*/

The Bar is in danger of losing its distinct legal heritage, warns Clare Cowling – who outlines the considerable research value to be found in chambers records

‘There is a general lack of knowledge about the Bar, with misconceived notions of what barristers do, how they work and their professional interaction with the solicitor branch and the public… Although much of barristers’ work takes place in public courtrooms, much also remains hidden from view, with many working in the cloistered surroundings of the Inns of Court or in chambers across the provinces.’ So delegates heard at last year’s Being Human festival: the ‘Humanity of Lawyers’ in a session focusing on the work of the Bar.

Does the Bar want its heritage to remain hidden? Our legal framework has been affected by developments including changes to legal services, globalisation and digital obsolescence, but no concerted effort has, as yet, been made to protect and preserve the records which document these changes. The Legal Records at Risk project, led by the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies and working in collaboration with the legal profession, research institutions and archives, including The National Archives and the British Records Association, seeks to develop a national strategy to identify and preserve our legal heritage and to save modern (ie 20th and 21st century) private sector legal records in the UK that may be at risk.

All records in the private sector face similar challenges, but modern legal records are particularly vulnerable due to factors transforming the nature, organisation, regulation and economics of legal services.Additionally, unless systematic efforts are made towards collecting private sector legal records, research using modern legal records will continue to be weighted towards the study of government policy, legislation and the courts, producing a government-centric historical picture of the UK’s legal framework.In short, we are in danger of losing a significant proportion of our legal heritage.

Our initial findings indicate that the records of individual barristers and barristers’ chambers are particularly at risk. The National Archives’ Discovery portal (discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk) lists only five sets of 20th century barristers’ chambers papers in local archives and 152 entries for the papers of individual barristers, as opposed to 986 entries for the business records of law firms and 1,368 entries for solicitors (though some barristers will alternatively be listed under future occupations such as judges). Papers usually comprise correspondence, diaries and fee books. Some are classified as ‘legal case notes’ which may or may not contain confidential material. Does the Bar wish to continue to be historically under-represented in this way?

Chambers

The Bar Standards Board Handbook (p 65) states:

‘When deciding how long records need to be kept, you will need to take into consideration various requirements, such as those of this Handbook (see, for example, Rules C108, C129 and C141), the Data Protection Act and HM Revenue and Customs. You may want to consider drawing up a Records Keeping policy to ensure that you have identified the specific compliance and other needs of your practice.’

The Institute of Barristers’ Clerks (IBC) also gives guidance on what records should be created and kept by chambers’ clerks, including annual reports and accounts, descriptions of chambers’ work and records of instructions, briefs and fees (see IBC Code of Conduct, Appendix A).

Individual barristers

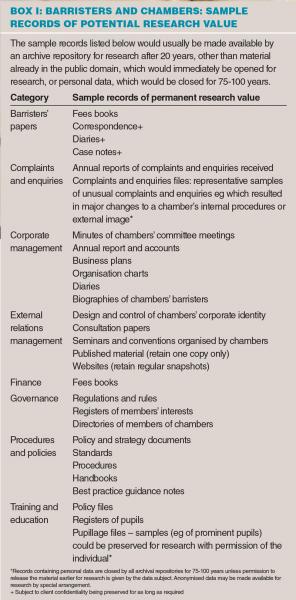

The Handbook advises barristers to destroy their copies of case papers after six to seven years (C129 and C141), although in the case of lay clients they are entitled to copy all documents received and to retain such copies permanently (C131). Presumably these papers are stored either in chambers or in barristers’ own homes. It is clear, therefore, that chambers and individual barristers hold information of considerable potential research value which could and should be kept securely and preserved for posterity (see box I below for a sample list). Any action to preserve such records would of course have to take into account client confidentiality (see box II below).

The Code of Conduct clearly states that client and complaints information are to be kept confidential. The Handbook states:

S12: ‘The regulatory objectives of the Bar Standards Board derive from the Legal Services Act 2007 and can be summarised as follows… that the affairs of clients are kept confidential.’

rC106: ‘All communications and documents relating to complaints must be kept confidential.’

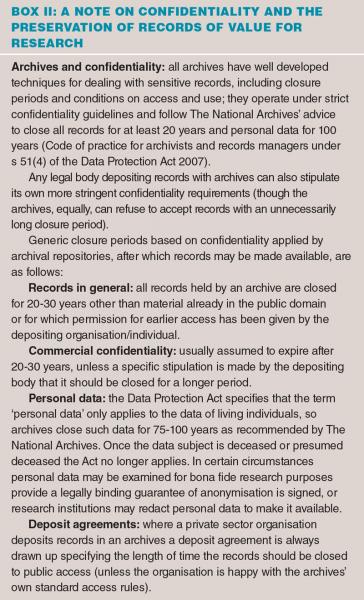

The question is whether this guarantee of confidentiality is in perpetuity or for a limited (in archival terms) period. The Code of Conduct does not specify a length of time, so the next question is whether there is a tacit assumption of confidentiality in perpetuity, and whether this has ever been challenged. The expiry date for legal professional privilege is also a grey area and one reason why client case files are not usually offered to, or accepted by, archives unless they are at least several hundred years old. It is time and more that the legal profession clarified exactly how long it expects client confidentiality to last (see box II).

We have been in touch with the Inns of Court archivists and librarians to seek support for the project – all have offered support in principle despite their limited resources and an article has been published in the Inner Temple e-newsletter.

An agreement has been made with the London Metropolitan Archives to accept legal records of historical value of London-based legal entities identified by the project.

In partnership with the British Records Association and The National Archives, we are also developing a consistent model for the rescue of the records of legal entities and practitioners outside London.

Seeking to engage the interest of barristers and practice managers, we are appealing not only to your sense of the potential historical value of Bar records but to your understanding of the importance of letting the public know what you do and how you do it, so that they in turn will have a more accurate grasp of the importance of your work and its value to the community.

Greater transparency and public engagement through the eventual release of records for research should enhance the profession’s public-facing image and help address the issues raised above, not least to challenge some public perceptions about the Bar. There are other benefits, too, in terms of cost savings for chambers (eg reduced storage space and more efficient records management).

The Legal Records at Risk project will:

Quite simply, if you hold any of the records referred to in this article and agree that there is an argument for preserving them for posterity, not least to enhance the reputation of the Bar, please contact the Legal Records at Risk Project Director, Clare Cowling at clare.cowling@sas.ac.uk.

Contributor Clare Cowling, Associate Research Fellow and Project Director, Legal Records at Risk project, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, University of London.

‘There is a general lack of knowledge about the Bar, with misconceived notions of what barristers do, how they work and their professional interaction with the solicitor branch and the public… Although much of barristers’ work takes place in public courtrooms, much also remains hidden from view, with many working in the cloistered surroundings of the Inns of Court or in chambers across the provinces.’ So delegates heard at last year’s Being Human festival: the ‘Humanity of Lawyers’ in a session focusing on the work of the Bar.

Does the Bar want its heritage to remain hidden? Our legal framework has been affected by developments including changes to legal services, globalisation and digital obsolescence, but no concerted effort has, as yet, been made to protect and preserve the records which document these changes. The Legal Records at Risk project, led by the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies and working in collaboration with the legal profession, research institutions and archives, including The National Archives and the British Records Association, seeks to develop a national strategy to identify and preserve our legal heritage and to save modern (ie 20th and 21st century) private sector legal records in the UK that may be at risk.

All records in the private sector face similar challenges, but modern legal records are particularly vulnerable due to factors transforming the nature, organisation, regulation and economics of legal services.Additionally, unless systematic efforts are made towards collecting private sector legal records, research using modern legal records will continue to be weighted towards the study of government policy, legislation and the courts, producing a government-centric historical picture of the UK’s legal framework.In short, we are in danger of losing a significant proportion of our legal heritage.

Our initial findings indicate that the records of individual barristers and barristers’ chambers are particularly at risk. The National Archives’ Discovery portal (discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk) lists only five sets of 20th century barristers’ chambers papers in local archives and 152 entries for the papers of individual barristers, as opposed to 986 entries for the business records of law firms and 1,368 entries for solicitors (though some barristers will alternatively be listed under future occupations such as judges). Papers usually comprise correspondence, diaries and fee books. Some are classified as ‘legal case notes’ which may or may not contain confidential material. Does the Bar wish to continue to be historically under-represented in this way?

Chambers

The Bar Standards Board Handbook (p 65) states:

‘When deciding how long records need to be kept, you will need to take into consideration various requirements, such as those of this Handbook (see, for example, Rules C108, C129 and C141), the Data Protection Act and HM Revenue and Customs. You may want to consider drawing up a Records Keeping policy to ensure that you have identified the specific compliance and other needs of your practice.’

The Institute of Barristers’ Clerks (IBC) also gives guidance on what records should be created and kept by chambers’ clerks, including annual reports and accounts, descriptions of chambers’ work and records of instructions, briefs and fees (see IBC Code of Conduct, Appendix A).

Individual barristers

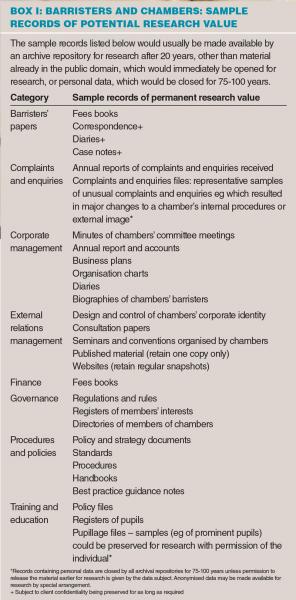

The Handbook advises barristers to destroy their copies of case papers after six to seven years (C129 and C141), although in the case of lay clients they are entitled to copy all documents received and to retain such copies permanently (C131). Presumably these papers are stored either in chambers or in barristers’ own homes. It is clear, therefore, that chambers and individual barristers hold information of considerable potential research value which could and should be kept securely and preserved for posterity (see box I below for a sample list). Any action to preserve such records would of course have to take into account client confidentiality (see box II below).

The Code of Conduct clearly states that client and complaints information are to be kept confidential. The Handbook states:

S12: ‘The regulatory objectives of the Bar Standards Board derive from the Legal Services Act 2007 and can be summarised as follows… that the affairs of clients are kept confidential.’

rC106: ‘All communications and documents relating to complaints must be kept confidential.’

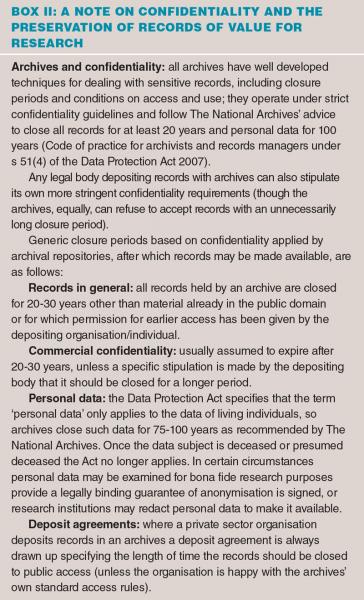

The question is whether this guarantee of confidentiality is in perpetuity or for a limited (in archival terms) period. The Code of Conduct does not specify a length of time, so the next question is whether there is a tacit assumption of confidentiality in perpetuity, and whether this has ever been challenged. The expiry date for legal professional privilege is also a grey area and one reason why client case files are not usually offered to, or accepted by, archives unless they are at least several hundred years old. It is time and more that the legal profession clarified exactly how long it expects client confidentiality to last (see box II).

We have been in touch with the Inns of Court archivists and librarians to seek support for the project – all have offered support in principle despite their limited resources and an article has been published in the Inner Temple e-newsletter.

An agreement has been made with the London Metropolitan Archives to accept legal records of historical value of London-based legal entities identified by the project.

In partnership with the British Records Association and The National Archives, we are also developing a consistent model for the rescue of the records of legal entities and practitioners outside London.

Seeking to engage the interest of barristers and practice managers, we are appealing not only to your sense of the potential historical value of Bar records but to your understanding of the importance of letting the public know what you do and how you do it, so that they in turn will have a more accurate grasp of the importance of your work and its value to the community.

Greater transparency and public engagement through the eventual release of records for research should enhance the profession’s public-facing image and help address the issues raised above, not least to challenge some public perceptions about the Bar. There are other benefits, too, in terms of cost savings for chambers (eg reduced storage space and more efficient records management).

The Legal Records at Risk project will:

Quite simply, if you hold any of the records referred to in this article and agree that there is an argument for preserving them for posterity, not least to enhance the reputation of the Bar, please contact the Legal Records at Risk Project Director, Clare Cowling at clare.cowling@sas.ac.uk.

Contributor Clare Cowling, Associate Research Fellow and Project Director, Legal Records at Risk project, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, University of London.

The Bar is in danger of losing its distinct legal heritage, warns Clare Cowling – who outlines the considerable research value to be found in chambers records

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar