*/

Let’s talk about race. Forget the guilt and take action. Bias is implicit and often unconscious. It takes great courage to change the system. It benefits us all. By Leslie Thomas QC, Gresham Professor of Law

‘I regard it as a duty which I owed, not just to my people, but also to my profession, to the practice of law, and to the justice for all mankind, to cry out against this discrimination which is essentially unjust and opposed to the whole basis of the attitude towards justice which is part of the tradition of legal training in this country. I believed that in taking up a stand against this injustice I was upholding the dignity of what should be an honourable profession.’

Nelson Mandela

The first thing I want to make clear is that I am not a race expert and do not profess to be one. I have some ideas just like the rest of you, and like some of you, I have given the subject of how to improve diversity and particularly racial diversity some deeper thought and consideration.

Until February 2020, I was joint head of Garden Court Chambers, the second largest set of chambers in the country and also a very diverse working environment. I am very proud to be a member of Garden Court and of its diversity; but even we do not rest on our laurels, and we recognise there is much improvement to be done in all areas of diversity within our chambers.

I often wonder whether the Bar is moving forward, standing still or moving backward. The recent Bar Standards Board (BSB) statistics on diversity are not encouraging. At times I really think we are moving backward. (I am a barrister member of the BSB, although this article is written in a personal capacity.)

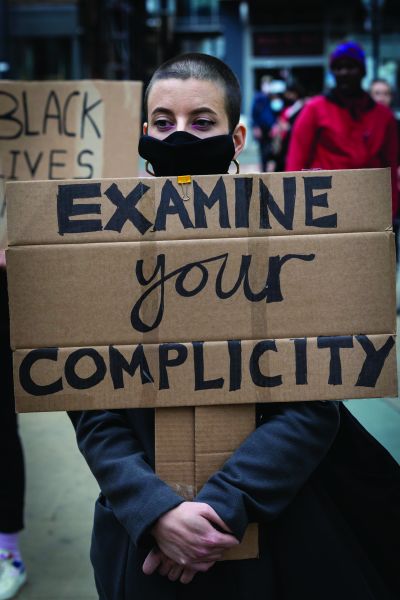

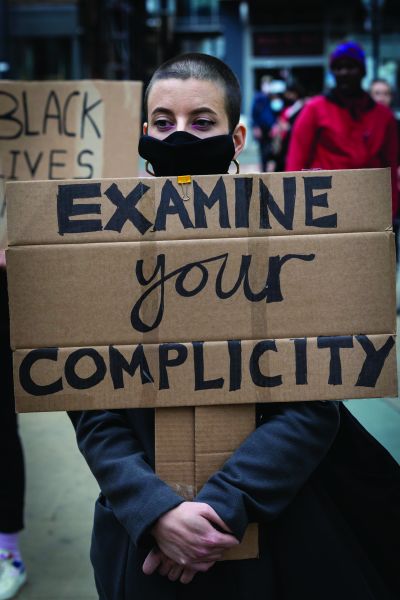

In the last week, two important things for me have happened. Firstly, there has been a real discussion about race in the public discourse following the horrific killing of an unarmed black man, whose death was captured on video and we see him dying before our eyes and calling out for his dead mother. This has led us all to ask questions about race, discrimination, racism and how to be anti-racist and live and work in truly anti-racist ways. Secondly, I was appointed as the first black professor of law for the prestigious Gresham College, a free public university with a 400-year history of providing free education. The timing seems uncanny. It is important for me, given the work to which I have dedicated my life, to discuss recent events and what we can do to bring change to our society.

Racism and discriminatory behaviours pervade all levels of society and our legal system is not immune from the same. I have experienced it many times in my career. One judge said to me, ‘Mr Thomas, in this country we do things in this way…’ Anyone who knows me, knows that I speak with a South London accent, of which I’m proud. Which country did he think I came from? I know the judge would not say that to one of my colleagues. I was deliberately ‘othered’; made to feel different. My story is not unique. Many of my colleagues from the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) community have similar stories. Just think about it: if I can be treated in this way and I am a member of a well-respected profession, it takes very little imagination to think how black defendants are treated.

Differential treatment of black and brown people occurs at all levels in the legal system; differential and unfavourable treatment in encounters with police, decisions as to whether to charge or not, bail or not, in the way they are prosecuted, sentenced, type of sentence, length of sentence, treatment in prison, how they are disciplined in prison, parole decisions and so on.

The Lammy Review in 2017, which analysed the disproportionate treatment of BAME people in the criminal justice system, makes for depressing reading. Some of the statistics will come as no surprise to anyone who has been following the news, such as the fact that black people are six times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than white people. But it is not just the police that have a race problem. It is the judiciary. The Lammy Review showed that BAME defendants were 240% more likely to be given a prison sentence for a drug offence than white defendants. Black people make up 3% of the general population, but make up 12% of prisoners and 21% of children in custody. Every single one of those black prisoners, including those black children, was sent to prison by a judge. Interestingly, the Review also found, by contrast, that there is no evidence of racial bias in juries’ decisions to convict or acquit – suggesting that our judges have a bigger race problem than our juries do.

Nor is it just criminal courts that have a race problem. In the immigration system – a system which traces its modern roots to the profoundly racist Commonwealth Immigrants Acts 1962 and 1968 and Immigration Act 1971 – judges sit in judgment on BAME people every day. Some of these people are seeking asylum in the UK and have experienced horrific traumas in their home countries. Some are victims of human trafficking and similar abuses. Some are people who have lived here most of their lives, are British in all but name, and are now being ripped apart from their home, their family and their children because of a criminal conviction. Sadly, if not surprisingly, the attitudes of the people who administer this system today can at times be as racist and colonialist as those of the people who created it in the 1960s and 1970s. One barrister told me that a white immigration judge, having heard an appeal by a Somali appellant, commented on how refreshing it was to see a Somali family working. The same barrister, who is herself black, was told by a different judge that it was nice to see her ‘sitting on this side of the table’, pointing to the side of the table where counsel sit. Another judge told her at a training event that she did not have ‘negroid features’.

Granted these are anecdotal accounts, but until a profession-wide survey of the experiences of BAME legal professionals – akin to the ground-breaking Women at the Bar 2016 study by the BSB of their experience of the equality rules in practice – it is what we have. Take the trouble to ask a BAME colleague about their experiences in the law and you will build your own picture.

The BSB has a statutory regulatory objective to ‘encourage an independent, strong, diverse and effective legal profession’ under the Legal Services Act 2007 (LSA 2007). The BSB is bound by several regulatory objectives as set out in s 1 of the LSA 2007. Section 1(1)(c) of the Act specifies the regulatory objective of ‘improving access to justice’. While the ability of the general public to access justice via the legal profession is not wholly under the control of the legal regulators, the BSB seeks to make improvements where it has an influence. Section 1(1)(f) of the LSA 2007 sets out the regulatory objective of ‘encouraging an independent, strong, diverse and effective legal profession’. The BSB also has obligations under the Equality Act 2010.

The general duty requires public bodies, in the exercise of their functions, to pay due regard to the need to ‘eliminate unlawful discrimination, harassment, and victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by, or under, the Equality Act’ (Equality Act aim 1); to advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it (Equality Act aim 2); and foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it (Equality Act aim 3). The BSB has this legal duty. It is part of its regulatory role.

I recently said at a BSB meeting that there is a real problem in getting this message across to the profession. There is no doubt that many sectors, practice areas and chambers within our profession lack racial diversity. In these modern times, our websites shine a light on how diverse we are. Anyone – whether lay client, professional client or member of the public – can access the profiles and photographs of our members and the truth is laid bare.

The Diversity at the Bar 2019 statistics published in January 2020 make uncomfortable reading.* It has long been well known there is an under-representation of people of colour in the Chancery and commercial bar and in other specialist sectors. Why are there more people of colour in less lucrative and/or publicly funded areas such as crime?

Why is there still a gross under-representation of black judges? In 2020 there are still no black male High Court judges. We had one full-time black woman High Court judge in recent times who has since retired (Dame Linda Dobbs QC DBE was a High Court judge from 2004 to 2013**). There are no black Court of Appeal or Supreme Court judges.

As I said at the BSB meeting, the problem is one of messaging. If top commercial chambers are predominantly ‘white, male and older’, getting a message across to them of change is implicitly saying there is something fundamentally wrong with you. This is a difficult message to swallow. It is always difficult to change and challenge the status quo, particularly from the outside. There has to be a willingness to tackle this from within.

But some harsh realities need to be confronted. Firstly, to discuss diversity and improving diversity particularly as it concerns race, there needs to be a proper and honest discussion about racism. You see, it is possible to get to the top of our profession without ever discussing racism. It is not a job requirement to get to the top of our profession. It is possible to turn a blind eye to it. We can pretend if we don’t see it, it isn’t there. We can be comfortable with the status quo or the cards we have been dealt with. However, the reality is there for all to see – if we care to look. We as a profession have to move beyond seeing racism as individual characteristics. We need to understand racism as a system, not an event. None of us are exempt from its forces. Racism impacts differently on different groups. I often ask myself why a discussion on race is such a difficult subject.

It is a flawed and outdated view on racism to believe that the racist is an individual who consciously does not like people based on race and is intentionally mean to them. Such a definition is a deflection which protects the system. When our profession recognises that racism doesn’t necessarily come from individuals, doesn’t need to be conscious, and doesn’t need to be intentional, we will be moving in the right direction. Racial injustice and racism isn’t a simple binary question. The racist needn’t simply be bad, ignorant, bigoted, prejudiced or old. The non-racist isn’t necessarily the good person, educated, progressive, open or fair-minded, well-intended or young. This discussion goes well beyond this.

If you believe your chambers are ‘colour-blind’ and treat everyone the same, then you have a problem. That mindset is the problem. ‘Colour blindness’ does not work in a system where everyone at the top of judicial power is white, everyone in the ‘best’ chambers is white, and the two ‘best’ universities in the country have a lack of black entrants. If you are a person of colour, just seeing this would set alarm bells going. We cannot just take race off the table. It needs to be discussed.

Barristers are all unique and different. It is also a fact that the reasons for any of us doing this job are too numerous to be able to make assumptions or value judgments about. But regardless of what that driver is for you as to why you chose law, we all have a common purpose. A golden thread that unites us all. We all provide public service.

A question I am often asked is ‘Have you suffered discrimination, or felt the effect of racism in this profession?’’

How many white people here have been asked that particular question, based on their race? Do you believe that discrimination exists in society? If the answer is yes? So why would we assume that it does not exist within our profession? So the big question is how do we change and improve our profession?

I believe we have to change mindsets. We do that, I believe, by getting our profession to buy into why they should feel the need to change. Asking why is such a powerful question. If you understand the ‘why’ that is the key, for potentially long-lasting and effective change. So why should we want to change? Why should we make our profession more diverse? What’s in it for the profession? Because each individual will be saying silently to themselves. What is in it for me? Or what is in it for us?

Now let’s think about this. If you are one of the over-represented groups in the profession you are in a position of privilege and power, like it or not, and there is an obvious natural tendency to think of increased diversity as a decrease in ‘us’. Turkeys if they had a vote wouldn’t vote for Christmas.

But we want to get the profession to understand that potential clients or colleagues may come from different backgrounds; that the Bar needs to perform its duties in a way that acknowledges differences and the impact of discrimination on people we engage with. This comes back to the question posed above; do you think that there is discrimination in society? Should we be working towards eliminating systemic cultural and direct discrimination from the profession?

We should seek to ensure that we all contribute to a stronger, more culturally diverse Bar; that the profession does not discriminate in how it provides its service; and we should try to foster and encourage the profession to welcome the introduction of new diverse talent and give fair and equal opportunity based on merit to the lawyers already within this profession.

It will need to be a very powerful one because it is a normal thing to want to keep things as they are. But regardless of where you come from, or on which side of the divide you fall, or what your current demographic representation is in our profession, diversity benefits us all.

One of the best articles and arguments I’ve seen for diversity comes from one of a series of articles from a New Zealand lawyer and mediator Paul Sills. He goes further than the reasons we currently give. He argues the following:

Sills concludes that:

‘People who have grown up in multicultural societies often find it not only normal but desirable to live with people of different backgrounds. Diversity is not merely tolerated, but something to be actively sought out.’

Sills’ arguments are powerful and persuasive. We all have to embrace these arguments. It’s the job of our profession to acknowledge and present these arguments persuasively and convincingly.

This leads to less push back or reluctance. It overcomes the suggestion that this is just politically correct talk. But it is so much more than this.

White members of our profession need to understand that questioning the way things currently are is not about them being attacked, shamed, accused or judged. These are normal reactions and to be expected. But it is more a recognition that we as a profession can improve our lot; questions of being good or bad are irrelevant. It is a recognition that advantage may well be tied to race and that is systemic. We should forget the guilt and take action. History matters. Bias is implicit and often unconscious. More importantly, it takes great courage to change this system.

We are barristers. In our profession, we are problem solvers, solution finders, and deep thinkers. We are a profession with the greatest minds.

So let’s talk about race.

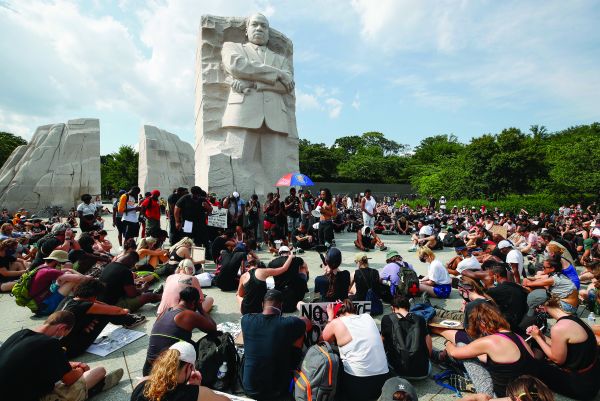

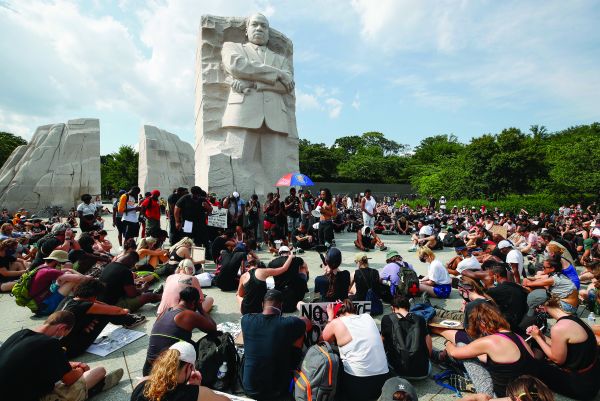

Postscript – I first penned this article before the brutal, horrific and heartless murder of George Floyd. This makes what I have to say even more relevant today. It was interesting to watch the hand wringing of people in our profession, as to whether they ought to put out statements condemning what they had seen, and whether they should support the statement ‘Black Lives Matter’. Some of the people wrestling with this ‘dilemma’ are well intentioned people. Some are professional colleagues I would describe as friends. However, in the words of the late MLK:

‘In the end we will remember not the words of our enemies but the silence of our friends.’

Martin Luther King Jr

* Diversity at the Bar 2019: The BSB report, published in January 2020, found that there is still a disparity between the overall percentage of BAME barristers across the profession (13.6%), and the percentage of BAME QCs (8.1%). In particular, there is a greater disparity in the proportion of non-QCs from Black/Black British backgrounds compared to the proportion of QCs from the same background, with the disparity being particularly high for those of Black/Black British – African ethnic backgrounds. These figures may reflect the lower percentage of BAME barristers entering the profession in past years but may also suggest there may be an issue in the progression of BAME practitioners at the Bar. Read the full report here.

** Why the Bar needs to have a different conversation if we’re serious about recruiting more black judges: Dame Linda Dobbs QC spoke to Desiree Artesi about identifying new sources of potential, energising diversity efforts and coaxing out reluctant role models in the June 2019 issue of Counsel. Read it here.

‘I regard it as a duty which I owed, not just to my people, but also to my profession, to the practice of law, and to the justice for all mankind, to cry out against this discrimination which is essentially unjust and opposed to the whole basis of the attitude towards justice which is part of the tradition of legal training in this country. I believed that in taking up a stand against this injustice I was upholding the dignity of what should be an honourable profession.’

Nelson Mandela

The first thing I want to make clear is that I am not a race expert and do not profess to be one. I have some ideas just like the rest of you, and like some of you, I have given the subject of how to improve diversity and particularly racial diversity some deeper thought and consideration.

Until February 2020, I was joint head of Garden Court Chambers, the second largest set of chambers in the country and also a very diverse working environment. I am very proud to be a member of Garden Court and of its diversity; but even we do not rest on our laurels, and we recognise there is much improvement to be done in all areas of diversity within our chambers.

I often wonder whether the Bar is moving forward, standing still or moving backward. The recent Bar Standards Board (BSB) statistics on diversity are not encouraging. At times I really think we are moving backward. (I am a barrister member of the BSB, although this article is written in a personal capacity.)

In the last week, two important things for me have happened. Firstly, there has been a real discussion about race in the public discourse following the horrific killing of an unarmed black man, whose death was captured on video and we see him dying before our eyes and calling out for his dead mother. This has led us all to ask questions about race, discrimination, racism and how to be anti-racist and live and work in truly anti-racist ways. Secondly, I was appointed as the first black professor of law for the prestigious Gresham College, a free public university with a 400-year history of providing free education. The timing seems uncanny. It is important for me, given the work to which I have dedicated my life, to discuss recent events and what we can do to bring change to our society.

Racism and discriminatory behaviours pervade all levels of society and our legal system is not immune from the same. I have experienced it many times in my career. One judge said to me, ‘Mr Thomas, in this country we do things in this way…’ Anyone who knows me, knows that I speak with a South London accent, of which I’m proud. Which country did he think I came from? I know the judge would not say that to one of my colleagues. I was deliberately ‘othered’; made to feel different. My story is not unique. Many of my colleagues from the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) community have similar stories. Just think about it: if I can be treated in this way and I am a member of a well-respected profession, it takes very little imagination to think how black defendants are treated.

Differential treatment of black and brown people occurs at all levels in the legal system; differential and unfavourable treatment in encounters with police, decisions as to whether to charge or not, bail or not, in the way they are prosecuted, sentenced, type of sentence, length of sentence, treatment in prison, how they are disciplined in prison, parole decisions and so on.

The Lammy Review in 2017, which analysed the disproportionate treatment of BAME people in the criminal justice system, makes for depressing reading. Some of the statistics will come as no surprise to anyone who has been following the news, such as the fact that black people are six times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than white people. But it is not just the police that have a race problem. It is the judiciary. The Lammy Review showed that BAME defendants were 240% more likely to be given a prison sentence for a drug offence than white defendants. Black people make up 3% of the general population, but make up 12% of prisoners and 21% of children in custody. Every single one of those black prisoners, including those black children, was sent to prison by a judge. Interestingly, the Review also found, by contrast, that there is no evidence of racial bias in juries’ decisions to convict or acquit – suggesting that our judges have a bigger race problem than our juries do.

Nor is it just criminal courts that have a race problem. In the immigration system – a system which traces its modern roots to the profoundly racist Commonwealth Immigrants Acts 1962 and 1968 and Immigration Act 1971 – judges sit in judgment on BAME people every day. Some of these people are seeking asylum in the UK and have experienced horrific traumas in their home countries. Some are victims of human trafficking and similar abuses. Some are people who have lived here most of their lives, are British in all but name, and are now being ripped apart from their home, their family and their children because of a criminal conviction. Sadly, if not surprisingly, the attitudes of the people who administer this system today can at times be as racist and colonialist as those of the people who created it in the 1960s and 1970s. One barrister told me that a white immigration judge, having heard an appeal by a Somali appellant, commented on how refreshing it was to see a Somali family working. The same barrister, who is herself black, was told by a different judge that it was nice to see her ‘sitting on this side of the table’, pointing to the side of the table where counsel sit. Another judge told her at a training event that she did not have ‘negroid features’.

Granted these are anecdotal accounts, but until a profession-wide survey of the experiences of BAME legal professionals – akin to the ground-breaking Women at the Bar 2016 study by the BSB of their experience of the equality rules in practice – it is what we have. Take the trouble to ask a BAME colleague about their experiences in the law and you will build your own picture.

The BSB has a statutory regulatory objective to ‘encourage an independent, strong, diverse and effective legal profession’ under the Legal Services Act 2007 (LSA 2007). The BSB is bound by several regulatory objectives as set out in s 1 of the LSA 2007. Section 1(1)(c) of the Act specifies the regulatory objective of ‘improving access to justice’. While the ability of the general public to access justice via the legal profession is not wholly under the control of the legal regulators, the BSB seeks to make improvements where it has an influence. Section 1(1)(f) of the LSA 2007 sets out the regulatory objective of ‘encouraging an independent, strong, diverse and effective legal profession’. The BSB also has obligations under the Equality Act 2010.

The general duty requires public bodies, in the exercise of their functions, to pay due regard to the need to ‘eliminate unlawful discrimination, harassment, and victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by, or under, the Equality Act’ (Equality Act aim 1); to advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it (Equality Act aim 2); and foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it (Equality Act aim 3). The BSB has this legal duty. It is part of its regulatory role.

I recently said at a BSB meeting that there is a real problem in getting this message across to the profession. There is no doubt that many sectors, practice areas and chambers within our profession lack racial diversity. In these modern times, our websites shine a light on how diverse we are. Anyone – whether lay client, professional client or member of the public – can access the profiles and photographs of our members and the truth is laid bare.

The Diversity at the Bar 2019 statistics published in January 2020 make uncomfortable reading.* It has long been well known there is an under-representation of people of colour in the Chancery and commercial bar and in other specialist sectors. Why are there more people of colour in less lucrative and/or publicly funded areas such as crime?

Why is there still a gross under-representation of black judges? In 2020 there are still no black male High Court judges. We had one full-time black woman High Court judge in recent times who has since retired (Dame Linda Dobbs QC DBE was a High Court judge from 2004 to 2013**). There are no black Court of Appeal or Supreme Court judges.

As I said at the BSB meeting, the problem is one of messaging. If top commercial chambers are predominantly ‘white, male and older’, getting a message across to them of change is implicitly saying there is something fundamentally wrong with you. This is a difficult message to swallow. It is always difficult to change and challenge the status quo, particularly from the outside. There has to be a willingness to tackle this from within.

But some harsh realities need to be confronted. Firstly, to discuss diversity and improving diversity particularly as it concerns race, there needs to be a proper and honest discussion about racism. You see, it is possible to get to the top of our profession without ever discussing racism. It is not a job requirement to get to the top of our profession. It is possible to turn a blind eye to it. We can pretend if we don’t see it, it isn’t there. We can be comfortable with the status quo or the cards we have been dealt with. However, the reality is there for all to see – if we care to look. We as a profession have to move beyond seeing racism as individual characteristics. We need to understand racism as a system, not an event. None of us are exempt from its forces. Racism impacts differently on different groups. I often ask myself why a discussion on race is such a difficult subject.

It is a flawed and outdated view on racism to believe that the racist is an individual who consciously does not like people based on race and is intentionally mean to them. Such a definition is a deflection which protects the system. When our profession recognises that racism doesn’t necessarily come from individuals, doesn’t need to be conscious, and doesn’t need to be intentional, we will be moving in the right direction. Racial injustice and racism isn’t a simple binary question. The racist needn’t simply be bad, ignorant, bigoted, prejudiced or old. The non-racist isn’t necessarily the good person, educated, progressive, open or fair-minded, well-intended or young. This discussion goes well beyond this.

If you believe your chambers are ‘colour-blind’ and treat everyone the same, then you have a problem. That mindset is the problem. ‘Colour blindness’ does not work in a system where everyone at the top of judicial power is white, everyone in the ‘best’ chambers is white, and the two ‘best’ universities in the country have a lack of black entrants. If you are a person of colour, just seeing this would set alarm bells going. We cannot just take race off the table. It needs to be discussed.

Barristers are all unique and different. It is also a fact that the reasons for any of us doing this job are too numerous to be able to make assumptions or value judgments about. But regardless of what that driver is for you as to why you chose law, we all have a common purpose. A golden thread that unites us all. We all provide public service.

A question I am often asked is ‘Have you suffered discrimination, or felt the effect of racism in this profession?’’

How many white people here have been asked that particular question, based on their race? Do you believe that discrimination exists in society? If the answer is yes? So why would we assume that it does not exist within our profession? So the big question is how do we change and improve our profession?

I believe we have to change mindsets. We do that, I believe, by getting our profession to buy into why they should feel the need to change. Asking why is such a powerful question. If you understand the ‘why’ that is the key, for potentially long-lasting and effective change. So why should we want to change? Why should we make our profession more diverse? What’s in it for the profession? Because each individual will be saying silently to themselves. What is in it for me? Or what is in it for us?

Now let’s think about this. If you are one of the over-represented groups in the profession you are in a position of privilege and power, like it or not, and there is an obvious natural tendency to think of increased diversity as a decrease in ‘us’. Turkeys if they had a vote wouldn’t vote for Christmas.

But we want to get the profession to understand that potential clients or colleagues may come from different backgrounds; that the Bar needs to perform its duties in a way that acknowledges differences and the impact of discrimination on people we engage with. This comes back to the question posed above; do you think that there is discrimination in society? Should we be working towards eliminating systemic cultural and direct discrimination from the profession?

We should seek to ensure that we all contribute to a stronger, more culturally diverse Bar; that the profession does not discriminate in how it provides its service; and we should try to foster and encourage the profession to welcome the introduction of new diverse talent and give fair and equal opportunity based on merit to the lawyers already within this profession.

It will need to be a very powerful one because it is a normal thing to want to keep things as they are. But regardless of where you come from, or on which side of the divide you fall, or what your current demographic representation is in our profession, diversity benefits us all.

One of the best articles and arguments I’ve seen for diversity comes from one of a series of articles from a New Zealand lawyer and mediator Paul Sills. He goes further than the reasons we currently give. He argues the following:

Sills concludes that:

‘People who have grown up in multicultural societies often find it not only normal but desirable to live with people of different backgrounds. Diversity is not merely tolerated, but something to be actively sought out.’

Sills’ arguments are powerful and persuasive. We all have to embrace these arguments. It’s the job of our profession to acknowledge and present these arguments persuasively and convincingly.

This leads to less push back or reluctance. It overcomes the suggestion that this is just politically correct talk. But it is so much more than this.

White members of our profession need to understand that questioning the way things currently are is not about them being attacked, shamed, accused or judged. These are normal reactions and to be expected. But it is more a recognition that we as a profession can improve our lot; questions of being good or bad are irrelevant. It is a recognition that advantage may well be tied to race and that is systemic. We should forget the guilt and take action. History matters. Bias is implicit and often unconscious. More importantly, it takes great courage to change this system.

We are barristers. In our profession, we are problem solvers, solution finders, and deep thinkers. We are a profession with the greatest minds.

So let’s talk about race.

Postscript – I first penned this article before the brutal, horrific and heartless murder of George Floyd. This makes what I have to say even more relevant today. It was interesting to watch the hand wringing of people in our profession, as to whether they ought to put out statements condemning what they had seen, and whether they should support the statement ‘Black Lives Matter’. Some of the people wrestling with this ‘dilemma’ are well intentioned people. Some are professional colleagues I would describe as friends. However, in the words of the late MLK:

‘In the end we will remember not the words of our enemies but the silence of our friends.’

Martin Luther King Jr

* Diversity at the Bar 2019: The BSB report, published in January 2020, found that there is still a disparity between the overall percentage of BAME barristers across the profession (13.6%), and the percentage of BAME QCs (8.1%). In particular, there is a greater disparity in the proportion of non-QCs from Black/Black British backgrounds compared to the proportion of QCs from the same background, with the disparity being particularly high for those of Black/Black British – African ethnic backgrounds. These figures may reflect the lower percentage of BAME barristers entering the profession in past years but may also suggest there may be an issue in the progression of BAME practitioners at the Bar. Read the full report here.

** Why the Bar needs to have a different conversation if we’re serious about recruiting more black judges: Dame Linda Dobbs QC spoke to Desiree Artesi about identifying new sources of potential, energising diversity efforts and coaxing out reluctant role models in the June 2019 issue of Counsel. Read it here.

Let’s talk about race. Forget the guilt and take action. Bias is implicit and often unconscious. It takes great courage to change the system. It benefits us all. By Leslie Thomas QC, Gresham Professor of Law

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar