*/

HHJ Nott continues her ground-breaking series with an analysis of 2019/20 publicly funded criminal/civil instructions and newly released profession-wide data, as the Bar is called upon to ‘confront, not hide’ the shocking discrepancies in pay and access to work between male and female barristers

Women at the Bar have for some years expressed concerns surrounding equality of remuneration and opportunity. Although there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of gender discrimination – conscious and unconscious – efforts to assess and address the perceived inequalities have been hampered by lack of direct evidence to either support or undermine the validity of the concerns.

This began to change in July 2017 when Public Law published ‘Patronising Lawyers? Homophily and Same-Sex Litigation Teams before the UK Supreme Court’, an academic paper which examined the gender of advocates appearing in the Supreme Court. Its methodology and evidenced conclusions suggested significant gender disparity in instruction, largely resulting from sponsorship of junior male barristers by senior male barristers. This prompted the Bar Council’s Equality, Diversity and Social Mobility (EDSM) Committee to commission a study into gender and fair access, which as a committee member at the time, I led. The resultant 2018 report was subsequently published in Counsel magazine across two issues. I was asked to revisit the subject in 2019 for Counsel’s edition commemorating 100 years of women at the Bar.

I was able to analyse the earnings by gender at the criminal Bar with the assistance of detailed records held and shared by the Legal Aid Agency (LAA) and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS); earnings in the family and civil jurisdictions remained largely opaque. In 2019, The Lawyer magazine produced some empirical evidence through its litigation tracker of commercial Bar data, revealing that the most active commercial litigation firms instructed a total of 810 barristers of whom only 19% were women. It also provided some evidence of significant disparity in instruction and remuneration within the Employment Appeals Tribunal.

Since then, in August 2020 The Lawyer investigated the instruction patterns of the top 50 disputes firms by revenue over the period July 2019-2020. That study found that Kirkland & Ellis, Travers Smith and Dentons instructed no female barristers on cases that reached judgment in that period. A further 20 firms in the top 50 allocated less than 20% of instructions to female barristers; the top 50 firm that instructed female barristers most frequently on cases that reached judgment was DAC Beachcroft, sending 27% of its instructions to women. Evidence of gender disparity in specific practice areas was beginning to mount. However, without comprehensive income data and analysis across all practice areas, the scale of the problem profession-wide could not be fully assessed. If the extent of the problem is unknown, it is difficult to address.

Towards the end of 2020 and for the first time, the Bar Standards Board (BSB) and the Bar Council each published empirical evidence of the gap in earnings by gender across the profession, with the BSB also publishing information about the ethnicity gap.

Every barrister must apply annually for practice certificate renewal, and in their application must specify their areas of practice in percentage terms, and their income for the previous year (within income brackets). In November 2020 the BSB published Income at the Bar by Gender and Ethnicity. This report, through analysis of barristers’ declared gross income in 2018, disclosed obvious inequalities. According to the BSB, in 2018 35% of the female Bar had a gross income of £60,000 or less, compared to 22% of the male Bar. 38% of male barristers grossed more than £150,000 compared to 18% of female barristers. While women now comprise 38% of the Bar as a whole, they make up 46% of barristers under 15 years’ call and 33% of barristers above 15 years’ call. The BSB found that 38% of female barristers under 15 years’ call had a gross income of less than £60,000; 26% of male barristers under 15 years’ call were in that income bracket. At the higher end, 13% of female barristers under 15 years’ call declared a gross income of more than £150,000, compared to 28% of male barristers.

Looking at those in silk, the BSB found little observable pattern for those earning under £90,000. However, in the higher income brackets there were notable differences: 66% of female QCs earned between £90,000 and £500,000, compared to 48% of male QCs. In contrast, 34% of male QCs had an income of more than £500,000 compared to 25% of female QCs.

In the same week the BSB issued its report based on 2018 figures, the Bar Council released a Table of Earnings by Gender reflecting the 2019 practice certificate declarations. It reveals continuing inequality at the Bar across all areas of legal practice, which it breaks down into 30 separate practice areas. For the first time, empirical evidence is available in respect of the whole profession.

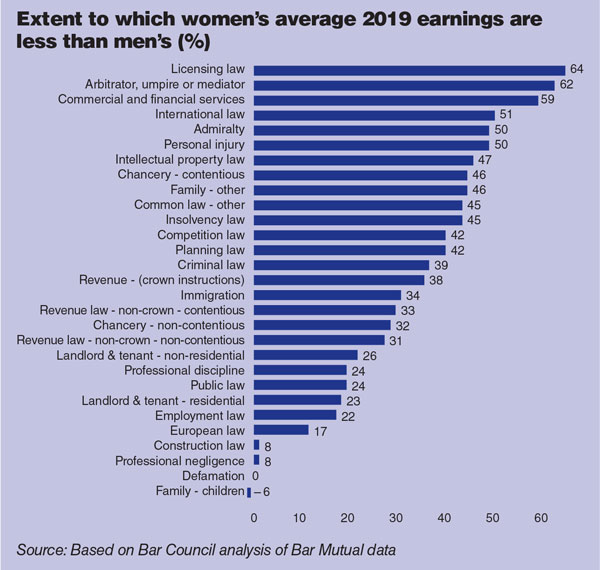

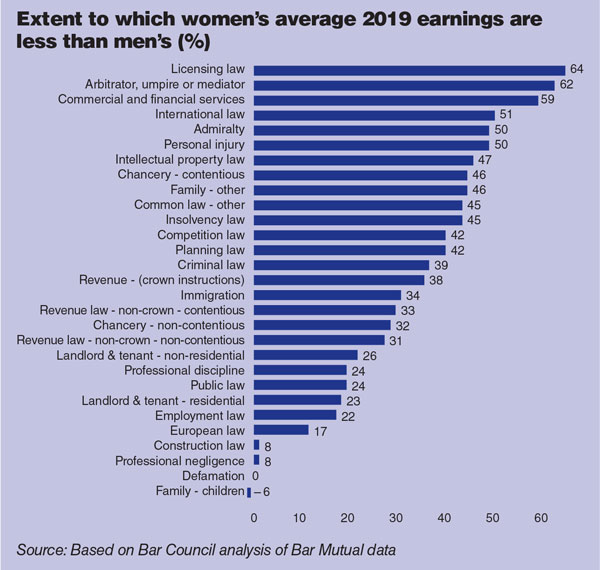

In addition to its published table, the Bar Council has shared with chambers further unpublished extrapolations of its data showing the average difference in 2019 earnings between men and women in different practice areas. As the bar chart below shows, defamation was the only practice area in which there was parity, with women conducting 28% of the work and receiving 28% of the income.

There was one practice area out of the 30 defined by the Bar Council in which women earned on average more than men: in ‘family (children)’ they earned 6% more than their male counterparts. However, in ‘family (other)’ they earned 46% less than men.

The figures come with caveats: the Bar Council states that neither its Table nor the extrapolations set out above, ‘reflect seniority or working patterns so can’t be interpreted as showing that women and men in comparable situations are necessarily being paid differently…[however] these figures demonstrate that we are a long way off equality at the Bar’.

However, in relation to the criminal Bar, Rose Holmes, Research Manager at the Bar Council told me: ‘The Bar Council’s forthcoming joint analysis with the Ministry of Justice of the fee income of publicly funded criminal barristers 2015-2019 (currently confidential under a data-sharing agreement) but to be published soon, confirms a systemic pattern of women barristers earning less than their male counterparts, even when seniority and case volume are taken into account. This disparity is amplified when race and gender are considered together, with Black women earning less than any other group at the criminal Bar.’

The 2020 Chair of the Bar Council, Amanda Pinto QC has described the discrepancies in pay between male and female barristers as ‘shocking’ and has called for the Bar to ‘confront, not hide, this profession-wide problem’.

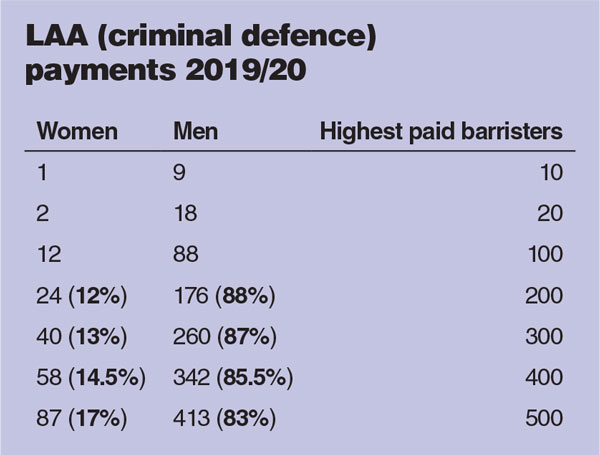

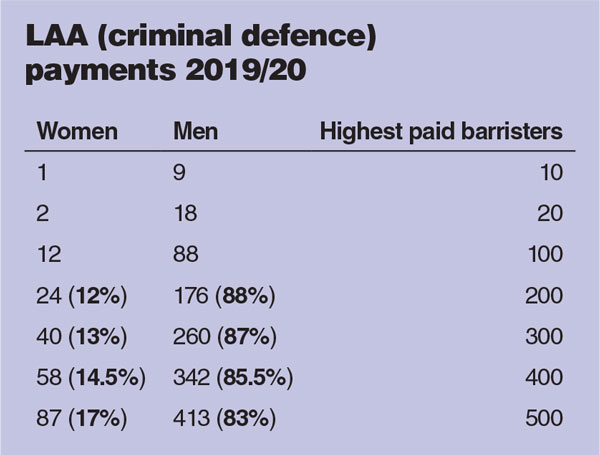

In light of the Bar Council and BSB figures, and ahead of the forthcoming Bar Council and Ministry of Justice joint analysis of publicly funded criminal fee income by gender and ethnicity, I returned to the CPS and LAA who were again kind enough to provide their data for publicly funded work for the year ending March 2019. There is comparatively little private work in crime, so these figures give good insight into access to work across the jurisdiction. This will be the last year in which figures are unaffected by the pandemic. Anyone hoping for an improvement on previous years will be disappointed.

These figures mirror very closely those of last year; if anything, they are very slightly down.

Like the defence figures, CPS payments are down on last year, when there were 102 women in top 500 fee-earners from CPS, 19 women in top 100 and 37 in top 200.

I spoke to Michael Hoare, a senior court business adviser at the CPS who is working with the Bar Council and Women in Criminal Law (WICL) to address the problem of gender inequality. He told me that internally the CPS has strong equality policies and that women comprise 37% of the 248 crown advocates employed by the CPS nationwide – broadly in line with the proportion of women practising at the Bar. Further, across all CPS lawyer grades, the percentage of female employees increases to 62%. Just over a third of CPS lawyers are barristers.

My 2019 report concluded: ‘The CPS operates an equal opportunities policy in-house; will it now also require gender-diverse lists from chambers at all prosecuting grades? Whether or not the criminal Bar as an entity is prepared to tolerate inequity, its main paymaster is unlikely to for much longer.’ I was unaware at the time, but partly as a result of the 2018 EDSM report published in Counsel, the CPS was already taking a close look at how it was ensuring gender equality when instructing advocates externally. Throughout 2020 a steering-group chaired by CPS CEO Rebecca Lawrence with representatives from the CBA and the Bar Council, undertook a review of CPS data which reveals:

Mr Hoare described the gender discrepancy in these areas, in the context of the available pool, as ‘significant’; he emphasised the importance of looking beyond the data – eg that 85% of all fees in respect of high value frauds were paid to men, notwithstanding that 24% of level 3 and 4 counsel on the CPS Specialist Fraud Panel are female – and engaging with the Bar better to understand the reasons why.

Based on the data, the CPS is taking forward a number of actions, which Rebecca Lawrence has set out in a recent blog for Bar Talk (25 November 2020), and which include the following:

Progress against these actions will be monitored by the CPS-Bar Steering Group. The above data gives a national picture; Mr Hoare told me that there are differences between Circuits. For example, on the Northern Circuit there are only three female silks practising crime and only one of those prosecutes regularly. The absence of a diverse cadre of advocates available for CPS work on some Circuits is a topic of discussion with Circuit leaders and has led in some circumstances to the CPS instructing off-Circuit in order to achieve diversity. The CPS will soon publish its new five-year advocacy strategy, covering both in-house and external advocacy, which will place particular emphasis on diversity and inclusion.

Katy Thorne QC, Founder and Chair of WICL commented, ‘These [2018-19] figures confirm WICL’s own research on equal pay gathered from a number of chambers. Sadly, women just don’t get a fair crack at the whip. That’s why we were really pleased to sit down with the CPS and challenge them on their own briefing figures. We are delighted they are now working with us to improve. It proves that without clear statistics and data even the most progressive of organisations will unknowingly perpetuate the existing inequalities in briefing. It’s vital that everyone from chambers to instructing solicitors to the LAA do their own number crunching and ensure that briefing practices are not gender skewed and that barristers in the criminal courts from top to bottom reflect society as a whole.’

Mr Hoare also raised the need for chambers management committees to be alive to – and address – the issue within individual sets. I asked him if he had any thoughts on the effect that the historical lack of diversity in clerks’ rooms may be having. He told me that currently only three of the 48 London chambers doing criminal work has a female senior clerk. He points to a specific issue surrounding late returns, stating that the focus is on getting the work covered at short notice, sometimes at the expense of ensuring the fair allocation of cases across all protected characteristics. Moving forwards, the CPS will be re-emphasising the importance of this – to both chambers and their own staff – and monitoring the protected characteristics of those it instructs, and accepts on return, much more closely to ensure that it achieves greater diversity.

So, the CPS is now alive to the issue and is taking positive action. What of other government departments? Gender diversity, or the lack thereof, in government instructions was brought into stark and public focus during the Article 50 litigation. An outsider looking at live video footage of the all-male counsel teams instructed by the UK government, the Welsh government and the Attorney General for Northern Ireland to present the Supreme Court arguments in the most high profile and constitutionally important legal action of the century to date might reasonably have inferred that the Bar was as male dominated in 2019 as it was in 1919.

I asked the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) why the UK government has only instructed men in the Brexit-related constitutional litigation to date (by which I meant the Article 50 litigation and the Prorogation case). The AGO responded: ‘Both men and women were initially considered, but because of issues of suitability and availability, the counsel team ended up being wholly male. However, GLD and the AG certainly recognise the benefit to female counsel in appearing in high profile cases and realise that given the breadth of talent among female members of the panel and is silk it is only natural that they should be instructed in such cases. We expect this to happen more frequently in the future. For example, two female A panellists have recently been conducting our important C-19 cases.’ I would venture to suggest that the obvious benefit of female counsel appearing in high-profile cases extends beyond the particular counsel concerned and is vital for democracy and wider society. Anyone doubting that proposition only need look at the sea change in the focus of House of Lords and then Supreme Court decisions – and in the consequent development of the law – over the 25 years that our final court of appeal had the benefit of Lady Hale.

I asked a number of questions surrounding gender diversity of the AGO, the Government Legal Department (GLD) and the Counsel General to the Welsh Government, and I am grateful to each organisation for agreeing to provide me with the gender information I sought without my having to make a formal request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. GLD administers the Panel Counsel system on behalf of the Attorney General, and so Simon Harker of GLD responded on behalf of both GLD and the Attorney General.

I asked both the Welsh government and GLD how many men and women had been appointed to their panels of counsel.

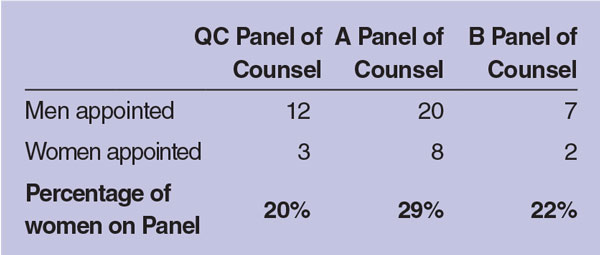

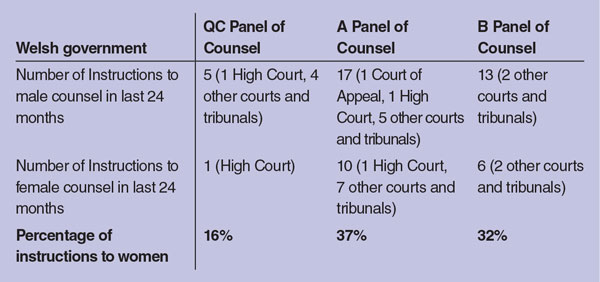

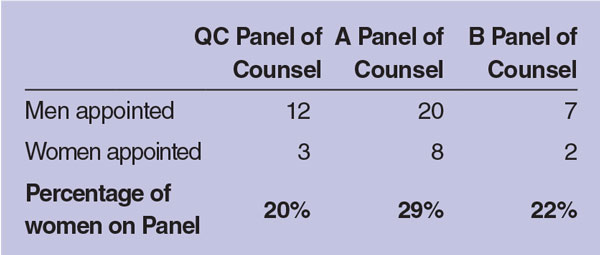

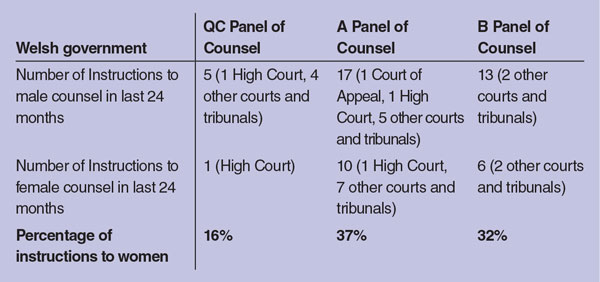

The Welsh government does not have a C Panel of counsel; however, unlike the Attorney General it does operate an appointments process for its panel of QCs. The figures are broken down in the table below:

Only 25% of barristers appointed to Welsh government counsel panels, and therefore able to accept government instructions, are female. It is particularly surprising to see female barristers so poorly represented in the panels of junior counsel.

On behalf of the GLD and Attorney General’s Office, Mr Harker told me: ‘Successive Law Officers have been keen to advance equality of opportunity between men and women at the Bar and the panels have been seen as a way of achieving this.’

The GLD runs London and Regional Panels for EU and civil work carried out on behalf of the UK government. There has never been a female Treasury Devil (or female First Treasury Counsel). The GLD says: ‘There is no reason why Sir James’ successor should not be female. The appointment process will be in accordance with equal opportunities, the law and best practice.’ The next appointment will almost certainly come from the Attorney General’s QC Panel. I was not provided with data surrounding the QC Panel’s composition on the basis that this ‘is simply a list of QCs who have acted for the Government in the past or have indicated… a willingness to act for the Government in the future. There is no selection process. A QC just asks to have his or her name added.’

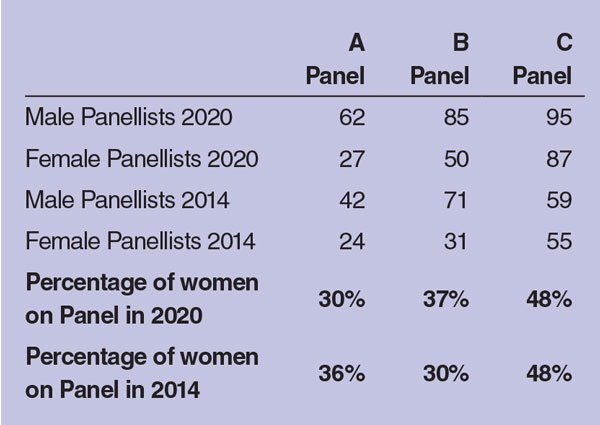

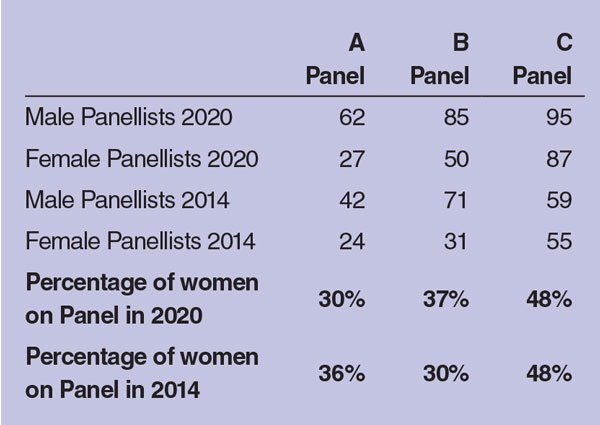

However, I was given detailed data for the current London A, B and C Panels, and also for the A, B and C Panels in 2014. The position for the A Panel is now significantly worse than it was in 2014, the position for the B Panel has improved, and the position for the C Panel has not changed. It is unclear why the female C Panellists of 2014 do not seem to have become the A and B Panellists of 2020.

London Panel figures:

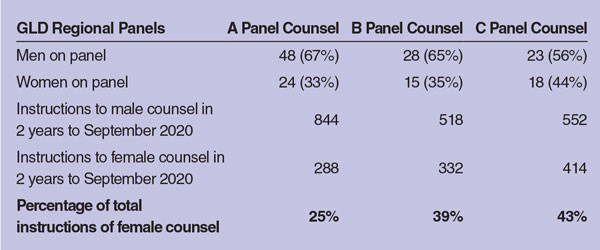

I was also provided with detailed data regarding the gender breakdown on the Regional A, B and C Panels. The position is similar to that of the national panels and is set out in the table in the section below.

I asked both the Welsh government and GLD how many times men and women had been instructed in the last 24 months, in which courts (from the European Court of Justice down to other courts and tribunals) and in what capacity (leader, sole counsel, led junior, etc).

The Welsh government was able to provide me with detailed data on this, which is set out below. The data showed that although women are poorly represented on all panels, those on the A and B Panels actually received per capita more instructions than the men, while the male QCs were allocated more work proportionately than the female silks.

Disappointingly GLD was unable to provide me with equivalent data for the male and female barristers they instruct, although some of this information must be a matter of public record available on platforms such as BAILII. I was told that GLD does ‘not keep central records which go down to the level of detail of who has been instructed in which type of court or who has been led or not’. I was not told why it does not keep such records.

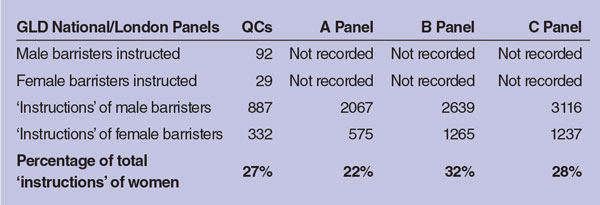

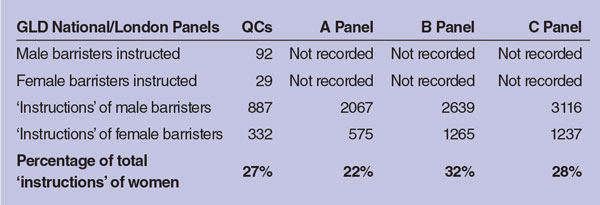

However, GLD was able to provide me with data about the number of men and women who have invoiced them over 24 month periods (24 months to June 2020 for QCs and 1 September to 31 August for A, B and C Panels) and the number of instructions in relations to which they invoiced. The GLD records instructions as cases invoiced per quarter. If a barrister invoices on a single case four times in one quarter that is recorded as one ‘instruction’. If she invoices on that same case once per quarter over a year, that is recorded as four ‘instructions’. Accordingly, ‘instructions’ are not individual cases, nor are they individual invoices but rather a hybrid of the two. That data showed the following:

It is particularly striking that on the C Panel where female barristers comprise 48% of barristers on the Panel, 72% of GLD’s ‘instructions’ went to male barristers. Most C Panel members are under 10 years’ call, typically appointed in their mid to late twenties. It seems unlikely that the significant disparity in work allocation at this most junior level should all be attributable to lifestyle decisions, or maternity leave. At the more senior level, not only has the A Panel increased by seven men to every woman since 2014, the 30% of A panellists who are female received only 22% of the ‘instructions.’ While both GLD and the Welsh government said that they were keen to encourage more women to join their panels, female counsel might be reluctant to join a panel which comprises equal numbers of male and female barristers, but where the significant majority of the work is allocated to men, and where their chances of future promotion through the ranks appear statistically considerably lower than those of their male counterparts.

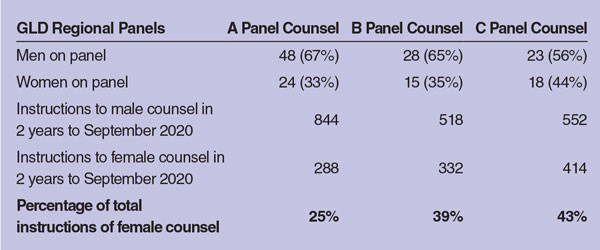

The Regional Panel moved from a single Panel to the current three Panels in 2018. The figures for 2020 are:

I asked both the Welsh government and GLD how they ensure that work is fairly allocated to barristers on the QC, A, B and C Panels.

The Welsh government told me that there was detailed internal operating guidance on engagement of counsel. They said that there are internal monitoring arrangements, including regular monitoring of panel distribution and regular reporting to the Welsh Government Legal Services Management Board. Reports on panel usage and distribution of work are periodically submitted to the General Counsel for Wales.

GLD does not undertake any monitoring of the distribution of work between QCs or between panel counsel. GLD referred me to an internal policy that governs the instruction of QCs, in which the allocating lawyer must have regard to ‘encouraging diversity’. However, they did not point to any policy or guidance in relation to the instruction of A, B and C Panel members. I was told that panel appointments are made ‘in accordance with equal opportunities, discrimination law and best practice’. Efforts are made to encourage applications from as wide a pool as possible and approaches are made to diversity groups including the Association of Women Barristers. Selection boards are comprised of men and women in equal numbers.

GLD stated that it works hard to ensure that instructions are fairly allocated to those on each panel, although in the absence of any central record-keeping or any monitoring of work allocation, it is unclear how it is endeavouring to do this. I was told that all staff are trained in unconscious bias and that there are regular meetings with clerks to discuss the volume and types of work that their panel members are receiving; in these meetings GLD representatives ask specifically about equality and diversity issues. I am told that feedback ‘is always positive’ and that ‘we have never had complaints about the quality of work received by females as opposed to men’.

With respect to GLD, these comments appear to be slightly naïve. First, they may not reflect an understanding of the reluctance of female barristers – particularly junior barristers – to raise concerns with their (largely male) clerks or elsewhere within chambers. Second, GLD is likely to be an important source of work for the chambers in question, and barristers and clerks will be wary of raising issues with such a client in case it has a detrimental impact on the number of instructions coming into chambers. Finally, no single chambers can know how GLD allocates its work more widely and so will not know, for example, how much GLD work (and at what level) is being allocated to female panel members at other chambers – something that the GLD itself does not apparently monitor or record.

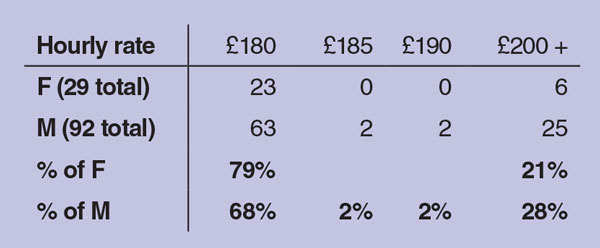

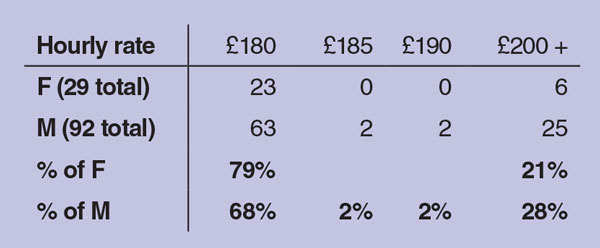

GLD pays barristers on the A, B and C Panels, and on the Regional Panels the same hourly rates. However, it pays barristers on the QC Panel different hourly rates. I was told that the higher rates are paid to silks appointed pre-2010 or where the nature of the expertise for a particular case commanded a higher hourly rate. I was not given any more information about the ‘nature of the expertise’ that might command higher hourly rates, or how this is objectively assessed by GLD.

I was given data relating to the 29 female QCs and 92 male QCs instructed between 1 July 2018 and 30 June 2020 which showed:

The above data shows that female QCs were significantly more likely to be instructed at the lowest hourly rate of £180 per hour than their male counterparts (79% as against 68%). The highest hourly rate (£275) was paid to a male QC.

I asked the Welsh government and GLD how they were complying with their public sector equality duties when exercising their public function of instructing barristers to advise and represent the UK and Welsh governments. The Welsh government referred me to its internal operating guidance, and the role of senior management oversight in decisions about instructing barristers. GLD did not address this question in its response to me.

The figures speak for themselves. Across all types of publicly funded work there are significant gender disparities in access to work and in remuneration. If the current situation maintains, over the course of their careers the young male barristers of the Bar school class of 2020 will have better access to quality work, will claim more of the available pot and will have a greater likelihood of taking silk than their female counterparts, whatever the jurisdiction, excepting those litigating under the Children Act. It is difficult to see how the profession will ever achieve equal numbers of men and women in silk, or on the High Court bench, if these disparities are not addressed.

Since 2017 a variety of studies have uncovered empirical evidence pointing to endemic and entrenched gender inequality. While some government departments – notably the CPS – have taken note and are consequently taking active steps to advance equality of opportunity between male and female barristers pursuant to their public sector equality duty, other departments appear to be less vigilant and less proactive. Monitoring and transparency are key.

As a result of my correspondence with GLD around this article, it is now fully alive to the problem. Simon Harker, of GLD Knowledge & Innovation, said: ‘GLD [Heads of Group] have found this report and the correspondence around its production extremely useful in highlighting issues around gender and fair access to government civil work. They take equality of opportunity extremely seriously. They say that, as a result of this report, they will be giving the issue of fair access greater prominence in the selection of counsel.’

For the self-employed Bar, the role of individual sets is crucial; tenant barristers might ask their chambers’ management committees whether the gender pay gap is monitored within chambers, and if it is not, why it is not.

Help is on hand from the Bar Council: Dee Masters is leading a Bar Council Retention Committee initiative to produce a guide for the Bar, encouraging chambers to monitor their pay gap. She sent me an advance copy of the guide, called the Work Distribution by Sex Monitoring Toolkit 2020. It contains detailed guidance for individual chambers on how to monitor the pay gap effectively; it is likely to be an invaluable resource for chambers and the profession as a whole moving forward.

Are the disparities in the allocation of publicly funded work described in this article simply an unfortunate hangover from history? Can they be explained as the result of ‘lifestyle choices’? To what extent does unconscious bias – expectation of what a proper brief should look like – affect client choice? How do government lawyers and managers apply their diversity training to their allocation of work externally, and how is that monitored? How does the traditional chambers model, historically so dependent on patronage, work in a modern meritocracy? What role might the structure and composition of the clerks’ room have to play? The answers to these questions are likely to be multi-faceted, complex and may require independent evaluation. Perhaps it is now time for the Solicitors’ Regulatory Authority and the Equality and Human Rights Commission to investigate.

*

| Male | Female | |

| QC | 13 | 2 |

| A Panel | 8 | 2 |

| B Panel | 5 | 4 |

| C Panel | 2 | 1 |

| Others (possibly JJ scheme) | 2 | 0 |

Women at the Bar have for some years expressed concerns surrounding equality of remuneration and opportunity. Although there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of gender discrimination – conscious and unconscious – efforts to assess and address the perceived inequalities have been hampered by lack of direct evidence to either support or undermine the validity of the concerns.

This began to change in July 2017 when Public Law published ‘Patronising Lawyers? Homophily and Same-Sex Litigation Teams before the UK Supreme Court’, an academic paper which examined the gender of advocates appearing in the Supreme Court. Its methodology and evidenced conclusions suggested significant gender disparity in instruction, largely resulting from sponsorship of junior male barristers by senior male barristers. This prompted the Bar Council’s Equality, Diversity and Social Mobility (EDSM) Committee to commission a study into gender and fair access, which as a committee member at the time, I led. The resultant 2018 report was subsequently published in Counsel magazine across two issues. I was asked to revisit the subject in 2019 for Counsel’s edition commemorating 100 years of women at the Bar.

I was able to analyse the earnings by gender at the criminal Bar with the assistance of detailed records held and shared by the Legal Aid Agency (LAA) and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS); earnings in the family and civil jurisdictions remained largely opaque. In 2019, The Lawyer magazine produced some empirical evidence through its litigation tracker of commercial Bar data, revealing that the most active commercial litigation firms instructed a total of 810 barristers of whom only 19% were women. It also provided some evidence of significant disparity in instruction and remuneration within the Employment Appeals Tribunal.

Since then, in August 2020 The Lawyer investigated the instruction patterns of the top 50 disputes firms by revenue over the period July 2019-2020. That study found that Kirkland & Ellis, Travers Smith and Dentons instructed no female barristers on cases that reached judgment in that period. A further 20 firms in the top 50 allocated less than 20% of instructions to female barristers; the top 50 firm that instructed female barristers most frequently on cases that reached judgment was DAC Beachcroft, sending 27% of its instructions to women. Evidence of gender disparity in specific practice areas was beginning to mount. However, without comprehensive income data and analysis across all practice areas, the scale of the problem profession-wide could not be fully assessed. If the extent of the problem is unknown, it is difficult to address.

Towards the end of 2020 and for the first time, the Bar Standards Board (BSB) and the Bar Council each published empirical evidence of the gap in earnings by gender across the profession, with the BSB also publishing information about the ethnicity gap.

Every barrister must apply annually for practice certificate renewal, and in their application must specify their areas of practice in percentage terms, and their income for the previous year (within income brackets). In November 2020 the BSB published Income at the Bar by Gender and Ethnicity. This report, through analysis of barristers’ declared gross income in 2018, disclosed obvious inequalities. According to the BSB, in 2018 35% of the female Bar had a gross income of £60,000 or less, compared to 22% of the male Bar. 38% of male barristers grossed more than £150,000 compared to 18% of female barristers. While women now comprise 38% of the Bar as a whole, they make up 46% of barristers under 15 years’ call and 33% of barristers above 15 years’ call. The BSB found that 38% of female barristers under 15 years’ call had a gross income of less than £60,000; 26% of male barristers under 15 years’ call were in that income bracket. At the higher end, 13% of female barristers under 15 years’ call declared a gross income of more than £150,000, compared to 28% of male barristers.

Looking at those in silk, the BSB found little observable pattern for those earning under £90,000. However, in the higher income brackets there were notable differences: 66% of female QCs earned between £90,000 and £500,000, compared to 48% of male QCs. In contrast, 34% of male QCs had an income of more than £500,000 compared to 25% of female QCs.

In the same week the BSB issued its report based on 2018 figures, the Bar Council released a Table of Earnings by Gender reflecting the 2019 practice certificate declarations. It reveals continuing inequality at the Bar across all areas of legal practice, which it breaks down into 30 separate practice areas. For the first time, empirical evidence is available in respect of the whole profession.

In addition to its published table, the Bar Council has shared with chambers further unpublished extrapolations of its data showing the average difference in 2019 earnings between men and women in different practice areas. As the bar chart below shows, defamation was the only practice area in which there was parity, with women conducting 28% of the work and receiving 28% of the income.

There was one practice area out of the 30 defined by the Bar Council in which women earned on average more than men: in ‘family (children)’ they earned 6% more than their male counterparts. However, in ‘family (other)’ they earned 46% less than men.

The figures come with caveats: the Bar Council states that neither its Table nor the extrapolations set out above, ‘reflect seniority or working patterns so can’t be interpreted as showing that women and men in comparable situations are necessarily being paid differently…[however] these figures demonstrate that we are a long way off equality at the Bar’.

However, in relation to the criminal Bar, Rose Holmes, Research Manager at the Bar Council told me: ‘The Bar Council’s forthcoming joint analysis with the Ministry of Justice of the fee income of publicly funded criminal barristers 2015-2019 (currently confidential under a data-sharing agreement) but to be published soon, confirms a systemic pattern of women barristers earning less than their male counterparts, even when seniority and case volume are taken into account. This disparity is amplified when race and gender are considered together, with Black women earning less than any other group at the criminal Bar.’

The 2020 Chair of the Bar Council, Amanda Pinto QC has described the discrepancies in pay between male and female barristers as ‘shocking’ and has called for the Bar to ‘confront, not hide, this profession-wide problem’.

In light of the Bar Council and BSB figures, and ahead of the forthcoming Bar Council and Ministry of Justice joint analysis of publicly funded criminal fee income by gender and ethnicity, I returned to the CPS and LAA who were again kind enough to provide their data for publicly funded work for the year ending March 2019. There is comparatively little private work in crime, so these figures give good insight into access to work across the jurisdiction. This will be the last year in which figures are unaffected by the pandemic. Anyone hoping for an improvement on previous years will be disappointed.

These figures mirror very closely those of last year; if anything, they are very slightly down.

Like the defence figures, CPS payments are down on last year, when there were 102 women in top 500 fee-earners from CPS, 19 women in top 100 and 37 in top 200.

I spoke to Michael Hoare, a senior court business adviser at the CPS who is working with the Bar Council and Women in Criminal Law (WICL) to address the problem of gender inequality. He told me that internally the CPS has strong equality policies and that women comprise 37% of the 248 crown advocates employed by the CPS nationwide – broadly in line with the proportion of women practising at the Bar. Further, across all CPS lawyer grades, the percentage of female employees increases to 62%. Just over a third of CPS lawyers are barristers.

My 2019 report concluded: ‘The CPS operates an equal opportunities policy in-house; will it now also require gender-diverse lists from chambers at all prosecuting grades? Whether or not the criminal Bar as an entity is prepared to tolerate inequity, its main paymaster is unlikely to for much longer.’ I was unaware at the time, but partly as a result of the 2018 EDSM report published in Counsel, the CPS was already taking a close look at how it was ensuring gender equality when instructing advocates externally. Throughout 2020 a steering-group chaired by CPS CEO Rebecca Lawrence with representatives from the CBA and the Bar Council, undertook a review of CPS data which reveals:

Mr Hoare described the gender discrepancy in these areas, in the context of the available pool, as ‘significant’; he emphasised the importance of looking beyond the data – eg that 85% of all fees in respect of high value frauds were paid to men, notwithstanding that 24% of level 3 and 4 counsel on the CPS Specialist Fraud Panel are female – and engaging with the Bar better to understand the reasons why.

Based on the data, the CPS is taking forward a number of actions, which Rebecca Lawrence has set out in a recent blog for Bar Talk (25 November 2020), and which include the following:

Progress against these actions will be monitored by the CPS-Bar Steering Group. The above data gives a national picture; Mr Hoare told me that there are differences between Circuits. For example, on the Northern Circuit there are only three female silks practising crime and only one of those prosecutes regularly. The absence of a diverse cadre of advocates available for CPS work on some Circuits is a topic of discussion with Circuit leaders and has led in some circumstances to the CPS instructing off-Circuit in order to achieve diversity. The CPS will soon publish its new five-year advocacy strategy, covering both in-house and external advocacy, which will place particular emphasis on diversity and inclusion.

Katy Thorne QC, Founder and Chair of WICL commented, ‘These [2018-19] figures confirm WICL’s own research on equal pay gathered from a number of chambers. Sadly, women just don’t get a fair crack at the whip. That’s why we were really pleased to sit down with the CPS and challenge them on their own briefing figures. We are delighted they are now working with us to improve. It proves that without clear statistics and data even the most progressive of organisations will unknowingly perpetuate the existing inequalities in briefing. It’s vital that everyone from chambers to instructing solicitors to the LAA do their own number crunching and ensure that briefing practices are not gender skewed and that barristers in the criminal courts from top to bottom reflect society as a whole.’

Mr Hoare also raised the need for chambers management committees to be alive to – and address – the issue within individual sets. I asked him if he had any thoughts on the effect that the historical lack of diversity in clerks’ rooms may be having. He told me that currently only three of the 48 London chambers doing criminal work has a female senior clerk. He points to a specific issue surrounding late returns, stating that the focus is on getting the work covered at short notice, sometimes at the expense of ensuring the fair allocation of cases across all protected characteristics. Moving forwards, the CPS will be re-emphasising the importance of this – to both chambers and their own staff – and monitoring the protected characteristics of those it instructs, and accepts on return, much more closely to ensure that it achieves greater diversity.

So, the CPS is now alive to the issue and is taking positive action. What of other government departments? Gender diversity, or the lack thereof, in government instructions was brought into stark and public focus during the Article 50 litigation. An outsider looking at live video footage of the all-male counsel teams instructed by the UK government, the Welsh government and the Attorney General for Northern Ireland to present the Supreme Court arguments in the most high profile and constitutionally important legal action of the century to date might reasonably have inferred that the Bar was as male dominated in 2019 as it was in 1919.

I asked the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) why the UK government has only instructed men in the Brexit-related constitutional litigation to date (by which I meant the Article 50 litigation and the Prorogation case). The AGO responded: ‘Both men and women were initially considered, but because of issues of suitability and availability, the counsel team ended up being wholly male. However, GLD and the AG certainly recognise the benefit to female counsel in appearing in high profile cases and realise that given the breadth of talent among female members of the panel and is silk it is only natural that they should be instructed in such cases. We expect this to happen more frequently in the future. For example, two female A panellists have recently been conducting our important C-19 cases.’ I would venture to suggest that the obvious benefit of female counsel appearing in high-profile cases extends beyond the particular counsel concerned and is vital for democracy and wider society. Anyone doubting that proposition only need look at the sea change in the focus of House of Lords and then Supreme Court decisions – and in the consequent development of the law – over the 25 years that our final court of appeal had the benefit of Lady Hale.

I asked a number of questions surrounding gender diversity of the AGO, the Government Legal Department (GLD) and the Counsel General to the Welsh Government, and I am grateful to each organisation for agreeing to provide me with the gender information I sought without my having to make a formal request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. GLD administers the Panel Counsel system on behalf of the Attorney General, and so Simon Harker of GLD responded on behalf of both GLD and the Attorney General.

I asked both the Welsh government and GLD how many men and women had been appointed to their panels of counsel.

The Welsh government does not have a C Panel of counsel; however, unlike the Attorney General it does operate an appointments process for its panel of QCs. The figures are broken down in the table below:

Only 25% of barristers appointed to Welsh government counsel panels, and therefore able to accept government instructions, are female. It is particularly surprising to see female barristers so poorly represented in the panels of junior counsel.

On behalf of the GLD and Attorney General’s Office, Mr Harker told me: ‘Successive Law Officers have been keen to advance equality of opportunity between men and women at the Bar and the panels have been seen as a way of achieving this.’

The GLD runs London and Regional Panels for EU and civil work carried out on behalf of the UK government. There has never been a female Treasury Devil (or female First Treasury Counsel). The GLD says: ‘There is no reason why Sir James’ successor should not be female. The appointment process will be in accordance with equal opportunities, the law and best practice.’ The next appointment will almost certainly come from the Attorney General’s QC Panel. I was not provided with data surrounding the QC Panel’s composition on the basis that this ‘is simply a list of QCs who have acted for the Government in the past or have indicated… a willingness to act for the Government in the future. There is no selection process. A QC just asks to have his or her name added.’

However, I was given detailed data for the current London A, B and C Panels, and also for the A, B and C Panels in 2014. The position for the A Panel is now significantly worse than it was in 2014, the position for the B Panel has improved, and the position for the C Panel has not changed. It is unclear why the female C Panellists of 2014 do not seem to have become the A and B Panellists of 2020.

London Panel figures:

I was also provided with detailed data regarding the gender breakdown on the Regional A, B and C Panels. The position is similar to that of the national panels and is set out in the table in the section below.

I asked both the Welsh government and GLD how many times men and women had been instructed in the last 24 months, in which courts (from the European Court of Justice down to other courts and tribunals) and in what capacity (leader, sole counsel, led junior, etc).

The Welsh government was able to provide me with detailed data on this, which is set out below. The data showed that although women are poorly represented on all panels, those on the A and B Panels actually received per capita more instructions than the men, while the male QCs were allocated more work proportionately than the female silks.

Disappointingly GLD was unable to provide me with equivalent data for the male and female barristers they instruct, although some of this information must be a matter of public record available on platforms such as BAILII. I was told that GLD does ‘not keep central records which go down to the level of detail of who has been instructed in which type of court or who has been led or not’. I was not told why it does not keep such records.

However, GLD was able to provide me with data about the number of men and women who have invoiced them over 24 month periods (24 months to June 2020 for QCs and 1 September to 31 August for A, B and C Panels) and the number of instructions in relations to which they invoiced. The GLD records instructions as cases invoiced per quarter. If a barrister invoices on a single case four times in one quarter that is recorded as one ‘instruction’. If she invoices on that same case once per quarter over a year, that is recorded as four ‘instructions’. Accordingly, ‘instructions’ are not individual cases, nor are they individual invoices but rather a hybrid of the two. That data showed the following:

It is particularly striking that on the C Panel where female barristers comprise 48% of barristers on the Panel, 72% of GLD’s ‘instructions’ went to male barristers. Most C Panel members are under 10 years’ call, typically appointed in their mid to late twenties. It seems unlikely that the significant disparity in work allocation at this most junior level should all be attributable to lifestyle decisions, or maternity leave. At the more senior level, not only has the A Panel increased by seven men to every woman since 2014, the 30% of A panellists who are female received only 22% of the ‘instructions.’ While both GLD and the Welsh government said that they were keen to encourage more women to join their panels, female counsel might be reluctant to join a panel which comprises equal numbers of male and female barristers, but where the significant majority of the work is allocated to men, and where their chances of future promotion through the ranks appear statistically considerably lower than those of their male counterparts.

The Regional Panel moved from a single Panel to the current three Panels in 2018. The figures for 2020 are:

I asked both the Welsh government and GLD how they ensure that work is fairly allocated to barristers on the QC, A, B and C Panels.

The Welsh government told me that there was detailed internal operating guidance on engagement of counsel. They said that there are internal monitoring arrangements, including regular monitoring of panel distribution and regular reporting to the Welsh Government Legal Services Management Board. Reports on panel usage and distribution of work are periodically submitted to the General Counsel for Wales.

GLD does not undertake any monitoring of the distribution of work between QCs or between panel counsel. GLD referred me to an internal policy that governs the instruction of QCs, in which the allocating lawyer must have regard to ‘encouraging diversity’. However, they did not point to any policy or guidance in relation to the instruction of A, B and C Panel members. I was told that panel appointments are made ‘in accordance with equal opportunities, discrimination law and best practice’. Efforts are made to encourage applications from as wide a pool as possible and approaches are made to diversity groups including the Association of Women Barristers. Selection boards are comprised of men and women in equal numbers.

GLD stated that it works hard to ensure that instructions are fairly allocated to those on each panel, although in the absence of any central record-keeping or any monitoring of work allocation, it is unclear how it is endeavouring to do this. I was told that all staff are trained in unconscious bias and that there are regular meetings with clerks to discuss the volume and types of work that their panel members are receiving; in these meetings GLD representatives ask specifically about equality and diversity issues. I am told that feedback ‘is always positive’ and that ‘we have never had complaints about the quality of work received by females as opposed to men’.

With respect to GLD, these comments appear to be slightly naïve. First, they may not reflect an understanding of the reluctance of female barristers – particularly junior barristers – to raise concerns with their (largely male) clerks or elsewhere within chambers. Second, GLD is likely to be an important source of work for the chambers in question, and barristers and clerks will be wary of raising issues with such a client in case it has a detrimental impact on the number of instructions coming into chambers. Finally, no single chambers can know how GLD allocates its work more widely and so will not know, for example, how much GLD work (and at what level) is being allocated to female panel members at other chambers – something that the GLD itself does not apparently monitor or record.

GLD pays barristers on the A, B and C Panels, and on the Regional Panels the same hourly rates. However, it pays barristers on the QC Panel different hourly rates. I was told that the higher rates are paid to silks appointed pre-2010 or where the nature of the expertise for a particular case commanded a higher hourly rate. I was not given any more information about the ‘nature of the expertise’ that might command higher hourly rates, or how this is objectively assessed by GLD.

I was given data relating to the 29 female QCs and 92 male QCs instructed between 1 July 2018 and 30 June 2020 which showed:

The above data shows that female QCs were significantly more likely to be instructed at the lowest hourly rate of £180 per hour than their male counterparts (79% as against 68%). The highest hourly rate (£275) was paid to a male QC.

I asked the Welsh government and GLD how they were complying with their public sector equality duties when exercising their public function of instructing barristers to advise and represent the UK and Welsh governments. The Welsh government referred me to its internal operating guidance, and the role of senior management oversight in decisions about instructing barristers. GLD did not address this question in its response to me.

The figures speak for themselves. Across all types of publicly funded work there are significant gender disparities in access to work and in remuneration. If the current situation maintains, over the course of their careers the young male barristers of the Bar school class of 2020 will have better access to quality work, will claim more of the available pot and will have a greater likelihood of taking silk than their female counterparts, whatever the jurisdiction, excepting those litigating under the Children Act. It is difficult to see how the profession will ever achieve equal numbers of men and women in silk, or on the High Court bench, if these disparities are not addressed.

Since 2017 a variety of studies have uncovered empirical evidence pointing to endemic and entrenched gender inequality. While some government departments – notably the CPS – have taken note and are consequently taking active steps to advance equality of opportunity between male and female barristers pursuant to their public sector equality duty, other departments appear to be less vigilant and less proactive. Monitoring and transparency are key.

As a result of my correspondence with GLD around this article, it is now fully alive to the problem. Simon Harker, of GLD Knowledge & Innovation, said: ‘GLD [Heads of Group] have found this report and the correspondence around its production extremely useful in highlighting issues around gender and fair access to government civil work. They take equality of opportunity extremely seriously. They say that, as a result of this report, they will be giving the issue of fair access greater prominence in the selection of counsel.’

For the self-employed Bar, the role of individual sets is crucial; tenant barristers might ask their chambers’ management committees whether the gender pay gap is monitored within chambers, and if it is not, why it is not.

Help is on hand from the Bar Council: Dee Masters is leading a Bar Council Retention Committee initiative to produce a guide for the Bar, encouraging chambers to monitor their pay gap. She sent me an advance copy of the guide, called the Work Distribution by Sex Monitoring Toolkit 2020. It contains detailed guidance for individual chambers on how to monitor the pay gap effectively; it is likely to be an invaluable resource for chambers and the profession as a whole moving forward.

Are the disparities in the allocation of publicly funded work described in this article simply an unfortunate hangover from history? Can they be explained as the result of ‘lifestyle choices’? To what extent does unconscious bias – expectation of what a proper brief should look like – affect client choice? How do government lawyers and managers apply their diversity training to their allocation of work externally, and how is that monitored? How does the traditional chambers model, historically so dependent on patronage, work in a modern meritocracy? What role might the structure and composition of the clerks’ room have to play? The answers to these questions are likely to be multi-faceted, complex and may require independent evaluation. Perhaps it is now time for the Solicitors’ Regulatory Authority and the Equality and Human Rights Commission to investigate.

*

| Male | Female | |

| QC | 13 | 2 |

| A Panel | 8 | 2 |

| B Panel | 5 | 4 |

| C Panel | 2 | 1 |

| Others (possibly JJ scheme) | 2 | 0 |

HHJ Nott continues her ground-breaking series with an analysis of 2019/20 publicly funded criminal/civil instructions and newly released profession-wide data, as the Bar is called upon to ‘confront, not hide’ the shocking discrepancies in pay and access to work between male and female barristers

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar