*/

Structural change brought decline in the quality of legal aid at the same time as the cost tripled – it’s time to return the administration to lawyers, argues Anthony Speaight QC

In the first decade of the 21st century, legal aid was run by a body called the Legal Services Commission (LSC). The LSC had the technical status of a non-departmental public body, which meant that, in contrast to the present Legal Aid Agency, appointments to its board were subject to the principles on public appointments, including advertisement. In 2005 the LSC advertised vacancies for lawyers. Hardly anybody seems to have paid any attention to the advertisement because, a few months later, they advertised again. The then Chair of the Bar, not wanting to miss an opportunity, drew my attention to this and urged me to apply. I duly did so; and set about preparing for the interview.

In the end the LSC found a better suited barrister who had a legal aid practice, which by then I no longer had. But I had a lively hour’s conversation with Sir Michael Barber, the LSC’s then Chairman and a veteran of public bodies, and a couple of officials.

I came away from what proved an interesting episode with two abiding impressions. One was that Whitehall regarded legal aid as if it were a dangerous wild animal they were trying to control. The second was that their attitude was entirely understandable.

What I discovered in my research to prepare for the interview was that legal aid spending resembled a runaway train: I do not believe there is any field of public expenditure which rose as fast as legal aid in the later years of the 20th century. Neither then, nor later, were the facts of how much it had spiraled ever acknowledged by the Bar or the Law Society. So, conversation between the legal profession and government was a dialogue of the deaf.

When retribution ultimately came it turned savage. What started as freezes turned into cuts – not just cuts in money terms, but cuts in real terms (ie after adjustment for inflation). Administration by costs judges, members of the legal profession and experienced Crown Court officials staff turned into administration by bureaucrats who know nothing about the law.

As the years have passed, information on legal aid spending in the 1970s and 1980s has become harder to access. For this reason, as well as lack of interest in the legal professions in statistics which might be helpful to the government, the facts about the actual rise in legal aid spending are not detailed in any publication or paper which I have seen for many years. Not, that is, until March this year.

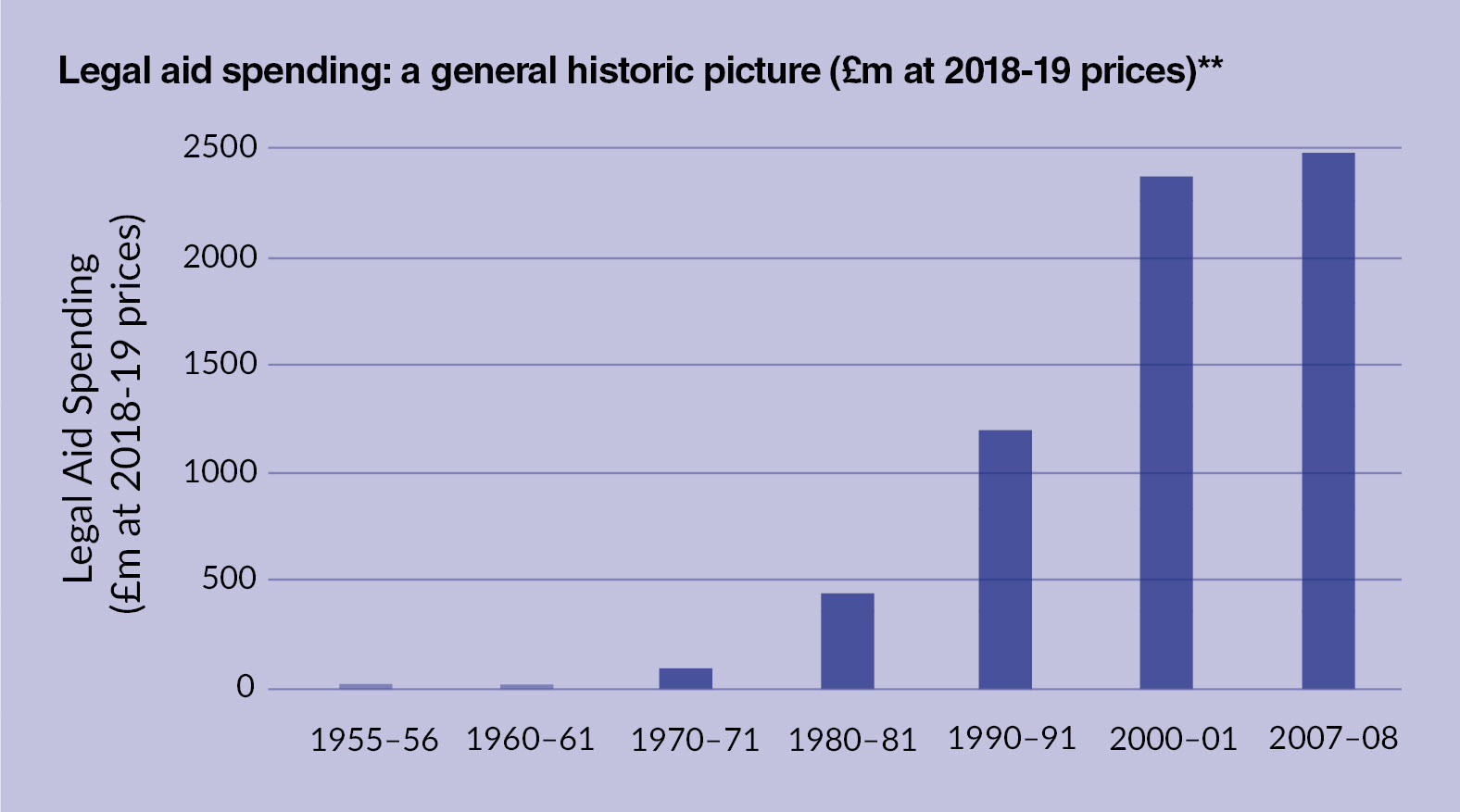

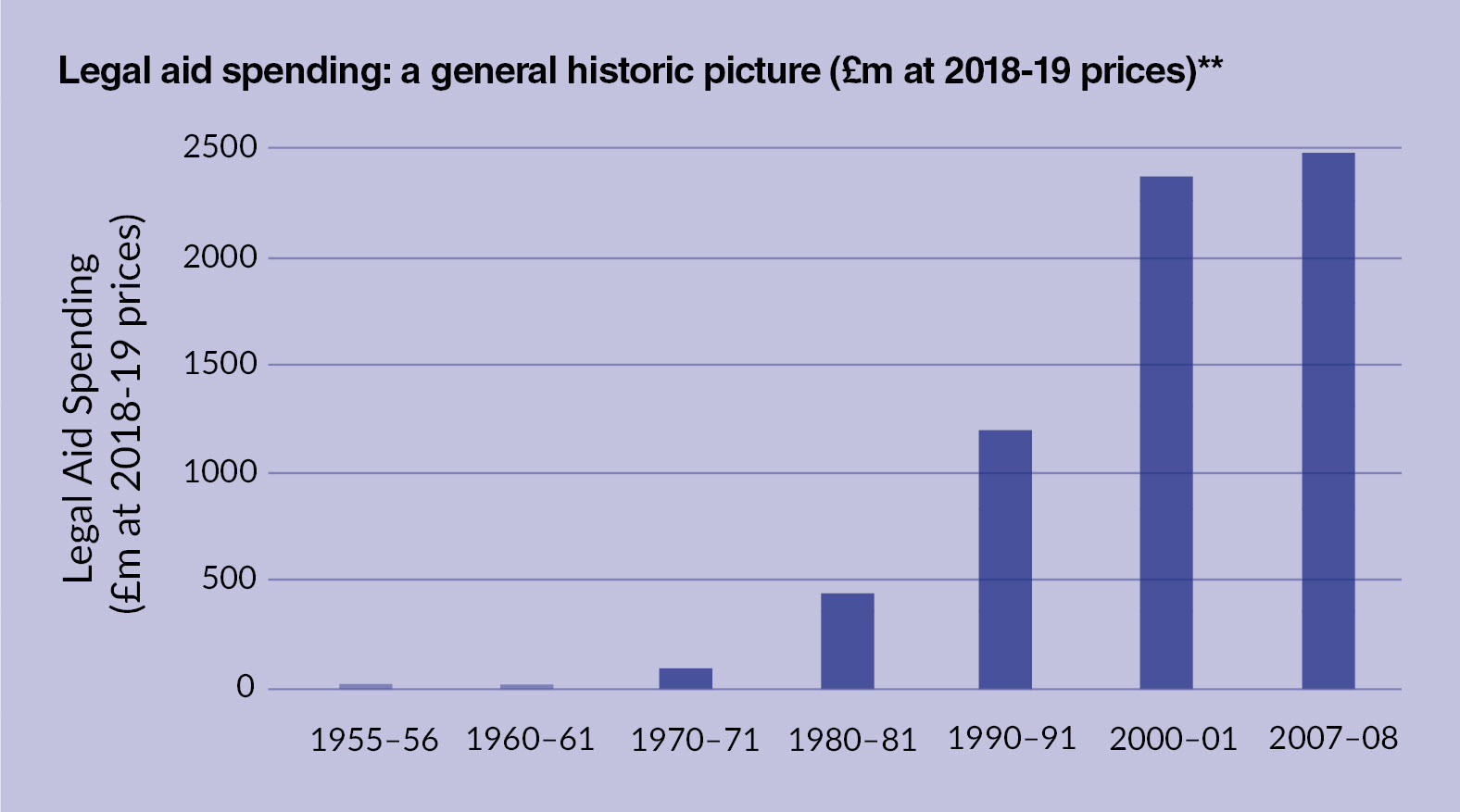

Now the think tank Politeia has used data from official sources in a publication, Reforming Legal Aid (by Sheila Lawlor, Gavin Rice, Jonathan Fisher QC, Max Hardy, Edite Ligere and James Taghdissia). In an account of 20th century policy, it discusses how the figures changed over the years. It also explains that a different basis was used for data collection in the later decades of the last century and the caveats about this change must be respected in making comparisons. Nonetheless the comparison is so stark that errors at the margin would make no difference of significance to the picture. Transferring raw figures into figures adjusted for inflation so that they can be compared on a broadly like-for-like basis, they show the rise at 2018-19 prices presented on the chart below.

The figures for the years for 1970-1 and earlier years are of limited relevance. It was only during the 1970s that legal aid in the newly established Crown Court was moved from the Home Office, that the Green Form scheme began, that the number of divorces grew, and that legal aid was extended to education, welfare and housing cases.

The two figures which are of most interest are:

So, in those two years the scope was broadly comparable* and yet the cost quadrupled.

That quadrupling might be understandable if the quality of legal aid had in some way improved over that period. But the opposite was the case. Whereas in 1979 nearly 80% of the population were in means test terms within the scope of legal aid, by reason of eligibility changes in 1994 this fell to 50%, and went on falling. And whereas in the late 1970s the rates of legal aid payments for criminal and civil work were found by the Bar to be reasonable, in 1987 the Campaign for the Bar led by Robin de Wilde and Tony Scrivener had appeared on the scene to sweep the board in Bar Council elections with dissatisfaction at legal aid fee levels its biggest vote-winning issue.

One could summarise what has happened more recently by saying: in first decade of the present century the quality of the legal aid system deteriorated slowly, and in the second decade of the present century it deteriorated fast.

The cost of an area of government spending increasing is understandable if its scope or quality is improving; and a deterioration in quality is understandable if spending is reduced. But with legal aid we have the jaw-dropping phenomenon that even today, after all the cuts in fee levels, in scope and in eligibility, the cost is still three times higher in real terms than in the golden age of 1980. In my opinion there will be no satisfactory reform of our tragically failing access to justice until all concerned frankly address that conundrum.

There are, certainly, several factors in play unrelated to the nature of the legal aid scheme. The costs of all court proceedings have risen over recent decades – worryingly so. Among contributory causes have been the increasing sophistication of expert evidence, and the explosion in the volume of documents owing to digital technologies. In my view another factor has been the Woolf reforms of civil procedure, which under the banner of reducing costs actually greatly increased them. But I find it hard to think that the staggering conundrum of triple cost for worse legal aid service is not partly the result of changes specific to it.

In fact, I believe that two legal aid specific factors have been material. The first is a change in structures. Until 1988 civil legal aid was run by the Law Society. Decisions on difficult applications, or appeals against refusals, were determined by a committee of four lawyers. I served on such a legal aid committee for some years, as did many others. I cannot recall being paid anything for reading the papers in advance or attending the meetings: it was something we did as a service to the profession. Civil legal aid payments were assessed by those who are today called costs judges. In the Crown Court the level of fees were assessed by the court clerks who sat in court.

Today, by contrast, we have a centralised system run by an executive branch of the Ministry of Justice. The ultimate decision-maker on any application is a civil servant, the Director of Legal Aid Casework, who is not required to have any legal qualifications. There is little accountability to taxpayers or Parliament, and no systematic basis for external scrutiny. In the last decade one of the frustrations for criminal practitioners has been having to negotiate with civil servants who have little knowledge of either criminal law or Crown Court practice. In other words, whereas originally decisions were taken by legally qualified professionals and officials with direct knowledge of the court system, now they are taken by unqualified people with no experience of either representing clients or working in the courts.

At the same time there has been a change in culture. One of the big changes on the ground has been the dramatic reduction in the number of firms of solicitors undertaking legal aid work. In the late 20th century most medium sized or high street firms would handle at least a few legal aid cases. Today a normal solicitors’ firm is not allowed to undertake the poorly paid legal aid work even if it were to wish to do so. The LSC carried out a deliberate programme of reducing the number of legal aid providers. In consequence there are legal aid deserts with no legal aid provision for miles around. The Bar has been affected by the shrinking of the fields of work for which civil legal aid is granted. Chancery chambers, personal injury chambers, general common law chambers – these and others have ceased to be places where legal aid cases are sometimes seen. Thus, overall legal aid has largely become an activity for dedicated publicly funded practitioners.

There are many reforms which I should like to see: these include judges being more robust in controlling the length of trials, restoration of the Green Form scheme, and a Contingency Legal Aid Fund.

But over and beyond such reforms, and actual higher spending if it can be wrung out of the Whitehall budgets, I believe that effective radical reform must get to what I see as the root of the problem – the changes in structure and culture. The administration of civil legal aid should be returned to lawyers. I would urge government to undertake a pilot project under which a Circuit in conjunction with local Law Societies would be granted a budget equal to the current spend in its geographical area to run legal aid there. I believe that the legal practitioners could do a better job than the bureaucrats – just as teachers running academy schools do it better than local authorities.

One principle should be that, like trustees, and like the members of the old legal aid committees, the barristers and solicitors who make decisions on the merits of applications would be unpaid. This, in itself, would yield a modest saving, bearing in mind that the civil servants who do this at present are salaried. I suspect that the efficiency savings would be greater, as all concerned come to regard the wise expenditure of the local funds as a serious responsibility to be discharged in accordance with our profession’s own highest standards of care for clients. This could herald a new ethos in legal aid – or, perhaps I should say, a return to the ethos of legal aid’s earlier golden age.

This article is a summary of Reforming Legal Aid – The Next Steps by Anthony Speaight QC (Politeia: April 2022). The full paper can be read here.

* There were two extensions in cover outside of court proceedings, namely attendance by solicitors at police stations, and representation in mental health tribunals, but the costs of these is not such as to modify the picture significantly.

** Figures not necessarily collected on a like-for-like basis over the 20th century and not comparable with RDEL figures for the post-2004/5 period or based, like these, on modern accounting processes. Even with the difficulty of presenting a like-for-like picture, or the high inflation of the 1970s, and lower but consistent inflation in the Thatcher years, these were significant rises. I am most grateful to the Legal Aid Statistics Department for their help in supplying the cash figures and the clear explanation of the difficulties in assessing these. Source: ‘Reforming Legal Aid’, by Sheila Lawlor, Gavin Rice, Jonathan Fisher QC, Max Hardy, Edite Ligere & James Taghdissian, pp1-2.

In the first decade of the 21st century, legal aid was run by a body called the Legal Services Commission (LSC). The LSC had the technical status of a non-departmental public body, which meant that, in contrast to the present Legal Aid Agency, appointments to its board were subject to the principles on public appointments, including advertisement. In 2005 the LSC advertised vacancies for lawyers. Hardly anybody seems to have paid any attention to the advertisement because, a few months later, they advertised again. The then Chair of the Bar, not wanting to miss an opportunity, drew my attention to this and urged me to apply. I duly did so; and set about preparing for the interview.

In the end the LSC found a better suited barrister who had a legal aid practice, which by then I no longer had. But I had a lively hour’s conversation with Sir Michael Barber, the LSC’s then Chairman and a veteran of public bodies, and a couple of officials.

I came away from what proved an interesting episode with two abiding impressions. One was that Whitehall regarded legal aid as if it were a dangerous wild animal they were trying to control. The second was that their attitude was entirely understandable.

What I discovered in my research to prepare for the interview was that legal aid spending resembled a runaway train: I do not believe there is any field of public expenditure which rose as fast as legal aid in the later years of the 20th century. Neither then, nor later, were the facts of how much it had spiraled ever acknowledged by the Bar or the Law Society. So, conversation between the legal profession and government was a dialogue of the deaf.

When retribution ultimately came it turned savage. What started as freezes turned into cuts – not just cuts in money terms, but cuts in real terms (ie after adjustment for inflation). Administration by costs judges, members of the legal profession and experienced Crown Court officials staff turned into administration by bureaucrats who know nothing about the law.

As the years have passed, information on legal aid spending in the 1970s and 1980s has become harder to access. For this reason, as well as lack of interest in the legal professions in statistics which might be helpful to the government, the facts about the actual rise in legal aid spending are not detailed in any publication or paper which I have seen for many years. Not, that is, until March this year.

Now the think tank Politeia has used data from official sources in a publication, Reforming Legal Aid (by Sheila Lawlor, Gavin Rice, Jonathan Fisher QC, Max Hardy, Edite Ligere and James Taghdissia). In an account of 20th century policy, it discusses how the figures changed over the years. It also explains that a different basis was used for data collection in the later decades of the last century and the caveats about this change must be respected in making comparisons. Nonetheless the comparison is so stark that errors at the margin would make no difference of significance to the picture. Transferring raw figures into figures adjusted for inflation so that they can be compared on a broadly like-for-like basis, they show the rise at 2018-19 prices presented on the chart below.

The figures for the years for 1970-1 and earlier years are of limited relevance. It was only during the 1970s that legal aid in the newly established Crown Court was moved from the Home Office, that the Green Form scheme began, that the number of divorces grew, and that legal aid was extended to education, welfare and housing cases.

The two figures which are of most interest are:

So, in those two years the scope was broadly comparable* and yet the cost quadrupled.

That quadrupling might be understandable if the quality of legal aid had in some way improved over that period. But the opposite was the case. Whereas in 1979 nearly 80% of the population were in means test terms within the scope of legal aid, by reason of eligibility changes in 1994 this fell to 50%, and went on falling. And whereas in the late 1970s the rates of legal aid payments for criminal and civil work were found by the Bar to be reasonable, in 1987 the Campaign for the Bar led by Robin de Wilde and Tony Scrivener had appeared on the scene to sweep the board in Bar Council elections with dissatisfaction at legal aid fee levels its biggest vote-winning issue.

One could summarise what has happened more recently by saying: in first decade of the present century the quality of the legal aid system deteriorated slowly, and in the second decade of the present century it deteriorated fast.

The cost of an area of government spending increasing is understandable if its scope or quality is improving; and a deterioration in quality is understandable if spending is reduced. But with legal aid we have the jaw-dropping phenomenon that even today, after all the cuts in fee levels, in scope and in eligibility, the cost is still three times higher in real terms than in the golden age of 1980. In my opinion there will be no satisfactory reform of our tragically failing access to justice until all concerned frankly address that conundrum.

There are, certainly, several factors in play unrelated to the nature of the legal aid scheme. The costs of all court proceedings have risen over recent decades – worryingly so. Among contributory causes have been the increasing sophistication of expert evidence, and the explosion in the volume of documents owing to digital technologies. In my view another factor has been the Woolf reforms of civil procedure, which under the banner of reducing costs actually greatly increased them. But I find it hard to think that the staggering conundrum of triple cost for worse legal aid service is not partly the result of changes specific to it.

In fact, I believe that two legal aid specific factors have been material. The first is a change in structures. Until 1988 civil legal aid was run by the Law Society. Decisions on difficult applications, or appeals against refusals, were determined by a committee of four lawyers. I served on such a legal aid committee for some years, as did many others. I cannot recall being paid anything for reading the papers in advance or attending the meetings: it was something we did as a service to the profession. Civil legal aid payments were assessed by those who are today called costs judges. In the Crown Court the level of fees were assessed by the court clerks who sat in court.

Today, by contrast, we have a centralised system run by an executive branch of the Ministry of Justice. The ultimate decision-maker on any application is a civil servant, the Director of Legal Aid Casework, who is not required to have any legal qualifications. There is little accountability to taxpayers or Parliament, and no systematic basis for external scrutiny. In the last decade one of the frustrations for criminal practitioners has been having to negotiate with civil servants who have little knowledge of either criminal law or Crown Court practice. In other words, whereas originally decisions were taken by legally qualified professionals and officials with direct knowledge of the court system, now they are taken by unqualified people with no experience of either representing clients or working in the courts.

At the same time there has been a change in culture. One of the big changes on the ground has been the dramatic reduction in the number of firms of solicitors undertaking legal aid work. In the late 20th century most medium sized or high street firms would handle at least a few legal aid cases. Today a normal solicitors’ firm is not allowed to undertake the poorly paid legal aid work even if it were to wish to do so. The LSC carried out a deliberate programme of reducing the number of legal aid providers. In consequence there are legal aid deserts with no legal aid provision for miles around. The Bar has been affected by the shrinking of the fields of work for which civil legal aid is granted. Chancery chambers, personal injury chambers, general common law chambers – these and others have ceased to be places where legal aid cases are sometimes seen. Thus, overall legal aid has largely become an activity for dedicated publicly funded practitioners.

There are many reforms which I should like to see: these include judges being more robust in controlling the length of trials, restoration of the Green Form scheme, and a Contingency Legal Aid Fund.

But over and beyond such reforms, and actual higher spending if it can be wrung out of the Whitehall budgets, I believe that effective radical reform must get to what I see as the root of the problem – the changes in structure and culture. The administration of civil legal aid should be returned to lawyers. I would urge government to undertake a pilot project under which a Circuit in conjunction with local Law Societies would be granted a budget equal to the current spend in its geographical area to run legal aid there. I believe that the legal practitioners could do a better job than the bureaucrats – just as teachers running academy schools do it better than local authorities.

One principle should be that, like trustees, and like the members of the old legal aid committees, the barristers and solicitors who make decisions on the merits of applications would be unpaid. This, in itself, would yield a modest saving, bearing in mind that the civil servants who do this at present are salaried. I suspect that the efficiency savings would be greater, as all concerned come to regard the wise expenditure of the local funds as a serious responsibility to be discharged in accordance with our profession’s own highest standards of care for clients. This could herald a new ethos in legal aid – or, perhaps I should say, a return to the ethos of legal aid’s earlier golden age.

This article is a summary of Reforming Legal Aid – The Next Steps by Anthony Speaight QC (Politeia: April 2022). The full paper can be read here.

* There were two extensions in cover outside of court proceedings, namely attendance by solicitors at police stations, and representation in mental health tribunals, but the costs of these is not such as to modify the picture significantly.

** Figures not necessarily collected on a like-for-like basis over the 20th century and not comparable with RDEL figures for the post-2004/5 period or based, like these, on modern accounting processes. Even with the difficulty of presenting a like-for-like picture, or the high inflation of the 1970s, and lower but consistent inflation in the Thatcher years, these were significant rises. I am most grateful to the Legal Aid Statistics Department for their help in supplying the cash figures and the clear explanation of the difficulties in assessing these. Source: ‘Reforming Legal Aid’, by Sheila Lawlor, Gavin Rice, Jonathan Fisher QC, Max Hardy, Edite Ligere & James Taghdissian, pp1-2.

Structural change brought decline in the quality of legal aid at the same time as the cost tripled – it’s time to return the administration to lawyers, argues Anthony Speaight QC

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar