*/

In my 22 years as a barristers’ clerk, I have witnessed the evolution of the Bar in many respects; the shift towards direct access, advancements in the use of technology such as electronic hearing bundles which have streamlined case management, reducing reliance on physical documents and marking the end of the traditional and iconic pink tape, and the move to more remote hearings allowing for greater flexibility and efficiency in legal proceedings.

However, in my opinion, the most profound evolution may be in the cultural dynamics between clerks and barristers. Unspoken codes and the legacy of the clerks’ room were passed down through generations. While my early experience was a positive one, the evolution towards a more modern, inclusive clerks’ room, coupled with a shift in attitudes towards regulations and fairness, has undoubtedly contributed to better functioning clerks’ rooms and improved relationships with barristers.

To understand the evolution of these relationships one must consider the relatively recent history of the clerking profession. Thirty years ago, clerks in London chambers were predominately male and from a specific social and cultural background. Part of the profession relied to a significant extent on nepotism and favoritism for recruitment at entry level, with roles often filled immediately by candidates who arrived in the clerks’ room immediately after secondary education, and usually within a narrow demographic. The route into clerking was often via someone you knew already working in a set or another chambers, i.e., grandfather, father, uncle, brother, cousin, or close friend.

Entering the clerking profession at junior level today via nepotism, or favoritism, probably so seldom appears to happen that one could say in practical terms those routes no longer exist. The shift in recruitment at an entry level now has been one from a field that was once dominated by personal connections, to one that is now based on value, merit and skill. I consider that the demanding roles and responsibilities of modern clerks require possession of specific traits and qualities in order to excel, and in today’s world nepotism cannot save a clerk who is not performing to the level of competence required in modern sets.

This evolution was imperative, and the first significant step, towards introducing diversity into clerks’ rooms. When we speak of diversity, it is not just about cultural background – it is about ensuring that there is a healthy male to female ratio. Increased female representation was the second step. Women have been historically underrepresented in this profession, with women once relegated to support roles such as chambers housekeeper, secretary, typist and receptionist – which is where I started. This gender imbalance is improving, and it is encouraging to see so many more women fulfilling roles historically occupied by men only.

Accomplishing the third step – increased representation by clerks with an ethnic minority background – has required recruitment to become more transparent and widespread. By advertising more broadly and outside the traditional channels, recruitment agencies help to demystify the clerking profession and has, in my view, led to chambers having access to a more diverse range of qualified applicants from which to recruit. This approach not only enriches the profession by drawing on a variety of cultural backgrounds, but also ensures that talent and passion are the primary criteria for recruitment.

Another important step driving greater diversity in the clerks’ room is the changing nature of the relationship between a senior clerk and their barrister. This traditional bond, once seen as an exclusive and almost sacred connection, has transformed into a more inclusive relationship. It is more common for there to be close working relationships between clerks of varying levels of seniority and all barristers, regardless of their own seniority. The sense of camaraderie and unity that now includes more junior clerks is a significant step towards a more modern and dynamic clerks’ room. It allows for a flow of ideas and support that can only benefit chambers and its members.

The combination of these steps reflects a comprehensive approach to creating a genuinely diverse clerks’ room. Achieving this is crucial to produce good business outcomes for chambers, to reflect the contemporary society in which we operate, and to foster an inclusive environment for members of chambers, members of staff and pupil barristers where everyone, regardless of their background, feels welcome and supported.

The challenges that some female barristers have experienced in practice often went unspoken in previous eras. I believe one reason for this was that female barristers did not want to be perceived as weaker, in any context, to their male counterparts. While I am aware some women have no inhibitions about sharing their professional and other concerns with male clerks, it is likely that the greater opportunities now to seek non-judgemental support and empathetic communication from female clerks in chambers is something many female barristers welcome. It is undeniable that female clerks play a vital role to being felt heard and that they provide support and understanding on issues uniquely affecting women. This communication process should also mean that increasing numbers of male clerks will be more attuned to some of these particular issues and concerns when raised by female members of chambers.

When sets advertise for pupil barristers or seek to recruit established practitioners, maintaining and improving levels of diversity is often an increasingly important consideration. One will often encounter advertisements expressly encouraging applications from female, ethnic minority, disabled, and/or socially mobile candidates.

Diverse representation within the membership of chambers and staff can play an important role in ensuring that barristers from diverse ethnic backgrounds and other underrepresented groups have confidence in the operation and leadership of their chambers. Barristers trust their clerks with their practice, including work allocation, fee quoting, and support for career progression. The clerks’ room is often referred to as the engine room of chambers; the decisions we make impact materially on barristers’ daily working lives; a diverse clerks’ room helps to ensure that these decisions are more likely to be made in an informed manner, with sensitivity and cultural awareness.

Diverse representation also provides visible role models for future clerks and aspiring barristers. Pupils seek mentorship, guidance and a supportive environment, and these role models demonstrate that success is attainable regardless of ethnicity, gender, disability or other underrepresented protected characteristics.

As clerks we connect with lay people, solicitors and barristers from all walks of life. We must be creative, reassuring, and confident – we are keen problem-solvers. We seek to instil the feeling of being valued, empowered, and to show respect for the cultural differences of those we encounter. In understanding those differences, it allows us to understand our clients’ needs and preferences better and contributes to establishing and fostering good relations between them and our barristers.

Leadership plays a crucial role in setting the tone for workplace culture, including attitudes towards equality and bias. Research shows that inclusive leadership is key to creating an environment where everyone feels valued and respected. See, for example, ‘The benefits of inclusive leadership’, Korn Ferry. Based on my own experiences, I firmly believe that it is one’s individual skill set, an open mind, awareness, compassion and empathy that help to create an inclusive environment, not merely one’s cultural heritage. I would like to think my role and the positive atmosphere for members and staff we cultivate at New Square Chambers are proof of that.

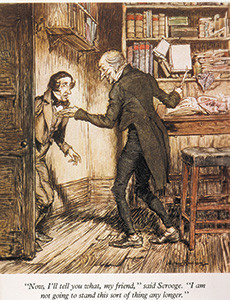

The changing nature of barrister-clerk relationship has been an important step in driving diversity. In Victorian times, the role of barristers’ clerk is thought to be similar to that of Bob Cratchit (pictured above) in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Today, it has transformed into a more inclusive relationship.

In my 22 years as a barristers’ clerk, I have witnessed the evolution of the Bar in many respects; the shift towards direct access, advancements in the use of technology such as electronic hearing bundles which have streamlined case management, reducing reliance on physical documents and marking the end of the traditional and iconic pink tape, and the move to more remote hearings allowing for greater flexibility and efficiency in legal proceedings.

However, in my opinion, the most profound evolution may be in the cultural dynamics between clerks and barristers. Unspoken codes and the legacy of the clerks’ room were passed down through generations. While my early experience was a positive one, the evolution towards a more modern, inclusive clerks’ room, coupled with a shift in attitudes towards regulations and fairness, has undoubtedly contributed to better functioning clerks’ rooms and improved relationships with barristers.

To understand the evolution of these relationships one must consider the relatively recent history of the clerking profession. Thirty years ago, clerks in London chambers were predominately male and from a specific social and cultural background. Part of the profession relied to a significant extent on nepotism and favoritism for recruitment at entry level, with roles often filled immediately by candidates who arrived in the clerks’ room immediately after secondary education, and usually within a narrow demographic. The route into clerking was often via someone you knew already working in a set or another chambers, i.e., grandfather, father, uncle, brother, cousin, or close friend.

Entering the clerking profession at junior level today via nepotism, or favoritism, probably so seldom appears to happen that one could say in practical terms those routes no longer exist. The shift in recruitment at an entry level now has been one from a field that was once dominated by personal connections, to one that is now based on value, merit and skill. I consider that the demanding roles and responsibilities of modern clerks require possession of specific traits and qualities in order to excel, and in today’s world nepotism cannot save a clerk who is not performing to the level of competence required in modern sets.

This evolution was imperative, and the first significant step, towards introducing diversity into clerks’ rooms. When we speak of diversity, it is not just about cultural background – it is about ensuring that there is a healthy male to female ratio. Increased female representation was the second step. Women have been historically underrepresented in this profession, with women once relegated to support roles such as chambers housekeeper, secretary, typist and receptionist – which is where I started. This gender imbalance is improving, and it is encouraging to see so many more women fulfilling roles historically occupied by men only.

Accomplishing the third step – increased representation by clerks with an ethnic minority background – has required recruitment to become more transparent and widespread. By advertising more broadly and outside the traditional channels, recruitment agencies help to demystify the clerking profession and has, in my view, led to chambers having access to a more diverse range of qualified applicants from which to recruit. This approach not only enriches the profession by drawing on a variety of cultural backgrounds, but also ensures that talent and passion are the primary criteria for recruitment.

Another important step driving greater diversity in the clerks’ room is the changing nature of the relationship between a senior clerk and their barrister. This traditional bond, once seen as an exclusive and almost sacred connection, has transformed into a more inclusive relationship. It is more common for there to be close working relationships between clerks of varying levels of seniority and all barristers, regardless of their own seniority. The sense of camaraderie and unity that now includes more junior clerks is a significant step towards a more modern and dynamic clerks’ room. It allows for a flow of ideas and support that can only benefit chambers and its members.

The combination of these steps reflects a comprehensive approach to creating a genuinely diverse clerks’ room. Achieving this is crucial to produce good business outcomes for chambers, to reflect the contemporary society in which we operate, and to foster an inclusive environment for members of chambers, members of staff and pupil barristers where everyone, regardless of their background, feels welcome and supported.

The challenges that some female barristers have experienced in practice often went unspoken in previous eras. I believe one reason for this was that female barristers did not want to be perceived as weaker, in any context, to their male counterparts. While I am aware some women have no inhibitions about sharing their professional and other concerns with male clerks, it is likely that the greater opportunities now to seek non-judgemental support and empathetic communication from female clerks in chambers is something many female barristers welcome. It is undeniable that female clerks play a vital role to being felt heard and that they provide support and understanding on issues uniquely affecting women. This communication process should also mean that increasing numbers of male clerks will be more attuned to some of these particular issues and concerns when raised by female members of chambers.

When sets advertise for pupil barristers or seek to recruit established practitioners, maintaining and improving levels of diversity is often an increasingly important consideration. One will often encounter advertisements expressly encouraging applications from female, ethnic minority, disabled, and/or socially mobile candidates.

Diverse representation within the membership of chambers and staff can play an important role in ensuring that barristers from diverse ethnic backgrounds and other underrepresented groups have confidence in the operation and leadership of their chambers. Barristers trust their clerks with their practice, including work allocation, fee quoting, and support for career progression. The clerks’ room is often referred to as the engine room of chambers; the decisions we make impact materially on barristers’ daily working lives; a diverse clerks’ room helps to ensure that these decisions are more likely to be made in an informed manner, with sensitivity and cultural awareness.

Diverse representation also provides visible role models for future clerks and aspiring barristers. Pupils seek mentorship, guidance and a supportive environment, and these role models demonstrate that success is attainable regardless of ethnicity, gender, disability or other underrepresented protected characteristics.

As clerks we connect with lay people, solicitors and barristers from all walks of life. We must be creative, reassuring, and confident – we are keen problem-solvers. We seek to instil the feeling of being valued, empowered, and to show respect for the cultural differences of those we encounter. In understanding those differences, it allows us to understand our clients’ needs and preferences better and contributes to establishing and fostering good relations between them and our barristers.

Leadership plays a crucial role in setting the tone for workplace culture, including attitudes towards equality and bias. Research shows that inclusive leadership is key to creating an environment where everyone feels valued and respected. See, for example, ‘The benefits of inclusive leadership’, Korn Ferry. Based on my own experiences, I firmly believe that it is one’s individual skill set, an open mind, awareness, compassion and empathy that help to create an inclusive environment, not merely one’s cultural heritage. I would like to think my role and the positive atmosphere for members and staff we cultivate at New Square Chambers are proof of that.

The changing nature of barrister-clerk relationship has been an important step in driving diversity. In Victorian times, the role of barristers’ clerk is thought to be similar to that of Bob Cratchit (pictured above) in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Today, it has transformed into a more inclusive relationship.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar