton (Black Power: The Politics of Liberation):

‘Racism is both overt and covert. It takes two, closely related forms: individual whites acting against individual blacks, and acts by the total white community against the black community. We call these individual racism and institutional racism. The first consists of overt acts by individuals, which cause death, injury or the violent destruction of property. This type can be recorded by television cameras; it can frequently be observed in the process of commission. The second type is less overt, far more subtle, less identifiable in terms of specific individuals committing the acts. But it is no less destructive of human life. The second type originates in the operation of established and respected forces in the society, and thus receives far less public condemnation than the first type. When white terrorists bomb a black church and kill five black children, that is an act of individual racism, widely deplored by most segments of the society. But when in that same city – Birmingham, Alabama – five hundred black babies die each year because of the lack of proper food, shelter and medical facilities, and thousands more are destroyed and maimed physically, emotionally and intellectually because of conditions of poverty and discrimination in the black community, that is a function of institutional racism. When a black family moves into a home in a white neighborhood and is stoned, burned or routed out, they are victims of an overt act of individual racism which many people will condemn – at least in words. But it is institutional racism that keeps black people locked in dilapidated slum tenements, subject to the daily prey of exploitative slumlords, merchants, loan sharks and discriminatory real estate agents. The society either pretends it does not know of this latter situation, or is in fact incapable of doing anything meaningful about it.’

In 1999, the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Report by Sir William Macpherson, said:

‘6.17 Unwitting racism can arise because of lack of understanding, ignorance or mistaken beliefs. It can arise from well intentioned but patronising words or actions. It can arise from unfamiliarity with the behaviour or cultural traditions of people or families from minority ethnic communities. It can arise from racist stereotyping of black people as potential criminals or troublemakers. Often this arises out of uncritical self-understanding born out of an inflexible police ethos of the ‘traditional’ way of doing things. Furthermore such attitudes can thrive in a tightly knit community, so that there can be a collective failure to detect and to outlaw this breed of racism. The police canteen can too easily be its breeding ground.’

Let me ask the question: why are the robing rooms or the closeted plush chambers of those of us at the Bar any more immune from discrimination? Is it because we consider ourselves higher mortals? Reasonable and intellectual people who cannot be affected by racism?

As the Macpherson Report found:

‘6.34 Taking all that we have heard and read into account we grapple with the problem. For the purposes of our Inquiry the concept of institutional racism which we apply consists of:

The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin. It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people.

It persists because of the failure of the organisation openly and adequately to recognise and address its existence and causes by policy, example and leadership. Without recognition and action to eliminate such racism it can prevail as part of the ethos or culture of the organisation. It is a corrosive disease.’ (emphasis added)

The Report went on to say:

‘6.39 Given the central nature of the issue we feel that it is important at once to state our conclusion that institutional racism, within the terms of its description set out in Paragraph 6.34 above, exists both in the Metropolitan Police Service and in other Police Services and other institutions countrywide.’ (emphasis added)

‘Other institutions’ include the legal profession and the Bar. Some harsh realities need to be confronted. The ‘other institutions’ include our profession. Yes, the Bar. Once said to be a ‘gentleman’s’ profession, even with all the misogyny of that grand title. The fact is that the Bar has discriminated against individuals on all levels including gender, class, disability and – yes – race. The statistics are alarming and saddening and there is no room for complacency.

Diversity at the Bar 2020 statistics and the Bar Standards Board’s November 2020 report Income at the Bar – by Gender and Ethnicity make uncomfortable reading. It has long been well known that there is an underrepresentation of people of colour in the Chancery and commercial Bar and in other specialist sectors. Why are there more people of colour in less lucrative and/or publicly funded areas such as crime? And even where we have Black talent, what is the excuse for Black people on average, and particularly Black women, earning lower fees than their counterparts of other races? Why is there is still a gross underrepresentation of Black people in the judiciary?

We have to acknowledge and accept the truth, no matter how uncomfortable. I found a quote from an old online thread on a student forum when researching this article. The quote perhaps epitomises how many white people (who may be well intentioned) genuinely feel:

‘I am a white male who has enjoyed relatively good success in my life. I feel I have earned it and I resent when it is implied that my success is attributed to privilege. Many of those who lack a measure of success resent it when it is implied that their shortcoming is attributed to anything other than a lack of privilege.’ (thestudentroom.co.uk)

But as Peggy McIntosh, in White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (1989), points out:

‘I think whites are carefully taught not to recognize white privilege, as males are taught not to recognize male privilege. So I have begun in an untutored way to ask what it is like to have white privilege. I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was “meant” to remain oblivious. White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools, and blank checks.’

The fact is that we live in a society steeped in centuries of racism. Black people in all walks of life face barriers that white people do not – ranging from the vast racial disparities in the criminal justice system, to the racial wealth and income gap, to the continuing racial inequities in business and the professions. The Bar is no different. To say that white lawyers have white privilege is not to suggest that they did not work hard or do not deserve their success. It is simply to say that they do not face the additional barriers that their Black colleagues do. If we, as a profession, are complacent on the issue of race, if we do nothing, then we will perpetuate the same racial inequities that pervade our society. It is not enough to be ‘non-racist’ – we need to be actively anti-racist.

‘We look forward to the day when actions speak louder than words.’

Sue Woodfsord-Hollick OBE, Stuart Hall Foundation patron

‘For more than fifty years, successive British governments have tried to tackle the enduring nature of racism and the consequences of structural racial inequality through legislative interventions. However, in 2020, racism and racial inequality persist.’

Dr Stephen D Ashe, Stuart Hall Foundation Race Report, February 2021

On 20 April 2021 at approximately 10pm UK time, a US jury returned verdicts in the Derek Chauvin murder trial. Guilty on all counts for the homicide of George Floyd. This was a rare acknowledgement of accountability for the unlawful death of a Black man.

As I write, it has been just under a year since Floyd’s death, and a year since my first article on this subject for Counsel magazine. A lot has happened in the past year. The world has changed significantly. Many of us know someone who has passed due to COVID-19. We have undergone three lockdowns, a travel ban, pressure at home living during a pandemic and – for the first time for some – have had to confront and take a good look at ourselves and our practices in the wake of Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter protests which were sparked following that murder. I feel that, particularly at the Bar and in legal circles more widely, there is a genuine desire to effect the much needed change we all crave.

But at times I feel that for every step forward we take, there is a setback – and then we find ourselves back where we started, or even further back.

For all the progress that was made last year, with fresh and honest discussions in all areas of social life about how we could all do better and acknowledging and recognising the structural inequalities that put many Black people at an unfair disadvantage, the pushback on this narrative was inevitable. Surprisingly it came from the government’s own appointed ‘race experts’, the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities (CRED) Report published on 31 March 2021.

That report and its findings have been widely condemned. One example is in a letter dated 18 April 2021 to the Prime Minister from the TUC:

‘BME workers are overrepresented in lower paid, insecure jobs and have to send 60 per cent more job applications to be invited to interview. Currently, the BME unemployment rate is running at almost double that of white workers. And BME workers in London, the region with the highest BME population, experience a 24 per cent pay gap.

These inequalities are compounded by the direct discrimination BME people face within workplaces: around a quarter (24 per cent) had been singled out for redundancy and one in seven (15 per cent) of those that had experienced racist harassment at work said they left their job as a result.’

In a statement dated 19 April 2021, the UN Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent categorically rejected and condemned the CRED’s analysis and findings:

‘Stunningly, the Report also claims that, while there might be overt acts of racism in the UK, there is no institutional racism. The Report offers no evidence for this claim, but openly blames identity politics, disparages complex analyses of race and ethnicity using qualitative and quantitative research, proffers shocking misstatements and/or misunderstandings about data collection and mixed methods research, cites “pessimism”, “linguistic inflation”, and “emotion” as bases to distrust data and narratives associated with racism and racial discrimination, and attempts to delegitimize data grounded in lived experience while also shifting the blame for the impacts of racism to the people most impacted by it.’

The UN experts, in their damning conclusion, state:

‘In 2021, it is stunning to read a report on race and ethnicity that repackages racist tropes and stereotypes into fact, twisting data and misapplying statistics and studies into conclusory findings and ad hominem attacks on people of African descent. The Report attacks the credibility of those working to mitigate and lessen institutional racism while denying the role of institutions, including educators and educational institutions, in the data on the expectations and aspirations of boys and girls of African descent. The Report cites dubious evidence to make claims that rationalize white supremacy by using the familiar arguments that have always justified racial hierarchy.’

So where does that leave us? Can we all take a collective sigh of relief and rely on the CRED Report? Some of us in this profession may be confused as to whether institutional racism still exists in British society. I think it is important to be clear about what we are speaking about. The concept of institutional racism was coined in 1967 by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V Hamilton (Black Power: The Politics of Liberation):

‘Racism is both overt and covert. It takes two, closely related forms: individual whites acting against individual blacks, and acts by the total white community against the black community. We call these individual racism and institutional racism. The first consists of overt acts by individuals, which cause death, injury or the violent destruction of property. This type can be recorded by television cameras; it can frequently be observed in the process of commission. The second type is less overt, far more subtle, less identifiable in terms of specific individuals committing the acts. But it is no less destructive of human life. The second type originates in the operation of established and respected forces in the society, and thus receives far less public condemnation than the first type. When white terrorists bomb a black church and kill five black children, that is an act of individual racism, widely deplored by most segments of the society. But when in that same city – Birmingham, Alabama – five hundred black babies die each year because of the lack of proper food, shelter and medical facilities, and thousands more are destroyed and maimed physically, emotionally and intellectually because of conditions of poverty and discrimination in the black community, that is a function of institutional racism. When a black family moves into a home in a white neighborhood and is stoned, burned or routed out, they are victims of an overt act of individual racism which many people will condemn – at least in words. But it is institutional racism that keeps black people locked in dilapidated slum tenements, subject to the daily prey of exploitative slumlords, merchants, loan sharks and discriminatory real estate agents. The society either pretends it does not know of this latter situation, or is in fact incapable of doing anything meaningful about it.’

In 1999, the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Report by Sir William Macpherson, said:

‘6.17 Unwitting racism can arise because of lack of understanding, ignorance or mistaken beliefs. It can arise from well intentioned but patronising words or actions. It can arise from unfamiliarity with the behaviour or cultural traditions of people or families from minority ethnic communities. It can arise from racist stereotyping of black people as potential criminals or troublemakers. Often this arises out of uncritical self-understanding born out of an inflexible police ethos of the ‘traditional’ way of doing things. Furthermore such attitudes can thrive in a tightly knit community, so that there can be a collective failure to detect and to outlaw this breed of racism. The police canteen can too easily be its breeding ground.’

Let me ask the question: why are the robing rooms or the closeted plush chambers of those of us at the Bar any more immune from discrimination? Is it because we consider ourselves higher mortals? Reasonable and intellectual people who cannot be affected by racism?

As the Macpherson Report found:

‘6.34 Taking all that we have heard and read into account we grapple with the problem. For the purposes of our Inquiry the concept of institutional racism which we apply consists of:

The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin. It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people.

It persists because of the failure of the organisation openly and adequately to recognise and address its existence and causes by policy, example and leadership. Without recognition and action to eliminate such racism it can prevail as part of the ethos or culture of the organisation. It is a corrosive disease.’ (emphasis added)

The Report went on to say:

‘6.39 Given the central nature of the issue we feel that it is important at once to state our conclusion that institutional racism, within the terms of its description set out in Paragraph 6.34 above, exists both in the Metropolitan Police Service and in other Police Services and other institutions countrywide.’ (emphasis added)

‘Other institutions’ include the legal profession and the Bar. Some harsh realities need to be confronted. The ‘other institutions’ include our profession. Yes, the Bar. Once said to be a ‘gentleman’s’ profession, even with all the misogyny of that grand title. The fact is that the Bar has discriminated against individuals on all levels including gender, class, disability and – yes – race. The statistics are alarming and saddening and there is no room for complacency.

Diversity at the Bar 2020 statistics and the Bar Standards Board’s November 2020 report Income at the Bar – by Gender and Ethnicity make uncomfortable reading. It has long been well known that there is an underrepresentation of people of colour in the Chancery and commercial Bar and in other specialist sectors. Why are there more people of colour in less lucrative and/or publicly funded areas such as crime? And even where we have Black talent, what is the excuse for Black people on average, and particularly Black women, earning lower fees than their counterparts of other races? Why is there is still a gross underrepresentation of Black people in the judiciary?

We have to acknowledge and accept the truth, no matter how uncomfortable. I found a quote from an old online thread on a student forum when researching this article. The quote perhaps epitomises how many white people (who may be well intentioned) genuinely feel:

‘I am a white male who has enjoyed relatively good success in my life. I feel I have earned it and I resent when it is implied that my success is attributed to privilege. Many of those who lack a measure of success resent it when it is implied that their shortcoming is attributed to anything other than a lack of privilege.’ (thestudentroom.co.uk)

But as Peggy McIntosh, in White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (1989), points out:

‘I think whites are carefully taught not to recognize white privilege, as males are taught not to recognize male privilege. So I have begun in an untutored way to ask what it is like to have white privilege. I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was “meant” to remain oblivious. White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools, and blank checks.’

The fact is that we live in a society steeped in centuries of racism. Black people in all walks of life face barriers that white people do not – ranging from the vast racial disparities in the criminal justice system, to the racial wealth and income gap, to the continuing racial inequities in business and the professions. The Bar is no different. To say that white lawyers have white privilege is not to suggest that they did not work hard or do not deserve their success. It is simply to say that they do not face the additional barriers that their Black colleagues do. If we, as a profession, are complacent on the issue of race, if we do nothing, then we will perpetuate the same racial inequities that pervade our society. It is not enough to be ‘non-racist’ – we need to be actively anti-racist.

If the Bar is complacent on the issue of race, then we will perpetuate the same racial inequities that continue to pervade our society, writes Professor Leslie Thomas QC

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar