*/

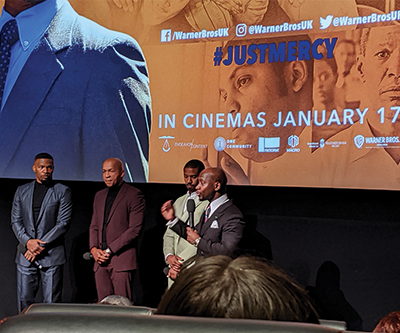

Starring Michael B Jordan as American civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson, and Jamie Foxx as Walter McMillian, a man who was wrongly convicted and sentenced to death, Just Mercy is a film adaptation of one Stevenson’s most important real-life cases, and takes its title from his 2014 book of the same name. As a fact-based retelling of a grave miscarriage of justice, the film is extremely interesting; indeed, Stevenson’s book (and audiobook) has already proved to be a very popular source of inspiration among many young and aspiring lawyers.

The film recounts Stevenson’s life story, from a graduate of Harvard Law School, to founder of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI): a not-for-profit that provides legal representation to prisoners who may have been wrongly convicted of crimes, poor prisoners without effective representation, and others who may have been denied a fair trial.

As a young lawyer, Stevenson resolves to overturn the murder conviction of McMillian, an African-American man who was accused of killing a young white woman who worked as a clerk in a dry cleaning store in Monroeville, Alabama in 1986, and who spent six years on death row.

The scene where Stevenson pays a visit to McMillian’s family home in the Deep South and establishes there was a complete alibi, is excellent, and by his sheer tenacity, Stevenson was able to prove the conviction was obtained by Police coercion, and wholly unreliable evidence.

The film also tracks other clients mentioned in Stevenson’s book, including the troubling state execution of Herbert Richardson, whose mental health problems resulting from service in the Vietnam War were ignored at his capital trial, giving much pause for thought on the justness of the death penalty as a form of punishment.

In my view, the film deserves a great deal of admiration, for its attempt to bring attention to the systematic flaws, and blatant racism, inherent in the US criminal justice system. Moreover, the film is also remarkable for the manner in which intermingles footage from earlier documentaries, for the astonishing likeness created of the actual people it concerns, and for its depiction of 1980s criminal litigation. There is also an insight into the motivations behind Stevenson’s work and his distinguished legal career: as a victim of racism himself, and as a person of Christian faith, with great force he reminds us that: ‘We all need mercy, we all need justice, and perhaps, we all need some measure of unmerited grace.’

The closing credits make clear that the film is based on factual events. The work of the EJI continues, as the high levels of incarceration in the US mean that there is much advocacy to be done for those facing racial bias and discrimination in their criminal justice system.

Our justice system too, disproportionately charges and tries those that are from Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority communities (The Lammy Review, 2017). Whilst the subject matter is heavy and the film can evoke many emotions (and the US style of advocacy and courtroom closing speeches would be unrealistic to perform in England and Wales) it could nevertheless do much to motivate lawyers in this jurisdiction, in defending the rights of the poor and disadvantaged.

Starring Michael B Jordan as American civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson, and Jamie Foxx as Walter McMillian, a man who was wrongly convicted and sentenced to death, Just Mercy is a film adaptation of one Stevenson’s most important real-life cases, and takes its title from his 2014 book of the same name. As a fact-based retelling of a grave miscarriage of justice, the film is extremely interesting; indeed, Stevenson’s book (and audiobook) has already proved to be a very popular source of inspiration among many young and aspiring lawyers.

The film recounts Stevenson’s life story, from a graduate of Harvard Law School, to founder of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI): a not-for-profit that provides legal representation to prisoners who may have been wrongly convicted of crimes, poor prisoners without effective representation, and others who may have been denied a fair trial.

As a young lawyer, Stevenson resolves to overturn the murder conviction of McMillian, an African-American man who was accused of killing a young white woman who worked as a clerk in a dry cleaning store in Monroeville, Alabama in 1986, and who spent six years on death row.

The scene where Stevenson pays a visit to McMillian’s family home in the Deep South and establishes there was a complete alibi, is excellent, and by his sheer tenacity, Stevenson was able to prove the conviction was obtained by Police coercion, and wholly unreliable evidence.

The film also tracks other clients mentioned in Stevenson’s book, including the troubling state execution of Herbert Richardson, whose mental health problems resulting from service in the Vietnam War were ignored at his capital trial, giving much pause for thought on the justness of the death penalty as a form of punishment.

In my view, the film deserves a great deal of admiration, for its attempt to bring attention to the systematic flaws, and blatant racism, inherent in the US criminal justice system. Moreover, the film is also remarkable for the manner in which intermingles footage from earlier documentaries, for the astonishing likeness created of the actual people it concerns, and for its depiction of 1980s criminal litigation. There is also an insight into the motivations behind Stevenson’s work and his distinguished legal career: as a victim of racism himself, and as a person of Christian faith, with great force he reminds us that: ‘We all need mercy, we all need justice, and perhaps, we all need some measure of unmerited grace.’

The closing credits make clear that the film is based on factual events. The work of the EJI continues, as the high levels of incarceration in the US mean that there is much advocacy to be done for those facing racial bias and discrimination in their criminal justice system.

Our justice system too, disproportionately charges and tries those that are from Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority communities (The Lammy Review, 2017). Whilst the subject matter is heavy and the film can evoke many emotions (and the US style of advocacy and courtroom closing speeches would be unrealistic to perform in England and Wales) it could nevertheless do much to motivate lawyers in this jurisdiction, in defending the rights of the poor and disadvantaged.

Kirsty Brimelow KC, Chair of the Bar, sets our course for 2026

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Asks Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

AlphaBiolabs has donated £500 to The Christie Charity through its Giving Back initiative, helping to support cancer care, treatment and research across Greater Manchester, Cheshire and further afield

Q and A with criminal barrister Nick Murphy, who moved to New Park Court Chambers on the North Eastern Circuit in search of a better work-life balance

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar

Jury-less trial proposals threaten fairness, legitimacy and democracy without ending the backlog, writes Professor Cheryl Thomas KC (Hon), the UK’s leading expert on juries, judges and courts