*/

Oliver Hanmer outlines the regulator’s new measures to improve standards in youth court advocacy

No one could argue against the notion that every child deserves the very best chance in life.

But what happens when that child ends up accused of a serious crime and finds themselves caught up in the daunting world of the justice system? It can be difficult enough for some adults, let alone for children who may also have mental health issues, learning and communication difficulties and/or troubled backgrounds.

It is for these important reasons that I would like to explain the Bar Standards Board’s (BSB) recent policy announcements in this area. These are designed to highlight the specialist nature of advocacy within youth proceedings and to drive up the standards of representation for the young people concerned.

In recent years, there has been a lot of focus on the experiences of young people in youth proceedings. Lord Carlile of Berriew CBE QC chaired the Inquiry into the Operation and Effectiveness of the Youth Court, which published its findings in June 2014.

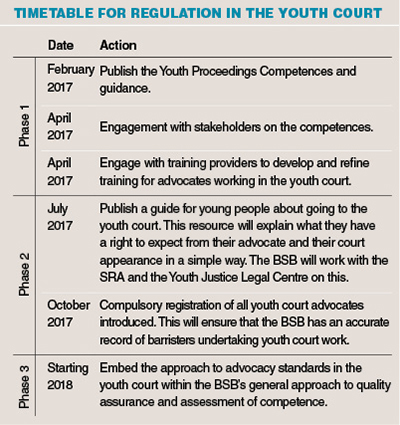

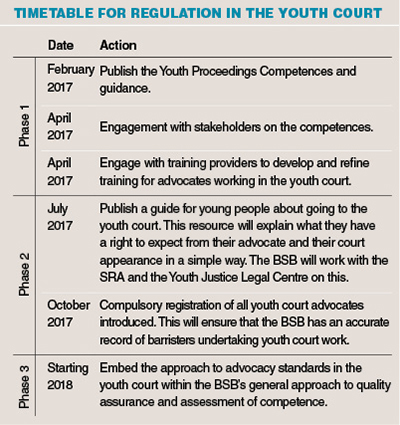

In October 2014 the BSB, along with CILEx Regulation, commissioned a review into the standards of advocacy in youth proceedings. Our review found that advocacy standards in youth proceedings were mixed. While there were examples of good practice, young defendants could not be assured of getting competent representation every time. The package of measures that we announced recently, and which are explained in this article, have been developed directly from the evidence that we obtained from our comprehensive review.

The main focus of our review was the work of barristers and chartered legal executive advocates. The Solicitors Regulation Authority has also developed its own youth court specialist support package for solicitors.

In December 2016, we welcomed the Ministry of Justice’s review by Charlie Taylor into youth justice. It made 36 recommendations to improve the youth justice system including placing a strong emphasis on the importance of high standards of advocacy.

As a public interest regulator, I believe this is exactly the type of area in which we should be focusing our attention. That’s not because we want to be critical of barristers operating in this field—far from it, in fact. But because we think more should be done to support them. One of the ways that we can do this is to call for greater value to be placed on youth proceedings advocacy, both by the profession as a whole and also by the Ministry of Justice.

We think it is wrong that this work is underfunded by the public purse. Increasingly, more and more serious cases are being heard in the youth court—cases that can have devastating long-term effects for the young people involved, especially if their experience of the justice system is negative.

One of the consequences of this underfunding is that it is often seen by the profession as a way for junior barristers to 'cut their teeth'. We think this is wrong as well. We think youth work should be seen as a specialist area of practice. And that practitioners should be supported with appropriate training and encouraged to deliver consistently the unique competences required when representing young people.

Because we believe this is all in the best interests of young people, we recently announced a package of measures to address these issues.

Our approach is to ensure that youth court barristers are equipped with the knowledge, skills and attributes needed to provide competent representation. These are set out in our recently published Youth Proceedings Competences document. It outlines the key competences that barristers who undertake youth proceedings must meet, along with some supporting guidance about how to meet those competences. The competences themselves have been developed collaboratively with organisations across the youth justice sector. They include specialist requirements in the following areas:

Later in the year, we will be introducing compulsory registration for barristers practising in youth advocacy. Registration will allow us to identify all barristers who represent young people and to ensure that they can demonstrate the specialist knowledge, skills and attributes set out in the competences document.

We do not intend to take a heavy handed approach to our regulation in this area. We want to work alongside registered youth practitioners to help them develop these competences over time through training and CPD.

We are aware that there have been arguments to make training for advocates in the youth court compulsory. As we want to regulate proportionately, we do not currently intend to make training compulsory. This is because we are mindful that for now, youth court work tends to be lower paid and we do not want to discourage barristers away from this work. We will gather evidence on the impact our regulation is having and revise our approach if standards are not improving.

We are also working with charity legal service providers, such as Just for Kids Law's Youth Justice Legal Centre, and other legal regulators to ensure that there is competent representation no matter whether the legal representative is a barrister, solicitor-advocate or chartered legal executive. We will also continue to work with the Youth Justice Board, the judiciary and youth offending teams to raise awareness of our competences and their impact on advocacy standards. The engagement of stakeholders from across the sector is invaluable on such an important agenda, so we are particularly pleased to be attending the Youth Justice Summit run by the Youth Justice Legal Centre on 12 May 2017.

Young people's needs may be complex and challenging, but that does not mean they do not have the same rights as anyone else to access to justice.

Contributor Oliver Hanmer, BSB Director of Regulatory Assurance

Case study: advocacy in the youth court

Juwon was 16 years old when he was arrested after being found asleep in a flat that had been broken into. He was charged with burglary and bailed to appear at a youth court. At court he was polite, answered questions when asked, and agreed with the police statements. On this basis he was advised to plead guilty.

The court heard he was in school and hoped to become a plumber. He was apologetic and remorseful. As he was automatically eligible for a referral order the hearing lasted a few minutes.

In the weeks that followed the Youth Offending Team (YOT) discovered Juwon was homeless. He had been living with his uncle and aunt; shortly before the burglary allegation, Juwon's uncle had died unexpectedly. Juwon was very close to his uncle and struggled to come to terms with his death. On the night of his arrest, Juwon had been drinking heavily and has no memory of how he came to be in the flat. His aunt was understandably upset at Juwon's behaviour and lack of respect, so cut all ties with him; leaving his belongings in black bags outside her home and refusing to come to the police station or court.

Juwon did not volunteer any of this. A barrister with youth justice expertise would have known the importance of finding out background information and it is highly likely the Crown Prosecution Service would have reviewed its decision to prosecute. Regrettably, Juwon now has a criminal record for an offence of domestic burglary. This is likely to prove a barrier to his career aspirations.

But what happens when that child ends up accused of a serious crime and finds themselves caught up in the daunting world of the justice system? It can be difficult enough for some adults, let alone for children who may also have mental health issues, learning and communication difficulties and/or troubled backgrounds.

It is for these important reasons that I would like to explain the Bar Standards Board’s (BSB) recent policy announcements in this area. These are designed to highlight the specialist nature of advocacy within youth proceedings and to drive up the standards of representation for the young people concerned.

In recent years, there has been a lot of focus on the experiences of young people in youth proceedings. Lord Carlile of Berriew CBE QC chaired the Inquiry into the Operation and Effectiveness of the Youth Court, which published its findings in June 2014.

In October 2014 the BSB, along with CILEx Regulation, commissioned a review into the standards of advocacy in youth proceedings. Our review found that advocacy standards in youth proceedings were mixed. While there were examples of good practice, young defendants could not be assured of getting competent representation every time. The package of measures that we announced recently, and which are explained in this article, have been developed directly from the evidence that we obtained from our comprehensive review.

The main focus of our review was the work of barristers and chartered legal executive advocates. The Solicitors Regulation Authority has also developed its own youth court specialist support package for solicitors.

In December 2016, we welcomed the Ministry of Justice’s review by Charlie Taylor into youth justice. It made 36 recommendations to improve the youth justice system including placing a strong emphasis on the importance of high standards of advocacy.

As a public interest regulator, I believe this is exactly the type of area in which we should be focusing our attention. That’s not because we want to be critical of barristers operating in this field—far from it, in fact. But because we think more should be done to support them. One of the ways that we can do this is to call for greater value to be placed on youth proceedings advocacy, both by the profession as a whole and also by the Ministry of Justice.

We think it is wrong that this work is underfunded by the public purse. Increasingly, more and more serious cases are being heard in the youth court—cases that can have devastating long-term effects for the young people involved, especially if their experience of the justice system is negative.

One of the consequences of this underfunding is that it is often seen by the profession as a way for junior barristers to 'cut their teeth'. We think this is wrong as well. We think youth work should be seen as a specialist area of practice. And that practitioners should be supported with appropriate training and encouraged to deliver consistently the unique competences required when representing young people.

Because we believe this is all in the best interests of young people, we recently announced a package of measures to address these issues.

Our approach is to ensure that youth court barristers are equipped with the knowledge, skills and attributes needed to provide competent representation. These are set out in our recently published Youth Proceedings Competences document. It outlines the key competences that barristers who undertake youth proceedings must meet, along with some supporting guidance about how to meet those competences. The competences themselves have been developed collaboratively with organisations across the youth justice sector. They include specialist requirements in the following areas:

Later in the year, we will be introducing compulsory registration for barristers practising in youth advocacy. Registration will allow us to identify all barristers who represent young people and to ensure that they can demonstrate the specialist knowledge, skills and attributes set out in the competences document.

We do not intend to take a heavy handed approach to our regulation in this area. We want to work alongside registered youth practitioners to help them develop these competences over time through training and CPD.

We are aware that there have been arguments to make training for advocates in the youth court compulsory. As we want to regulate proportionately, we do not currently intend to make training compulsory. This is because we are mindful that for now, youth court work tends to be lower paid and we do not want to discourage barristers away from this work. We will gather evidence on the impact our regulation is having and revise our approach if standards are not improving.

We are also working with charity legal service providers, such as Just for Kids Law's Youth Justice Legal Centre, and other legal regulators to ensure that there is competent representation no matter whether the legal representative is a barrister, solicitor-advocate or chartered legal executive. We will also continue to work with the Youth Justice Board, the judiciary and youth offending teams to raise awareness of our competences and their impact on advocacy standards. The engagement of stakeholders from across the sector is invaluable on such an important agenda, so we are particularly pleased to be attending the Youth Justice Summit run by the Youth Justice Legal Centre on 12 May 2017.

Young people's needs may be complex and challenging, but that does not mean they do not have the same rights as anyone else to access to justice.

Contributor Oliver Hanmer, BSB Director of Regulatory Assurance

Case study: advocacy in the youth court

Juwon was 16 years old when he was arrested after being found asleep in a flat that had been broken into. He was charged with burglary and bailed to appear at a youth court. At court he was polite, answered questions when asked, and agreed with the police statements. On this basis he was advised to plead guilty.

The court heard he was in school and hoped to become a plumber. He was apologetic and remorseful. As he was automatically eligible for a referral order the hearing lasted a few minutes.

In the weeks that followed the Youth Offending Team (YOT) discovered Juwon was homeless. He had been living with his uncle and aunt; shortly before the burglary allegation, Juwon's uncle had died unexpectedly. Juwon was very close to his uncle and struggled to come to terms with his death. On the night of his arrest, Juwon had been drinking heavily and has no memory of how he came to be in the flat. His aunt was understandably upset at Juwon's behaviour and lack of respect, so cut all ties with him; leaving his belongings in black bags outside her home and refusing to come to the police station or court.

Juwon did not volunteer any of this. A barrister with youth justice expertise would have known the importance of finding out background information and it is highly likely the Crown Prosecution Service would have reviewed its decision to prosecute. Regrettably, Juwon now has a criminal record for an offence of domestic burglary. This is likely to prove a barrier to his career aspirations.

Oliver Hanmer outlines the regulator’s new measures to improve standards in youth court advocacy

No one could argue against the notion that every child deserves the very best chance in life.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar