*/

Women are still leaving the Bar. So what are we doing about it? Professor Jo Delahunty QC takes a memory trip through recent times to assess whether times are changing, or it’s still a case of sticky floor and glass ceiling...

In 2017 I delivered a lecture on the position of women in our profession, looking at our ability to attract, retain and elevate female entrants as their skills warranted. I fully anticipated I would be celebrating the achievements of women at the Bar. I was misguided. I concluded that able women had been failed by their profession – leaking talent from an entry base line of equality to a silk pool drained of female talent:

When I and others took a public platform to decry that state of affairs, it felt, for the first time, that we had found an audience prepared to listen to what had been talked about in professional circles for years. Public and press interest in discrimination had been fuelled by the ‘Me too’ movement. The time, I believed, was ripe for positive change.

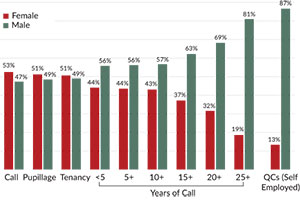

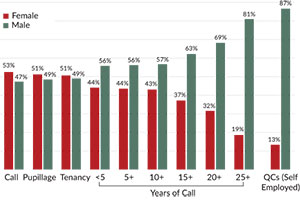

So, what have we achieved three years on? Look to the BSB’s latest available statistics (Diversity at the Bar 2019, published in January 2020). The ratio of women to men at pupillage is still ascendant at 54.8% to 45.2%, yet women constitute 38.0% of the Bar overall compared to an estimate of 50.2% of the UK working age population. The proportion of women at the Bar has increased 0.6 percentage points since the snapshot taken in December 2018. The proportion of female QCs has increased from 13% in 2016 to 16.2% in 2019. As the Bar Council has starkly warned: at this rate women will never take silk in equal numbers to men.

Think back to Helena Kennedy QC’s words in Eve was framed: Women and British Justice. In the revised edition (2005), Kennedy concluded that the issues that stifle diversity at the Bar are to be found in the apocalyptic horsemen wearing the colours of ‘practice bias’, ‘status’, ‘income’ and ‘parenthood’:

The 2019 Association of Women Barristers report, In the Age of ‘Us Too?’ Moving towards a zero-tolerance attitude to harassment and bullying at the Bar suggested the following issues:

In 2019, Chris Henley QC as Chair of the Criminal Bar Association brought to our attention several incidents in which male judges made disparaging comments to women barristers in court. He concluded: ‘Talented women are leaving criminal practice... Even the most successful junior women increasingly have had enough. They can get easier, better paid jobs elsewhere, where they will be supported, be treated with respect and where the conditions are flexible and compatible with family life. Most men want this too. It is patently not being taken sufficiently seriously.’

The adverse effect of working practices and pay on women’s wellbeing at the Bar is a key contributor to such disparity in retention rates. Caring responsibilities are disproportionately high compared to male colleagues. At the independent Bar there is little flexibility with late service of evidence and skeleton arguments requiring urgent responses, often after hours and following long days in court leaving little time for family life. Whether we practise in family law or criminal law, immigration or housing – cuts to legal aid have resulted in a loss of income to all. Days off court are not remunerated, meaning time off for caring responsibilities results in further loss of income. Retention at the Bar becomes an issue when compared to the perks of being in employed practice with more regular and flexible working hours, holiday and sick pay plus pension.

But the attrition factors that lead to loss of senior women does not explain why those who do stay the course and take silk have less visibility at the higher levels of practice than men. That has, I suggest, to be down to institutionalised industry bias.

Lady Hale in the opening keynote address at the 2019 Bar Conference highlighted how the number of women appearing in the Supreme Court in 2009-2010 made up 21% of appearances before the court. That hasn’t changed in the last few years with 23% of appearances being women in 2019, and the figure even falling during this time to 20% in 2014-2015.

Mikolaj Barczentewicz, a public law lecturer at the University of Surrey, designed an algorithm that analysed all the cases heard in the Supreme Court (SC) and generated a database of all barristers who had appeared before it (Litigation in the UK Supreme Court: collecting and exploring the data). He shared his report with the public in December 2019, making plain it was a work in progress, and offered a valuable insight into the visibility of women in the highest court of our land: only 8 of the 48 barristers who had most frequently addressed Britain’s highest court since its inception 11 years ago were women. Only two of the top 10 were women. Out of the 509 female advocates who appeared before the SC: 417 had their first case in the SC without silk (including 29 silks) and 92 had had their first SC case as silk.

This underscores the importance of being in the SC as a career enhancer. But while women might be being seen in the SC, they aren’t being heard, because the speaking parts (taken by the silks appearing on the front row) are overwhelmingly male. Women are the juniors: not the leaders.

Karon Monaghan QC said in an article published in The Times on 24 October 2019: ‘The near absence of women silks will be no surprise to anyone who appears in the Supreme Court.’ Karon said that solicitors and clients too often chose men to represent them because they thought they would have more gravitas. ‘Men therefore appear in greater numbers,’ she said. ‘Those men then get a reputation for being good in the Supreme Court, as having the ear of the court and as silks who can be relied upon to perform well, so continuing the cycle.’

This is no sour grapes: Karon is one of the women who is most regularly instructed to appear at the highest court in our land. When women like Karon say that ‘the persistent under representation of women is likely to do with straightforward prejudice and stereotyping, and it is self-perpetuating’, she is telling it like it is.

These are some of my suggestions to address lack of female advancement in practice. They aren’t radical:

Take every opportunity to advance your skill set. Be hungry to improve. How else will you have the framework to build upon for more senior roles? For example, the Keble Advanced Advocacy Course is an incredible advancement programme. It is said to be ‘the most demanding and intensive of any advocacy course in the UK’. The course is massively subsidised. Each Inn offers five scholarships and the Criminal Bar Association also offers five.

Mentors bridge the gap between stages of a career that are otherwise a cavernous void to the junior member. They pass on advice and contacts but their real value, I believe, is in making senior roles more accessible and relatable to the young. If they are relatable, they can be emulated: it makes aspiration more real and career dreams more ambitious. Mentoring schemes to increase diversity and inclusion by supporting aspiring female barristers include those run by the Association for Women Barristers, Women in Criminal Law, Women in Family Law and Western Circuit Women’s Forum (WCWF, see more below) to name just a few.

And mentoring isn’t just for the beleaguered public law legal aid sector. We need more women in commercial work. I have been deeply encouraged by the initiative set up by some commercial sets to reach out to applicants. One Essex Court, Brick Court, Essex Court and Fountain Court chambers collaborated to create a series of events at a number of universities directed at gender diversity called ‘A career as a commercial barrister: a great choice for women’.

The WCWF, under the headship of the phenomenal Kate Brunner QC, leads the way in many areas including a mentoring scheme for young women barristers, social networking and training events, research projects and lobbying on issues that affect women barristers.

Being a mentor is, I believe, a moral and professional obligation if we really mean to make changes at the Bar.

Among findings from the Law Society’s Women in Leadership in Law round tables – and just as relevant to the Bar – is that it is crucial for leaders to be aware of their bias to prevent it from influencing business decisions and colleagues alike. This can help underpin a culture of awareness that is the foundation for change. Supporting women in the workplace is a key imperative to prevent bias.

Men should not be excluded from this role. As Lady Hale said at the Bar Conference last year, ‘Not all women are feminists but many men are and women would never have got anywhere unless some men had realised that if the law treated them in the way it treated women they wouldn’t tolerate it.’

The Law Society’s Male Champions for Change: Toolkit offers insight and guidance on what individuals can do to accelerate the rate of progress within the legal profession as a whole. It warrants adoption by our profession.

In addition to better supporting women at the Bar we need to make sure that we make the Bar a visible and accessible profession to the young women who have the potential to join us – the Bar needs to look out for the next generation of change makers. I am an Ambassador of the recently launched charity Bridging the Bar (BTB, bridgingthebar.org) set up by the remarkable Mass Ndow-Njie. BTB is committed to the promotion of equal opportunities and diversity at the Bar at all levels. Join it. Make a difference. Every voice, every action counts towards making the Bar less white, less straight, less middle class and less male.

The International Bar Association in Us too? Bullying and Sexual Harassment in the Legal Profession (May 2019) reported the largest ever survey on bullying and sexual harassment in legal profession, with 6,980 respondents from 135 countries. The statistics indicated bullying was rife (one in two female respondents and one in three male respondents) and sexual harassment common. The IBA ‘called time’ on ‘endemic’ bullying and sexual harassment in the legal profession. The cries of outrage and demands for change traversed nations.

The times are a changing: the Bar Council has partnered with Spot.com to support members of profession who are victims of, or witnesses to, discrimination, harassment or bullying – either by other members of profession, solicitors, judges or others. This is a real step forward and I commend the Bar Council, the Specialist Associations and the Inns for their drive and determination to make it happen.

The WCWF took the lead by going beyond restating what the factors are that lead to the loss of women at 10-15 years plus. They published Back to the Bar: Best Practice Guide Retention and Progression after Parental Leave (October 2019). It is, quite simply, a superb piece of work. The vital role that clerks have to play is highlighted. The importance of parent friendly chambers culture is identified. The value of maintaining links and ‘reach out’ contact from chambers is made explicit. It should be read by every head of chambers, senior clerk and chambers management team in my view. And the default position should be to adopt it.

The discriminatory impact of extended court hours on men and women with caring responsibilities was being shouted out by the family and criminal Bar before COVID struck. Whether remote hearings, introduced as a necessity in family cases, will remain once the court system is able to function in person is a dynamic question. A hybrid remote/in person practice opens up possibilities for more caring-compatible work practices that could transform a working parents ability to sustain and develop a career otherwise by hampered by lack of flexible childcare. Watch this space.

Diversity, of course, is not just about gender. The guiding principles of our laws are justice, fairness and equality. If we believe in them at the Bar and Judiciary, we should agitate and act to achieve change to ensure that fairness and equality are visibly embodied in our ranks:

In 2017 I delivered a lecture on the position of women in our profession, looking at our ability to attract, retain and elevate female entrants as their skills warranted. I fully anticipated I would be celebrating the achievements of women at the Bar. I was misguided. I concluded that able women had been failed by their profession – leaking talent from an entry base line of equality to a silk pool drained of female talent:

When I and others took a public platform to decry that state of affairs, it felt, for the first time, that we had found an audience prepared to listen to what had been talked about in professional circles for years. Public and press interest in discrimination had been fuelled by the ‘Me too’ movement. The time, I believed, was ripe for positive change.

So, what have we achieved three years on? Look to the BSB’s latest available statistics (Diversity at the Bar 2019, published in January 2020). The ratio of women to men at pupillage is still ascendant at 54.8% to 45.2%, yet women constitute 38.0% of the Bar overall compared to an estimate of 50.2% of the UK working age population. The proportion of women at the Bar has increased 0.6 percentage points since the snapshot taken in December 2018. The proportion of female QCs has increased from 13% in 2016 to 16.2% in 2019. As the Bar Council has starkly warned: at this rate women will never take silk in equal numbers to men.

Think back to Helena Kennedy QC’s words in Eve was framed: Women and British Justice. In the revised edition (2005), Kennedy concluded that the issues that stifle diversity at the Bar are to be found in the apocalyptic horsemen wearing the colours of ‘practice bias’, ‘status’, ‘income’ and ‘parenthood’:

The 2019 Association of Women Barristers report, In the Age of ‘Us Too?’ Moving towards a zero-tolerance attitude to harassment and bullying at the Bar suggested the following issues:

In 2019, Chris Henley QC as Chair of the Criminal Bar Association brought to our attention several incidents in which male judges made disparaging comments to women barristers in court. He concluded: ‘Talented women are leaving criminal practice... Even the most successful junior women increasingly have had enough. They can get easier, better paid jobs elsewhere, where they will be supported, be treated with respect and where the conditions are flexible and compatible with family life. Most men want this too. It is patently not being taken sufficiently seriously.’

The adverse effect of working practices and pay on women’s wellbeing at the Bar is a key contributor to such disparity in retention rates. Caring responsibilities are disproportionately high compared to male colleagues. At the independent Bar there is little flexibility with late service of evidence and skeleton arguments requiring urgent responses, often after hours and following long days in court leaving little time for family life. Whether we practise in family law or criminal law, immigration or housing – cuts to legal aid have resulted in a loss of income to all. Days off court are not remunerated, meaning time off for caring responsibilities results in further loss of income. Retention at the Bar becomes an issue when compared to the perks of being in employed practice with more regular and flexible working hours, holiday and sick pay plus pension.

But the attrition factors that lead to loss of senior women does not explain why those who do stay the course and take silk have less visibility at the higher levels of practice than men. That has, I suggest, to be down to institutionalised industry bias.

Lady Hale in the opening keynote address at the 2019 Bar Conference highlighted how the number of women appearing in the Supreme Court in 2009-2010 made up 21% of appearances before the court. That hasn’t changed in the last few years with 23% of appearances being women in 2019, and the figure even falling during this time to 20% in 2014-2015.

Mikolaj Barczentewicz, a public law lecturer at the University of Surrey, designed an algorithm that analysed all the cases heard in the Supreme Court (SC) and generated a database of all barristers who had appeared before it (Litigation in the UK Supreme Court: collecting and exploring the data). He shared his report with the public in December 2019, making plain it was a work in progress, and offered a valuable insight into the visibility of women in the highest court of our land: only 8 of the 48 barristers who had most frequently addressed Britain’s highest court since its inception 11 years ago were women. Only two of the top 10 were women. Out of the 509 female advocates who appeared before the SC: 417 had their first case in the SC without silk (including 29 silks) and 92 had had their first SC case as silk.

This underscores the importance of being in the SC as a career enhancer. But while women might be being seen in the SC, they aren’t being heard, because the speaking parts (taken by the silks appearing on the front row) are overwhelmingly male. Women are the juniors: not the leaders.

Karon Monaghan QC said in an article published in The Times on 24 October 2019: ‘The near absence of women silks will be no surprise to anyone who appears in the Supreme Court.’ Karon said that solicitors and clients too often chose men to represent them because they thought they would have more gravitas. ‘Men therefore appear in greater numbers,’ she said. ‘Those men then get a reputation for being good in the Supreme Court, as having the ear of the court and as silks who can be relied upon to perform well, so continuing the cycle.’

This is no sour grapes: Karon is one of the women who is most regularly instructed to appear at the highest court in our land. When women like Karon say that ‘the persistent under representation of women is likely to do with straightforward prejudice and stereotyping, and it is self-perpetuating’, she is telling it like it is.

These are some of my suggestions to address lack of female advancement in practice. They aren’t radical:

Take every opportunity to advance your skill set. Be hungry to improve. How else will you have the framework to build upon for more senior roles? For example, the Keble Advanced Advocacy Course is an incredible advancement programme. It is said to be ‘the most demanding and intensive of any advocacy course in the UK’. The course is massively subsidised. Each Inn offers five scholarships and the Criminal Bar Association also offers five.

Mentors bridge the gap between stages of a career that are otherwise a cavernous void to the junior member. They pass on advice and contacts but their real value, I believe, is in making senior roles more accessible and relatable to the young. If they are relatable, they can be emulated: it makes aspiration more real and career dreams more ambitious. Mentoring schemes to increase diversity and inclusion by supporting aspiring female barristers include those run by the Association for Women Barristers, Women in Criminal Law, Women in Family Law and Western Circuit Women’s Forum (WCWF, see more below) to name just a few.

And mentoring isn’t just for the beleaguered public law legal aid sector. We need more women in commercial work. I have been deeply encouraged by the initiative set up by some commercial sets to reach out to applicants. One Essex Court, Brick Court, Essex Court and Fountain Court chambers collaborated to create a series of events at a number of universities directed at gender diversity called ‘A career as a commercial barrister: a great choice for women’.

The WCWF, under the headship of the phenomenal Kate Brunner QC, leads the way in many areas including a mentoring scheme for young women barristers, social networking and training events, research projects and lobbying on issues that affect women barristers.

Being a mentor is, I believe, a moral and professional obligation if we really mean to make changes at the Bar.

Among findings from the Law Society’s Women in Leadership in Law round tables – and just as relevant to the Bar – is that it is crucial for leaders to be aware of their bias to prevent it from influencing business decisions and colleagues alike. This can help underpin a culture of awareness that is the foundation for change. Supporting women in the workplace is a key imperative to prevent bias.

Men should not be excluded from this role. As Lady Hale said at the Bar Conference last year, ‘Not all women are feminists but many men are and women would never have got anywhere unless some men had realised that if the law treated them in the way it treated women they wouldn’t tolerate it.’

The Law Society’s Male Champions for Change: Toolkit offers insight and guidance on what individuals can do to accelerate the rate of progress within the legal profession as a whole. It warrants adoption by our profession.

In addition to better supporting women at the Bar we need to make sure that we make the Bar a visible and accessible profession to the young women who have the potential to join us – the Bar needs to look out for the next generation of change makers. I am an Ambassador of the recently launched charity Bridging the Bar (BTB, bridgingthebar.org) set up by the remarkable Mass Ndow-Njie. BTB is committed to the promotion of equal opportunities and diversity at the Bar at all levels. Join it. Make a difference. Every voice, every action counts towards making the Bar less white, less straight, less middle class and less male.

The International Bar Association in Us too? Bullying and Sexual Harassment in the Legal Profession (May 2019) reported the largest ever survey on bullying and sexual harassment in legal profession, with 6,980 respondents from 135 countries. The statistics indicated bullying was rife (one in two female respondents and one in three male respondents) and sexual harassment common. The IBA ‘called time’ on ‘endemic’ bullying and sexual harassment in the legal profession. The cries of outrage and demands for change traversed nations.

The times are a changing: the Bar Council has partnered with Spot.com to support members of profession who are victims of, or witnesses to, discrimination, harassment or bullying – either by other members of profession, solicitors, judges or others. This is a real step forward and I commend the Bar Council, the Specialist Associations and the Inns for their drive and determination to make it happen.

The WCWF took the lead by going beyond restating what the factors are that lead to the loss of women at 10-15 years plus. They published Back to the Bar: Best Practice Guide Retention and Progression after Parental Leave (October 2019). It is, quite simply, a superb piece of work. The vital role that clerks have to play is highlighted. The importance of parent friendly chambers culture is identified. The value of maintaining links and ‘reach out’ contact from chambers is made explicit. It should be read by every head of chambers, senior clerk and chambers management team in my view. And the default position should be to adopt it.

The discriminatory impact of extended court hours on men and women with caring responsibilities was being shouted out by the family and criminal Bar before COVID struck. Whether remote hearings, introduced as a necessity in family cases, will remain once the court system is able to function in person is a dynamic question. A hybrid remote/in person practice opens up possibilities for more caring-compatible work practices that could transform a working parents ability to sustain and develop a career otherwise by hampered by lack of flexible childcare. Watch this space.

Diversity, of course, is not just about gender. The guiding principles of our laws are justice, fairness and equality. If we believe in them at the Bar and Judiciary, we should agitate and act to achieve change to ensure that fairness and equality are visibly embodied in our ranks:

Women are still leaving the Bar. So what are we doing about it? Professor Jo Delahunty QC takes a memory trip through recent times to assess whether times are changing, or it’s still a case of sticky floor and glass ceiling...

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar