*/

Adrian Jack follows up on the recruitment crisis in the High Court and reports on recent developments

The High Court recruitment crisis was highlighted in the July issue of Counsel .

Since then the summer budget has drastically worsened the position by slashing the annual allowance for pension contributions and continuing the one per cent cap on salary increases. Moreover, the problem of recruitment now extends to the circuit bench.

Judicial salaries generally have been hit by the pay freeze introduced after the global economic crisis, followed from 2011 by one per cent annual pay increases and the introduction of substantial pension contributions. This affected all judges. However, it was a technical change whereby the New Judicial Pension Scheme (NJPS), which took effect on 1 April 2015, became a “registered” scheme, which made a dramatic difference in the take home pay of younger High Court judges as against older High Court judges.

A 59-year-old remains in the older Judicial Pension Scheme (JPS) under the transitional arrangements, whereas a 48-year-old will be in the NJPS. A judge in the NJPS is subject to the “annual allowance” on pension contributions. In the current tax year this is £40,000. Contributions above that are taxed at 45 per cent.

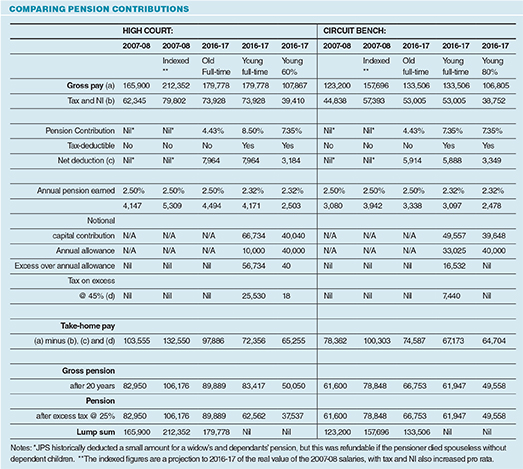

In registered final salary pension schemes (such as the NJPS), the “contribution” is a notional capital payment of 16 times the pension earned. The notional contribution for the 48-year-old is £66,073, which is above the £40,000, so the 48-year-old pays £11,733 additional tax. His or her take home pay is thus currently nearly £12,000 less than the net salary of the 59-year-old. (The full details are in the earlier article.)

The changes in the summer Budget increase this differential. Those earning over £150,000 have their annual allowance reduced by one pound for every two over the limit until the annual allowance reaches £10,000. Moreover the £150,000 figure includes the pension contribution.

Next year’s salary rise is limited to one per cent, so High Court judges will be on £179,778. The notional capital contribution to the 48-year-old’s pension will be £66,734. This is £56,734 above the £10,000 annual allowance. The additional tax will therefore be £25,530. A 59-year-old in the JPS will not pay this tax, thus increasing the difference between younger and older judges in take home pay to over £25,000. The 48-year-old’s take home pay is 73.9 per cent of the 59-year-old’s — leading to a potential age discrimination (and probably sex and race discrimination) claim.

If a High Court judge’s net salary in 2007–08 had increased in line with RPI, the projected take home in 2016–17 would have been £132,550. Instead a 59-year-old will take home £97,883 (73.8 per cent of £132,550) and a 48-year-old £72,356 (a mere 54.8 per cent in real terms, and less than an older Circuit Judge on £74,587).

Moreover the change will affect circuit judges as well as High Court judges. The maths is more complicated. If we assume a one per cent pay rise, the circuit judge will be on £133,506. The notional capital contribution to the NJPS will be £49,557. Adding £133,506 to £49,557 gives £183,063. This is £33,063 over the £150,000 threshold at which the annual allowance is clawed back. Half of £33,063 is £16,531. A younger circuit judge’s annual allowance is thus £33,025, calculated as £16,494 (£150,000 minus £133,506) plus £16,531. The excess capital contribution is £16,532 (£49,557 minus £33,025). The tax at 45 per cent on £16,532 will be £7,440, which will be the difference in net earnings of a younger against an older circuit judge.

In my previous article in Counsel (July 2015), the attractions of part-time working were highlighted. These are even greater following the budget. As can be seen from the table, a younger High Court judge working 60 per cent will have a take home pay of £65,255, whereas a younger full-timer, working 67 per cent more days, will receive only 10.8 per cent more net wages at £72,356. (An older full-timer will be on 50 per cent more at £97,886.)

Likewise a circuit judge working 80 per cent will receive £64,704 take home, whilst the young full-timer will be on just 3.8 per cent more at £67,173.

This is surely unsustainable.

Contributor Adrian Jack

Since then the summer budget has drastically worsened the position by slashing the annual allowance for pension contributions and continuing the one per cent cap on salary increases. Moreover, the problem of recruitment now extends to the circuit bench.

Judicial salaries generally have been hit by the pay freeze introduced after the global economic crisis, followed from 2011 by one per cent annual pay increases and the introduction of substantial pension contributions. This affected all judges. However, it was a technical change whereby the New Judicial Pension Scheme (NJPS), which took effect on 1 April 2015, became a “registered” scheme, which made a dramatic difference in the take home pay of younger High Court judges as against older High Court judges.

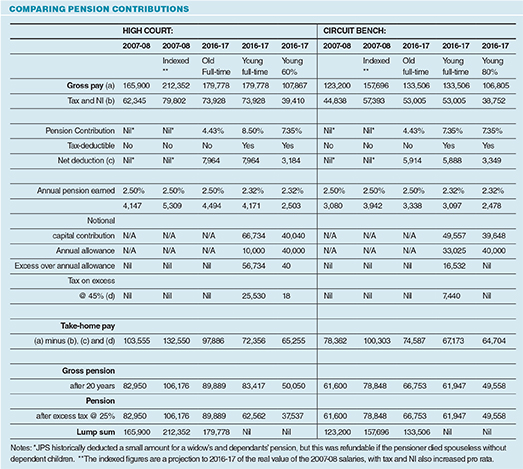

A 59-year-old remains in the older Judicial Pension Scheme (JPS) under the transitional arrangements, whereas a 48-year-old will be in the NJPS. A judge in the NJPS is subject to the “annual allowance” on pension contributions. In the current tax year this is £40,000. Contributions above that are taxed at 45 per cent.

In registered final salary pension schemes (such as the NJPS), the “contribution” is a notional capital payment of 16 times the pension earned. The notional contribution for the 48-year-old is £66,073, which is above the £40,000, so the 48-year-old pays £11,733 additional tax. His or her take home pay is thus currently nearly £12,000 less than the net salary of the 59-year-old. (The full details are in the earlier article.)

The changes in the summer Budget increase this differential. Those earning over £150,000 have their annual allowance reduced by one pound for every two over the limit until the annual allowance reaches £10,000. Moreover the £150,000 figure includes the pension contribution.

Next year’s salary rise is limited to one per cent, so High Court judges will be on £179,778. The notional capital contribution to the 48-year-old’s pension will be £66,734. This is £56,734 above the £10,000 annual allowance. The additional tax will therefore be £25,530. A 59-year-old in the JPS will not pay this tax, thus increasing the difference between younger and older judges in take home pay to over £25,000. The 48-year-old’s take home pay is 73.9 per cent of the 59-year-old’s — leading to a potential age discrimination (and probably sex and race discrimination) claim.

If a High Court judge’s net salary in 2007–08 had increased in line with RPI, the projected take home in 2016–17 would have been £132,550. Instead a 59-year-old will take home £97,883 (73.8 per cent of £132,550) and a 48-year-old £72,356 (a mere 54.8 per cent in real terms, and less than an older Circuit Judge on £74,587).

Moreover the change will affect circuit judges as well as High Court judges. The maths is more complicated. If we assume a one per cent pay rise, the circuit judge will be on £133,506. The notional capital contribution to the NJPS will be £49,557. Adding £133,506 to £49,557 gives £183,063. This is £33,063 over the £150,000 threshold at which the annual allowance is clawed back. Half of £33,063 is £16,531. A younger circuit judge’s annual allowance is thus £33,025, calculated as £16,494 (£150,000 minus £133,506) plus £16,531. The excess capital contribution is £16,532 (£49,557 minus £33,025). The tax at 45 per cent on £16,532 will be £7,440, which will be the difference in net earnings of a younger against an older circuit judge.

In my previous article in Counsel (July 2015), the attractions of part-time working were highlighted. These are even greater following the budget. As can be seen from the table, a younger High Court judge working 60 per cent will have a take home pay of £65,255, whereas a younger full-timer, working 67 per cent more days, will receive only 10.8 per cent more net wages at £72,356. (An older full-timer will be on 50 per cent more at £97,886.)

Likewise a circuit judge working 80 per cent will receive £64,704 take home, whilst the young full-timer will be on just 3.8 per cent more at £67,173.

This is surely unsustainable.

Contributor Adrian Jack

Adrian Jack follows up on the recruitment crisis in the High Court and reports on recent developments

The High Court recruitment crisis was highlighted in the July issue of Counsel.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar