*/

.jpg?sfvrsn=2d8ac7fe_1)

The appointment of King’s Counsel (KC) represents one of the most significant milestones in a barrister’s career. Yet, for many disabled barristers, structural and procedural barriers remain deeply embedded in the selection process. While formal equality duties exist in law, the interplay of evaluation mechanisms, practical adjustments, and institutional culture create complex obstacles that demand scrutiny.

King’s Counsel Appointments (KCA) operates under a framework of legal duties, including:

In March 2023, I submitted my second KC application. Despite the legal protections above, my experience exposes critical concerns regarding the process’s responsiveness to disability-related barriers.

A central distinction requires emphasis. The KCA Secretariat administers logistical adjustments (e.g., extending deadlines or modifying interview formats), while substantive evaluation rests with the independent Selection Panel. This separation is clear in the KCA’s own Guidance for Applicants. While the Secretariat generally accommodated my scheduling needs, the evaluation process itself failed to recognise how disabilities may limit opportunities to gather traditional forms of evidence (such as extensive third-party assessors) and courtroom experience.

In my case, I had disclosed under Section G the impact of my disability, which significantly restricts in-person court appearances and opportunities to conduct advocacy in complex hearings before High Court and appellate tribunals. Consequently, securing the standard volume of judicial, professional and client assessments becomes disproportionately difficult for disabled applicants. The KCA’s focus on ‘compelling evidence of excellence’ disproportionately disadvantages applicants whose impairments preclude traditional evidence-gathering opportunities.

In early 2024, I submitted detailed enquiries to KCA, seeking clarification on how Section G disclosures interact with the evaluation of evidence. Specifically, I asked:

The KCA declined to substantively answer these enquiries, asserting in July 2024 that it had fulfilled its Equality Act duties but declining further engagement. My subject access request was similarly refused, and this position was ultimately upheld by the Information Commissioner’s Office in March 2025.

The Bar Standards Board (BSB), which regulates barristers but not KCA, acknowledged its lack of jurisdiction. BSB Director Mark Neale encouraged dialogue with the Bar Council’s current Disability Panel, chaired by Mark Henderson, but no engagement has been pursued by me due to my own previous disappointing experience of the Bar Council’s (old) Disability Sub-Committee (of which I was a member for approximately ten years).

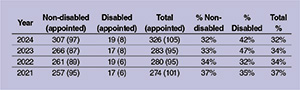

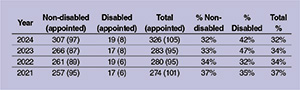

KCA’s supplied data for 2021-24 indicate, at face value, that disabled applicants* who reach application stage have a higher success rate than non-disabled applicants:

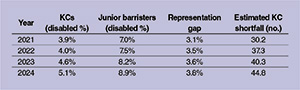

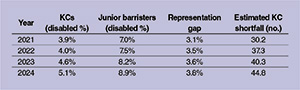

However, the BSB’s broader data (Diversity at the Bar 2024) demonstrates a growing representational gap at senior levels:

While disabled juniors comprise nearly 9% of the Bar, only 5.1% of KCs declare a disability. This suggests that systemic barriers disproportionately operate before application – in opportunities to gain KC-qualifying experience – rather than at the final evaluation stage alone. As Sir Paul Morgan, outgoing member of the KC Selection Panel noted in an article for this magazine: ‘the pool of eligible candidates is inevitably shaped by prior career pathways’ (Counsel 2025).

The Social Change Agency’s March 2024 report for the Legal Services Board (LSB), Mapping Systemic Barriers to Equality Diversity and Inclusion in the Legal Professions (SCA 2024) and the LSB’s own 2021 report Reshaping Legal Services (LSB 2021) both highlight structural disadvantage in legal career progression. These reports identify:

While some suggest that disabled barristers might substitute pro bono or tribunal work to build advocacy records, this oversimplifies reality. Such work may lack the complex interlocutory, appellate and multi-day hearings necessary to fulfil KC competency criteria. Moreover, many tribunal settings involve written advocacy, remote hearings or low-value claims less likely to yield judicial assessors meeting the KCA’s evidentiary standards.

If the appointments system is to become substantively inclusive, the following merit serious consideration:

The profession rightly celebrates progress in widening access to the junior Bar. Yet the persistent shortfall in disabled representation at the KC level reflects systemic challenges embedded across career development stages, not simply in final appointment decisions. Without bolder structural reforms, the risk remains that the King’s Counsel ladder remains, in practice, one which only certain bodies can climb.

This is not grievance; it is constitutional fairness.

‘KCA’s processes are independently audited. We continue to increase awareness and improve transparency through our outreach work for both applicants and assessors. Further details can be found on our website.’

* KCA’s statistics reflect applicants who self-identify as disabled, without disclosing methodology, type of disability or demographic context.

References

King’s Counsel Appointments: Guidance for applicants, 2024

Disability at the Bar 2024, Bar Standards Board, 2025

Mapping Systemic Barriers to Equality Diversity and Inclusion in the Legal Professions, Social Change Agency, 2024

Reshaping Legal Services, Legal Services Board, 2021

Legally Disabled? The impact of Covid-19 on the employment and training of disabled lawyers in England and Wales: opportunities for job-redesign and best practice, Prof Debbie Foster and Dr Natasha Hirst, 2020: legallydisabled.com

‘Doing diversity in the legal profession in England and Wales: why do disabled people continue to be unexpected?’ Prof Debbie Foster and Dr Natasha Hirst, Journal of Law and Society, 49(3), 2022

‘KC selection: a view from the inside’, Sir Paul Morgan, Counsel, February 2025

.jpg?sfvrsn=2d8ac7fe_1)

The appointment of King’s Counsel (KC) represents one of the most significant milestones in a barrister’s career. Yet, for many disabled barristers, structural and procedural barriers remain deeply embedded in the selection process. While formal equality duties exist in law, the interplay of evaluation mechanisms, practical adjustments, and institutional culture create complex obstacles that demand scrutiny.

King’s Counsel Appointments (KCA) operates under a framework of legal duties, including:

In March 2023, I submitted my second KC application. Despite the legal protections above, my experience exposes critical concerns regarding the process’s responsiveness to disability-related barriers.

A central distinction requires emphasis. The KCA Secretariat administers logistical adjustments (e.g., extending deadlines or modifying interview formats), while substantive evaluation rests with the independent Selection Panel. This separation is clear in the KCA’s own Guidance for Applicants. While the Secretariat generally accommodated my scheduling needs, the evaluation process itself failed to recognise how disabilities may limit opportunities to gather traditional forms of evidence (such as extensive third-party assessors) and courtroom experience.

In my case, I had disclosed under Section G the impact of my disability, which significantly restricts in-person court appearances and opportunities to conduct advocacy in complex hearings before High Court and appellate tribunals. Consequently, securing the standard volume of judicial, professional and client assessments becomes disproportionately difficult for disabled applicants. The KCA’s focus on ‘compelling evidence of excellence’ disproportionately disadvantages applicants whose impairments preclude traditional evidence-gathering opportunities.

In early 2024, I submitted detailed enquiries to KCA, seeking clarification on how Section G disclosures interact with the evaluation of evidence. Specifically, I asked:

The KCA declined to substantively answer these enquiries, asserting in July 2024 that it had fulfilled its Equality Act duties but declining further engagement. My subject access request was similarly refused, and this position was ultimately upheld by the Information Commissioner’s Office in March 2025.

The Bar Standards Board (BSB), which regulates barristers but not KCA, acknowledged its lack of jurisdiction. BSB Director Mark Neale encouraged dialogue with the Bar Council’s current Disability Panel, chaired by Mark Henderson, but no engagement has been pursued by me due to my own previous disappointing experience of the Bar Council’s (old) Disability Sub-Committee (of which I was a member for approximately ten years).

KCA’s supplied data for 2021-24 indicate, at face value, that disabled applicants* who reach application stage have a higher success rate than non-disabled applicants:

However, the BSB’s broader data (Diversity at the Bar 2024) demonstrates a growing representational gap at senior levels:

While disabled juniors comprise nearly 9% of the Bar, only 5.1% of KCs declare a disability. This suggests that systemic barriers disproportionately operate before application – in opportunities to gain KC-qualifying experience – rather than at the final evaluation stage alone. As Sir Paul Morgan, outgoing member of the KC Selection Panel noted in an article for this magazine: ‘the pool of eligible candidates is inevitably shaped by prior career pathways’ (Counsel 2025).

The Social Change Agency’s March 2024 report for the Legal Services Board (LSB), Mapping Systemic Barriers to Equality Diversity and Inclusion in the Legal Professions (SCA 2024) and the LSB’s own 2021 report Reshaping Legal Services (LSB 2021) both highlight structural disadvantage in legal career progression. These reports identify:

While some suggest that disabled barristers might substitute pro bono or tribunal work to build advocacy records, this oversimplifies reality. Such work may lack the complex interlocutory, appellate and multi-day hearings necessary to fulfil KC competency criteria. Moreover, many tribunal settings involve written advocacy, remote hearings or low-value claims less likely to yield judicial assessors meeting the KCA’s evidentiary standards.

If the appointments system is to become substantively inclusive, the following merit serious consideration:

The profession rightly celebrates progress in widening access to the junior Bar. Yet the persistent shortfall in disabled representation at the KC level reflects systemic challenges embedded across career development stages, not simply in final appointment decisions. Without bolder structural reforms, the risk remains that the King’s Counsel ladder remains, in practice, one which only certain bodies can climb.

This is not grievance; it is constitutional fairness.

‘KCA’s processes are independently audited. We continue to increase awareness and improve transparency through our outreach work for both applicants and assessors. Further details can be found on our website.’

* KCA’s statistics reflect applicants who self-identify as disabled, without disclosing methodology, type of disability or demographic context.

References

King’s Counsel Appointments: Guidance for applicants, 2024

Disability at the Bar 2024, Bar Standards Board, 2025

Mapping Systemic Barriers to Equality Diversity and Inclusion in the Legal Professions, Social Change Agency, 2024

Reshaping Legal Services, Legal Services Board, 2021

Legally Disabled? The impact of Covid-19 on the employment and training of disabled lawyers in England and Wales: opportunities for job-redesign and best practice, Prof Debbie Foster and Dr Natasha Hirst, 2020: legallydisabled.com

‘Doing diversity in the legal profession in England and Wales: why do disabled people continue to be unexpected?’ Prof Debbie Foster and Dr Natasha Hirst, Journal of Law and Society, 49(3), 2022

‘KC selection: a view from the inside’, Sir Paul Morgan, Counsel, February 2025

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar