*/

When politicians take aim at judges, it’s more than political theatre – it’s a threat to the rule of law. Judges can’t fight back from the bench, so what options do they have? Peter Oldham KC explores lessons from the past

In January 2025 the Bar Council expressed public concern about reports from members of the Bar who have faced increasing intimidation and threats (see the reports in Counsel magazine, July and October 2025).

This is a problem affecting lawyers in many parts of the world. In May this year, the UK signed the Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of the Profession of Lawyer. Art 6(5) says that, subject to rights of freedom of expression:

‘5. Parties shall ensure that lawyers do not suffer adverse consequences as a result of being identified with their clients or their clients’ cause.’

Judges increasingly face these attacks too. And as the Lady Chief Justice’s 2025 Report to Parliament explained, when politicians berate judges, the risks go beyond encouraging a pile-on from keyboard warriors. The dangers are constitutional. A joint statement from the Bar Council, the Law Society and their Scottish and Northern Irish counterparts on 13 October 2025 took up this theme:

‘... Politically motivated attacks on the legal profession are irresponsible and dangerous. They weaken public trust and confidence in the rule of law and erode the very foundations of justice that underpin fairness and democracy.’

There is a Parliamentary convention that in the course of debate, MPs can criticise judges only on a motion, rather than ad hoc, so that any adverse reflection on a judge in Parliament is subject to fair rules of debate. This is reflected in Erskine May on Parliamentary Practice, which says at para 21.23:

‘... unless the discussion is based upon a substantive motion, drawn in proper terms, reflections must not be cast in debate upon the conduct of... judges of the superior courts of the United Kingdom...’

A famous instance occurred in the Commons on 3 November 1911 during a debate on the Naval Prize Bill, where the criticism consisted of one word. In advocating the excellence of British Prize Courts, Sir Alfred Cripps said (Hansard HC (1911) Vol 30, col 1170):

‘In no country in the civilised world is there more respect for the Courts than there is in the United Kingdom, the reason being that our judges represent no one, but are chosen for their great juridical knowledge and act impartially as regards all interests.’

Joseph King MP interjected: ‘Ridley’. Mr Justice Ridley was described on his death in 1928 by Sir Edward Pollock MR in private correspondence as ‘by general opinion of the Bar the worst High Court judge of our time, ill-tempered and grossly unfair’. King was instantly called out by both Cripps and the Speaker. Just as immediately, King said: ‘I withdraw unreservedly, I regret I made any remark’; and the debate moved on.

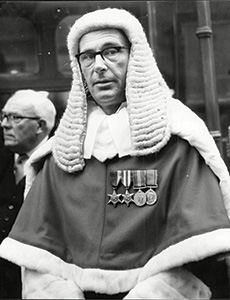

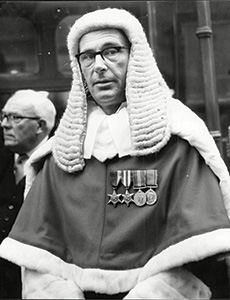

Another very telling episode occurred during the life of the short-lived National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC) from 1971-74. This court was set up by Sir Edward Heath’s Conservative government to police strikes during a period of extreme industrial unrest. The Labour opposition under Harold Wilson were bitterly opposed to Heath’s reforms so the NIRC had to face a campaign of hostility in Parliamentary debates. But numerous MPs showed no compunction in also attacking the NIRC presiding judge, Sir John Donaldson (later to become Master of the Rolls).

In September 1973, Donaldson made a sequestration order against the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers for failing to obey the NIRC’s orders in a case called Con-Mech v AUEW [1973] ICR 620. A month or so later, Donaldson was accused in Commons debates, quite wrongly, of issuing an order deliberately targeting the union’s political fund. Joe Ashton MP said Donaldson was guilty of either:

‘gross incompetence if he did not know where the money came from, and... if he did know... was it not a question of a political fine, or political corruption?’ (Hansard HC Vol 864, cols 27-28).

Efforts were then made to regularise these entirely unwarranted criticisms through adopting appropriate Parliamentary procedures, and a motion calling for Donaldson to go was signed by 94 Labour MPs.

MPs had taken advantage of the immunity which Commons debates gave them. But judges have no such pulpit. What can a judge to do in such circumstances? Should they try to defend themselves, or just take the blows and keep a dignified silence? And if they do speak up to put their case, how can they do it in a way which doesn’t simply inflame the situation? What Donaldson did is a good example of throwing fuel on the fire.

He was due to give a speech in Glasgow about the work of the NIRC, but he used it as a means of trying to rebut MPs’ claims against him. And that led his enemies in the Commons to accuse him of calling Parliamentary proceedings into question in breach of Art 9 of the Bill of Rights (‘... the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament’).

That in turn then led to the Lord Chancellor, Lord Hailsham entering the fray, giving a speech in December sticking up for the judge, and warning that where MPs abused the privilege of Parliament, ‘what salvation for the rule of law?’. The downward spiral continued: MPs then complained that Hailsham had committed contempt of the Commons by trying to control what it could debate. Eventually the matter ran out of political steam. But the story shows what can happen if a judge engages in self-help to rebut criticism.

Leaping forward 40 years, in 2014 Lord Dyson MR gave the Third BAILII Sir Henry Brooke Lecture, entitled ‘Criticism of judges; fair game or off-limits?’. He cautioned against being over-protective of judges, saying that free debate meant they should sometimes have to accept public criticism; but he explained that when a judge was unfairly blamed, and was wondering whether to try to set the record straight, there were different possibilities.

One was to say nothing: as Lord Kilmuir’s said in his so-called ‘Rules’ of 1955: ‘So long as a judge keeps silent his reputation for wisdom and impartiality remains unassailable.’ But Lord Dyson believed this convention to have faded in recent decades. Another way forward was for the judge to make a personal response, but he thought that this could give ‘the appearance of the judge being an active participant in a political conversation, rather than a neutral administrator of the law’.

Lord Dyson’s preferred solution was ‘an institutional approach’, involving a response from the Lady Chief Justice or Judicial Press Office. The current Guide to Judicial Conduct expands on this approach, explaining that it’s generally best for judges not to comment ‘on matters of controversy or those that are for Parliament or Government’ but that on occasion ‘cautious engagement is possible’, through the Lady Chief Justice and some other leadership judges, with the support of the Press Office.

So there are options available now which were not available in 1973.

But the dangers to the rule of law which arise when judges are criticised unfairly by politicians are greater than ever in the megaphone-era of social media and instant news reaction.

Sir John Donaldson (later to become Master of the Rolls) is a good example of throwing fuel on the fire... the story shows what can happen if a judge engages in self-help to rebut criticism.

‘Council of Europe treaty to protect lawyers’, Sarah Kavanagh, Counsel July 2025

‘Standing up for lawyers’, Sarah Kavanagh, Counsel December 2025

‘Vilifying lawyers puts them at risk’, Bar Council and Law Society Joint Statement, 13 October 2025

The Lady Chief Justice’s Report 2025

‘Criticism of judges: fair game or off-limits?’, the Third BAILII Sir Henry Brooke Lecture, Lord Dyson, Master of the Rolls, 27 November 2014

In January 2025 the Bar Council expressed public concern about reports from members of the Bar who have faced increasing intimidation and threats (see the reports in Counsel magazine, July and October 2025).

This is a problem affecting lawyers in many parts of the world. In May this year, the UK signed the Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of the Profession of Lawyer. Art 6(5) says that, subject to rights of freedom of expression:

‘5. Parties shall ensure that lawyers do not suffer adverse consequences as a result of being identified with their clients or their clients’ cause.’

Judges increasingly face these attacks too. And as the Lady Chief Justice’s 2025 Report to Parliament explained, when politicians berate judges, the risks go beyond encouraging a pile-on from keyboard warriors. The dangers are constitutional. A joint statement from the Bar Council, the Law Society and their Scottish and Northern Irish counterparts on 13 October 2025 took up this theme:

‘... Politically motivated attacks on the legal profession are irresponsible and dangerous. They weaken public trust and confidence in the rule of law and erode the very foundations of justice that underpin fairness and democracy.’

There is a Parliamentary convention that in the course of debate, MPs can criticise judges only on a motion, rather than ad hoc, so that any adverse reflection on a judge in Parliament is subject to fair rules of debate. This is reflected in Erskine May on Parliamentary Practice, which says at para 21.23:

‘... unless the discussion is based upon a substantive motion, drawn in proper terms, reflections must not be cast in debate upon the conduct of... judges of the superior courts of the United Kingdom...’

A famous instance occurred in the Commons on 3 November 1911 during a debate on the Naval Prize Bill, where the criticism consisted of one word. In advocating the excellence of British Prize Courts, Sir Alfred Cripps said (Hansard HC (1911) Vol 30, col 1170):

‘In no country in the civilised world is there more respect for the Courts than there is in the United Kingdom, the reason being that our judges represent no one, but are chosen for their great juridical knowledge and act impartially as regards all interests.’

Joseph King MP interjected: ‘Ridley’. Mr Justice Ridley was described on his death in 1928 by Sir Edward Pollock MR in private correspondence as ‘by general opinion of the Bar the worst High Court judge of our time, ill-tempered and grossly unfair’. King was instantly called out by both Cripps and the Speaker. Just as immediately, King said: ‘I withdraw unreservedly, I regret I made any remark’; and the debate moved on.

Another very telling episode occurred during the life of the short-lived National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC) from 1971-74. This court was set up by Sir Edward Heath’s Conservative government to police strikes during a period of extreme industrial unrest. The Labour opposition under Harold Wilson were bitterly opposed to Heath’s reforms so the NIRC had to face a campaign of hostility in Parliamentary debates. But numerous MPs showed no compunction in also attacking the NIRC presiding judge, Sir John Donaldson (later to become Master of the Rolls).

In September 1973, Donaldson made a sequestration order against the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers for failing to obey the NIRC’s orders in a case called Con-Mech v AUEW [1973] ICR 620. A month or so later, Donaldson was accused in Commons debates, quite wrongly, of issuing an order deliberately targeting the union’s political fund. Joe Ashton MP said Donaldson was guilty of either:

‘gross incompetence if he did not know where the money came from, and... if he did know... was it not a question of a political fine, or political corruption?’ (Hansard HC Vol 864, cols 27-28).

Efforts were then made to regularise these entirely unwarranted criticisms through adopting appropriate Parliamentary procedures, and a motion calling for Donaldson to go was signed by 94 Labour MPs.

MPs had taken advantage of the immunity which Commons debates gave them. But judges have no such pulpit. What can a judge to do in such circumstances? Should they try to defend themselves, or just take the blows and keep a dignified silence? And if they do speak up to put their case, how can they do it in a way which doesn’t simply inflame the situation? What Donaldson did is a good example of throwing fuel on the fire.

He was due to give a speech in Glasgow about the work of the NIRC, but he used it as a means of trying to rebut MPs’ claims against him. And that led his enemies in the Commons to accuse him of calling Parliamentary proceedings into question in breach of Art 9 of the Bill of Rights (‘... the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament’).

That in turn then led to the Lord Chancellor, Lord Hailsham entering the fray, giving a speech in December sticking up for the judge, and warning that where MPs abused the privilege of Parliament, ‘what salvation for the rule of law?’. The downward spiral continued: MPs then complained that Hailsham had committed contempt of the Commons by trying to control what it could debate. Eventually the matter ran out of political steam. But the story shows what can happen if a judge engages in self-help to rebut criticism.

Leaping forward 40 years, in 2014 Lord Dyson MR gave the Third BAILII Sir Henry Brooke Lecture, entitled ‘Criticism of judges; fair game or off-limits?’. He cautioned against being over-protective of judges, saying that free debate meant they should sometimes have to accept public criticism; but he explained that when a judge was unfairly blamed, and was wondering whether to try to set the record straight, there were different possibilities.

One was to say nothing: as Lord Kilmuir’s said in his so-called ‘Rules’ of 1955: ‘So long as a judge keeps silent his reputation for wisdom and impartiality remains unassailable.’ But Lord Dyson believed this convention to have faded in recent decades. Another way forward was for the judge to make a personal response, but he thought that this could give ‘the appearance of the judge being an active participant in a political conversation, rather than a neutral administrator of the law’.

Lord Dyson’s preferred solution was ‘an institutional approach’, involving a response from the Lady Chief Justice or Judicial Press Office. The current Guide to Judicial Conduct expands on this approach, explaining that it’s generally best for judges not to comment ‘on matters of controversy or those that are for Parliament or Government’ but that on occasion ‘cautious engagement is possible’, through the Lady Chief Justice and some other leadership judges, with the support of the Press Office.

So there are options available now which were not available in 1973.

But the dangers to the rule of law which arise when judges are criticised unfairly by politicians are greater than ever in the megaphone-era of social media and instant news reaction.

Sir John Donaldson (later to become Master of the Rolls) is a good example of throwing fuel on the fire... the story shows what can happen if a judge engages in self-help to rebut criticism.

‘Council of Europe treaty to protect lawyers’, Sarah Kavanagh, Counsel July 2025

‘Standing up for lawyers’, Sarah Kavanagh, Counsel December 2025

‘Vilifying lawyers puts them at risk’, Bar Council and Law Society Joint Statement, 13 October 2025

The Lady Chief Justice’s Report 2025

‘Criticism of judges: fair game or off-limits?’, the Third BAILII Sir Henry Brooke Lecture, Lord Dyson, Master of the Rolls, 27 November 2014

When politicians take aim at judges, it’s more than political theatre – it’s a threat to the rule of law. Judges can’t fight back from the bench, so what options do they have? Peter Oldham KC explores lessons from the past

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar