*/

There are two particular traits that judicial applicants can display repeatedly, and these can lead to inaccurate self-assessment. For those ready to be brutally honest with themselves, Manjula Bray sets out a five-step strategy to help plan for success

Over my 20 years of candidate assessment for senior appointments, half of that time has been spent supporting judicial applicants through the Law Society training I devised. Five years sitting as an independent assessor with the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) has given me unique insights and as a business psychologist, I’ve noticed two particular traits that legal applicants display repeatedly. I’ve written this piece to raise awareness of how preparation for judicial appointment is not a simple form-filling exercise.

The first trait is ‘imposter syndrome’. This is where an individual experiences feelings of inadequacy that persist despite evidence of past success. ‘Imposters’ suffer from chronic self-doubt and a sense of intellectual fraudulence that override any feelings of success or external proof of their competence. My positive action work with the Law Society has confirmed that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic applicants seem particularly prone to this one. However, I also believe that as a learned behaviour, it is feasible to unlearn it with the support of a coach.

The second trait frequently displayed in my judicial coachees is a sense of entitlement, or expectation that experience alone makes them eligible and competent to execute a judicial role. Perhaps you see people around you and wonder how on earth they were appointed? Or are you flummoxed as to why you or someone you hold in high regard were not appointed? Unfortunately, time served in any given role may imply but is not evidence of actual or potential qualities to appoint you in its merit-based competency selection exercise.

Both imposter and eligibility tendencies ultimately lead to an inaccurate self-assessment of the said individuals’ knowledge, skills and experience. This is inevitably reflected in their performance on paper and in person at selection day (usually half a day). For example, ‘imposters’ downplaying what they have to offer and the ‘entitled’ writing in an assumptive manner, and behaving like it’s a ‘done deal’.

The JAC uses the competency based method to both assess candidates for recruitment purposes as well as for appraising performance (both fee-paid and salaried positions). The following five core competencies or behaviours are applicable judiciary-wide:

1. exercising judgment;

2. possessing and building knowledge;

3. assimilating and clarifying information;

4. working and communicating with others; and

5. managing work efficiently

I work with ‘competent contenders’ who have a grasp on their own reality, ie barristers and solicitors who are prepared to hold up the mirror to themselves and be brutally honest, and brave enough to solicit feedback as well as acknowledge their accomplishments. Competent contenders also possess ‘emotional intelligence’ (or EQ) and a ‘growth mindset’. So, if you are prepared to work on yourself first, then the practical preparation that follows will aid your future success.

It all starts with evidence. You will need a pad of sticky notes and a pen...

1. Find a place and time to reflect: A weekend is perhaps better than straight after a full day of work. Recall the more impactful achievements you’ve experienced – in your professional life primarily – ie when you felt you were at the top of your game (non-work examples could also provide valid evidence).

Consider also when others recognised or commended you for exceptional achievements.

2. Note each of these critical occasions on separate sticky notes: Limit yourself to just one occasion per note and give each one a short title which will prompt your memory to recall that moment vividly.

Repeat this process until you have recalled around 10 of these positive Critical Incidents (CIs). Try to choose CIs where:

(a) a positive conclusion or outcome has already been reached; and

(b) you are the protagonist in the story.

3. Evaluate the strength of your examples: For judicial appointments in England and Wales refer to the specific JAC prompts for each competency (see ‘Choosing the best examples in your self-assessment’: bit.ly/3iZTLsx).

For other vacancies, get some support and feedback from a mentor or trusted adviser regarding the strength of your selected examples of achievement.

Once you have generated sufficient examples, double check that you are really sure that this represents your best (as in your proudest) material. The following ‘SIR’ acronym questions will hopefully keep you on track:

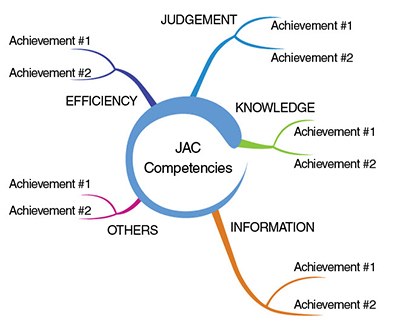

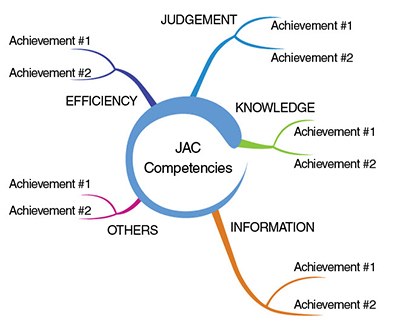

4. Next, attach your sticky notes to a large JAC competency mind map (a piece of flip chart paper is ideal) to ascertain where there are gaps in your evidence – you should aim for a couple of examples of achievement under each competency:

5. Finally, draft each of your achievements in the JAC recommended ‘SOAR’ structure:

Aim to write a couple of examples for each of the five competency headings under the published competency framework for a vacancy… while simultaneously addressing the content of the job description. It’s important to be succinct!

Being invited to sit a qualifying test does not necessarily mean that your application form was good enough to get you through to the later stages in the selection process. Your self-assessment is invariably not read until prior to interview (unless the sift was conducted in the absence of a qualifying test – as is often the case for salaried roles) so it is vital that you are thorough and robust in compiling the competency sections of your online application.

I highly recommend you also continue to write up new examples on an ongoing basis and that you refrain from word count culling until the very end (the online application form will simply delete any words over the 250 limit under each competency section).

There is so much more I could share, such as how to identify and support your independent assessors, how to deliver your best achievements at interview, and tips for the role play. In the meantime, I hope this article sets you on a positive path to evidencing all the competencies competently for the judicial appointment you seek.

Over my 20 years of candidate assessment for senior appointments, half of that time has been spent supporting judicial applicants through the Law Society training I devised. Five years sitting as an independent assessor with the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) has given me unique insights and as a business psychologist, I’ve noticed two particular traits that legal applicants display repeatedly. I’ve written this piece to raise awareness of how preparation for judicial appointment is not a simple form-filling exercise.

The first trait is ‘imposter syndrome’. This is where an individual experiences feelings of inadequacy that persist despite evidence of past success. ‘Imposters’ suffer from chronic self-doubt and a sense of intellectual fraudulence that override any feelings of success or external proof of their competence. My positive action work with the Law Society has confirmed that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic applicants seem particularly prone to this one. However, I also believe that as a learned behaviour, it is feasible to unlearn it with the support of a coach.

The second trait frequently displayed in my judicial coachees is a sense of entitlement, or expectation that experience alone makes them eligible and competent to execute a judicial role. Perhaps you see people around you and wonder how on earth they were appointed? Or are you flummoxed as to why you or someone you hold in high regard were not appointed? Unfortunately, time served in any given role may imply but is not evidence of actual or potential qualities to appoint you in its merit-based competency selection exercise.

Both imposter and eligibility tendencies ultimately lead to an inaccurate self-assessment of the said individuals’ knowledge, skills and experience. This is inevitably reflected in their performance on paper and in person at selection day (usually half a day). For example, ‘imposters’ downplaying what they have to offer and the ‘entitled’ writing in an assumptive manner, and behaving like it’s a ‘done deal’.

The JAC uses the competency based method to both assess candidates for recruitment purposes as well as for appraising performance (both fee-paid and salaried positions). The following five core competencies or behaviours are applicable judiciary-wide:

1. exercising judgment;

2. possessing and building knowledge;

3. assimilating and clarifying information;

4. working and communicating with others; and

5. managing work efficiently

I work with ‘competent contenders’ who have a grasp on their own reality, ie barristers and solicitors who are prepared to hold up the mirror to themselves and be brutally honest, and brave enough to solicit feedback as well as acknowledge their accomplishments. Competent contenders also possess ‘emotional intelligence’ (or EQ) and a ‘growth mindset’. So, if you are prepared to work on yourself first, then the practical preparation that follows will aid your future success.

It all starts with evidence. You will need a pad of sticky notes and a pen...

1. Find a place and time to reflect: A weekend is perhaps better than straight after a full day of work. Recall the more impactful achievements you’ve experienced – in your professional life primarily – ie when you felt you were at the top of your game (non-work examples could also provide valid evidence).

Consider also when others recognised or commended you for exceptional achievements.

2. Note each of these critical occasions on separate sticky notes: Limit yourself to just one occasion per note and give each one a short title which will prompt your memory to recall that moment vividly.

Repeat this process until you have recalled around 10 of these positive Critical Incidents (CIs). Try to choose CIs where:

(a) a positive conclusion or outcome has already been reached; and

(b) you are the protagonist in the story.

3. Evaluate the strength of your examples: For judicial appointments in England and Wales refer to the specific JAC prompts for each competency (see ‘Choosing the best examples in your self-assessment’: bit.ly/3iZTLsx).

For other vacancies, get some support and feedback from a mentor or trusted adviser regarding the strength of your selected examples of achievement.

Once you have generated sufficient examples, double check that you are really sure that this represents your best (as in your proudest) material. The following ‘SIR’ acronym questions will hopefully keep you on track:

4. Next, attach your sticky notes to a large JAC competency mind map (a piece of flip chart paper is ideal) to ascertain where there are gaps in your evidence – you should aim for a couple of examples of achievement under each competency:

5. Finally, draft each of your achievements in the JAC recommended ‘SOAR’ structure:

Aim to write a couple of examples for each of the five competency headings under the published competency framework for a vacancy… while simultaneously addressing the content of the job description. It’s important to be succinct!

Being invited to sit a qualifying test does not necessarily mean that your application form was good enough to get you through to the later stages in the selection process. Your self-assessment is invariably not read until prior to interview (unless the sift was conducted in the absence of a qualifying test – as is often the case for salaried roles) so it is vital that you are thorough and robust in compiling the competency sections of your online application.

I highly recommend you also continue to write up new examples on an ongoing basis and that you refrain from word count culling until the very end (the online application form will simply delete any words over the 250 limit under each competency section).

There is so much more I could share, such as how to identify and support your independent assessors, how to deliver your best achievements at interview, and tips for the role play. In the meantime, I hope this article sets you on a positive path to evidencing all the competencies competently for the judicial appointment you seek.

There are two particular traits that judicial applicants can display repeatedly, and these can lead to inaccurate self-assessment. For those ready to be brutally honest with themselves, Manjula Bray sets out a five-step strategy to help plan for success

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar