*/

As I write these words,* President Biden is warning the world that a Russian invasion of Ukraine is imminent. The Russian media is falsely reporting alleged human rights abuses on a mass scale by Ukrainians against ethnic Russians. Donbas separatists are making baseless accusations that the Ukrainian army has shelled civilian areas. We may be witnessing a ‘false flag’ disinformation campaign as the pretext for war.

Russia’s periodically tenuous relationship with truth was examined in detail by Peter Pomerantsev in his recent book This is Not Propaganda (Faber, 2019). The lack of respect for objective facts has not stopped at the courtroom door. In December 2021 the Russian Supreme Court issued an order ‘liquidating’ (its word) Memorial, the human rights group established more than 30 years ago to investigate and document Soviet repression and its innumerable victims. ‘Memorial creates a false image of the Soviet Union as a terrorist state…Why should we, the descendants of the victors, watch attempts to rehabilitate traitors to the motherland and Nazi collaborators? Perhaps because someone is paying them for it,’ submitted the state prosecutor. ‘It makes us repent of the Soviet past, instead of remembering its glorious history.’ The ostensible reason for Memorial’s suppression was that it did not properly identify itself as a ‘foreign agent.’ In today’s Russia if an organisation receives money from abroad it must self-designate itself on all its publications.

Police officers detain a demonstrator as people gather in front of Russia’s Supreme Court to protest as it ruled that one of the country’s oldest and most prominent human rights organisations, Memorial, should be shut down: 28 December 2021.

Meanwhile, campaigner and politician Alexei Navalny is currently being prosecuted for supposed embezzlement of donations to his own anti-corruption organisation.** His trial is taking place in the penal colony where he is already incarcerated. Amnesty International has described the hearing as a ‘sham trial, attended by prison guards rather than the media’.

Courtrooms have been used as vehicles for disinformation and legitimisation of oppression for centuries. Decisions by judges or juries are accorded enhanced status because apparently issuing from a court of justice. Repressive regimes often prefer to use compliant courts as the means to eradicate enemies rather than resorting to simple extra-judicial detention or killing. ‘Look’ they can say, ‘a court has decreed it so. The charge must have been well-founded.’ We see revenge and political expediency being clothed with some form of judicial legitimacy in the trials of the Regicides in England in 1660, supposed counter-revolutionaries in the Paris Revolutionary Tribunal of 1793, and the July 1944 conspirators in the People’s Court in Berlin.

The fictionalisation of the courtroom – by this I mean the conversion of the court into a perverter rather than promoter of truth – reached its apogee in the last of the so-called Moscow ‘show trials’. In March 1938, in the pre-revolutionary grandeur of the Hall of Columns, 21 defendants sat in a makeshift dock, many of them Bolsheviks who had been instrumental in the events of 20 years earlier and the creation of the Soviet state. They were now accused of the most monstrous crimes: plotting the murder of Stalin and Lenin; conspiring to wreck the Soviet economy; conniving with foreign powers to attack their own country. The principal defendant was Nikolai Bukharin, one of the leading theorists of Bolshevism.

The prosecutor, Andrey Vyshinsky, a veteran of political trials, had perfected his denunciations into a language of elaborate fury. ‘Our people are demanding one thing: the traitors and spies who are selling our country to the enemy must be shot like dirty dogs. Our people are demanding one thing: crush the accursed reptile….’

Andrey Vyshinsky

Twenty of the 21 defendants pleaded guilty. During the trial they did not confine themselves to formal admissions of culpability. Instead, they participated in an orgy of self-abasement, each seeking to outdo the other in self- and mutual-denunciation: ‘The monstrousness of my crimes is immeasurable… I don’t consider it possible to plead for clemency… I depart as a traitor to my Party, as a traitor who should be shot.’ For hour upon hour the accused provided elaborate narratives of their apparent crimes: illicit meetings with Trotsky to conspire to overthrow the Soviet state; murder plots; poisonings; wrecking operations.

Yet almost everything the defendants said throughout the several days of the trial was untrue. They knew it. The prosecutor knew it. The judges knew it. Everyone was acting a part in a grand theatrical production where the outcome and sentences were pre-determined. The judges had already pre-arranged them with the prosecutor and Stalin.

This was clearly no ordinary trial. It was a grotesque parody, a display carefully orchestrated after months of planning. Everyone was playing their part in this grand ceremonial of Stalin’s Great Terror. And everyone in the courtroom, not just the accused, was frightened. The prosecutor and the judges knew that if they did not deliver a seamless production to the world, ending in the accused fully confessing their crimes and willingly embracing their fate, then they would be deemed to have failed. One of the judges who had condemned Marshal Tukhachevksy to death the year before had been heard to say, ‘Tomorrow I’ll be put in the same place.’ And he was right: most of the tribunal were subsequently shot.

Historians and psychologists have been fascinated by the thought processes that underlay the defendants’ seemingly enthusiastic participation in their own destruction. Day after day, in answers to questions put to them by the prosecutor, the defendants piled lie upon lie in their own incrimination and did so with gusto.

One of their principal motivations was the promise that the more they played along with the fictional production, and acted their part in it, the more likely it was that Stalin would save them from the gallows. And it was not only their own lives which were at stake. Many of the defendants (all of them male) had wives and children. Although it is now impossible to know precisely what accommodations were arrived at, it is thought that each was warned that failure to cooperate would lead to the murder of family members.

Lev Kamenev had been a principal defendant in the first of the show trials in 1936. Stalin had personally promised him that he would be spared if he confessed his supposed crimes. On the very night of his conviction, having played his part to a tee, he was nonetheless shot. In the ensuing years, his wife, and both his sons, were also executed.

The Moscow show trials of 1936 to 1938 were both monstrous and fascinating. Stalin did not require judicial process to provide a platform for the liquidation of his supposed enemies. The vast majority of the victims of the Great Terror were shot without any form of legal procedure. But he had a wider purpose in organising these trials than the simple eradication of supposed opponents. They were held in public and attended by foreign journalists and diplomats. They continued over many days and were even filmed. You can listen to Vyshinsky’s tirades on YouTube. The proceedings were covered around the world.

Holding show trials of this sort necessarily involved an element of risk. After all, what if the defendants seized the opportunity to turn the tables on the prosecution, and publicly denounced the charges for what they were – pure fantasy? What if they gave evidence of the torture they had endured to extract their confessions, and the gruesome threats levelled against them? What if the observers, both domestic and foreign, saw through the fictionality of it all?

Reading the transcripts of the trials now, and of course bearing in mind all we know of Stalin’s atrocities, it seems astonishing that anyone was taken in. Some of the charges were absurd. One of the defendants was accused of contaminating butter with nails and powdered glass; another of the destruction of 50 truck-loads of eggs. Senior Kremlin doctors were accused of poisoning the writer Maxim Gorky.

Yet the trials were stage-managed with consummate skill. Vyshkinsky’s displays of righteous indignation seemed to be borne of genuine rather than confected outrage. The judges maintained the right degree of dignity. The defendants had rehearsed their parts to ensure that they brought a sufficient degree of verisimilitude to their newly-cast roles of murderers and traitors.

There were those around the world who were scornful of such nonsense. But many were not. The United States Ambassador to the USSR swallowed it whole. Denis Pritt, an English silk and Labour MP, attended the first so-called Zinoviev/Kamenev show trial in 1936. He wrote: ‘We can feel confident that when the smoke has rolled away from the battlefield of controversy it will be realised that the charges were true, the confessions correct, and the prosecution fairly conducted.’

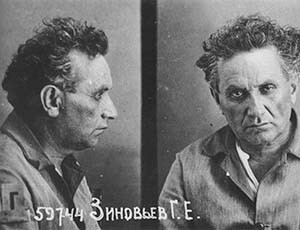

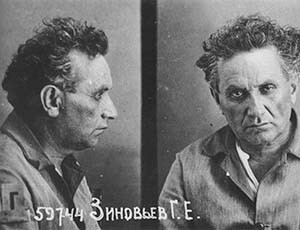

Police photographs of Grigory Zinoviev, a defendant in the first Moscow show trial, taken by the NKVD after his arrest in 1934.

Stalin had multiple purposes for the Moscow trials. At an elementary level, the fate of the defendants, in almost all cases instant execution, was designed to cow potential dissidents into silent submission. The trials were also exercises in calculated humiliation. The sight of these wretched men being ground into the dust must have sapped the morale of even the hardiest of oppositionist. And it was made sure that the defendants, previously men of the highest rank in the Soviet Union, came before the court looking broken and crushed. The pathetic sight of the conspirators in the make-shift dock seemed only to enhance the might of the Soviet state.

But there were other messages being communicated by the Moscow trials. Stalin wanted to project to the Russian population the idea that there was a vast conspiracy against the state, and only he could withstand its depredations. A conspiracy of this sort justified the purge that took place principally in the extra-judicial arena. What better way to establish a narrative that the state was in danger and exceptional measures were required?

Stalin also needed scapegoats for the appalling mismanagement of the Russian economy, and the terrible suffering of the Russian people, that had occurred under his rule. Why, millions of people had no doubt asked, are we hungry? Why is there nothing to buy in the shops? Why does the butter taste awful? Now, through the formality of the trial, they had an answer. It was the fault, not of the government, but of shadowy conspirators intent on debilitating the state.

Vyshinsky has become a byword for legal viciousness and mendacity. Modern Russia may be some way removed from its Stalinist precursor, but in the state prosecutor’s words of condemnation of Memorial last year we can hear echoes of Vyshinsky’s own denunciations of non-existent traitors, and a continuation of the theme of foreign orchestrated treachery undermining the state. The courtroom is again being used to suppress and bend truth; to create what Pomersantsev describes as ‘ersatz reality’.

* 20 February 2022. The Russian invasion of Ukraine commenced on 24 February.

** Navalny was convicted and sentenced to a further nine years’ imprisonment on 22 March 2022. In its report on the same day, the New York Times alleged that during the trial ‘the judge had received multiple phone calls from a number that researchers traced to the head of public relations for the presidential administration’.

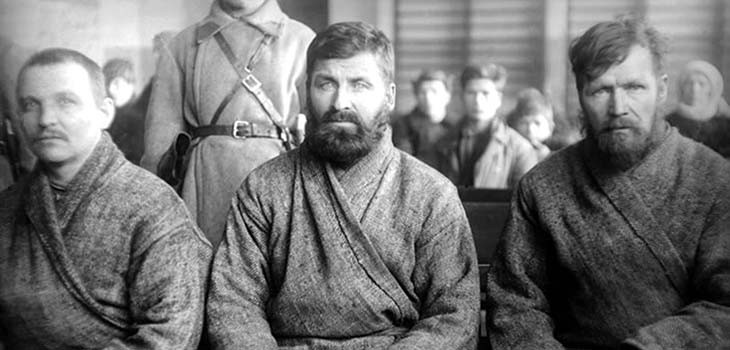

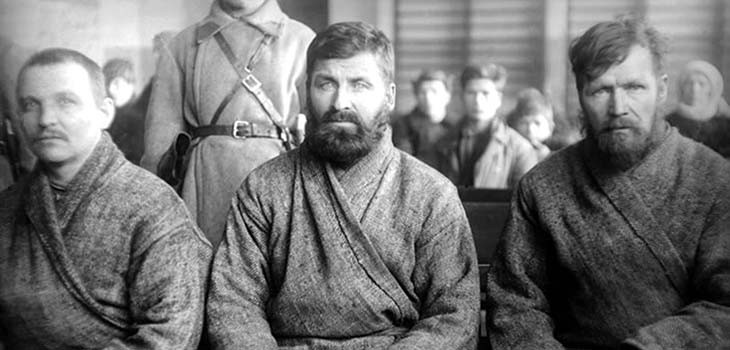

Pictured top: Defendants in one of the show trials held in the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938.

As I write these words,* President Biden is warning the world that a Russian invasion of Ukraine is imminent. The Russian media is falsely reporting alleged human rights abuses on a mass scale by Ukrainians against ethnic Russians. Donbas separatists are making baseless accusations that the Ukrainian army has shelled civilian areas. We may be witnessing a ‘false flag’ disinformation campaign as the pretext for war.

Russia’s periodically tenuous relationship with truth was examined in detail by Peter Pomerantsev in his recent book This is Not Propaganda (Faber, 2019). The lack of respect for objective facts has not stopped at the courtroom door. In December 2021 the Russian Supreme Court issued an order ‘liquidating’ (its word) Memorial, the human rights group established more than 30 years ago to investigate and document Soviet repression and its innumerable victims. ‘Memorial creates a false image of the Soviet Union as a terrorist state…Why should we, the descendants of the victors, watch attempts to rehabilitate traitors to the motherland and Nazi collaborators? Perhaps because someone is paying them for it,’ submitted the state prosecutor. ‘It makes us repent of the Soviet past, instead of remembering its glorious history.’ The ostensible reason for Memorial’s suppression was that it did not properly identify itself as a ‘foreign agent.’ In today’s Russia if an organisation receives money from abroad it must self-designate itself on all its publications.

Police officers detain a demonstrator as people gather in front of Russia’s Supreme Court to protest as it ruled that one of the country’s oldest and most prominent human rights organisations, Memorial, should be shut down: 28 December 2021.

Meanwhile, campaigner and politician Alexei Navalny is currently being prosecuted for supposed embezzlement of donations to his own anti-corruption organisation.** His trial is taking place in the penal colony where he is already incarcerated. Amnesty International has described the hearing as a ‘sham trial, attended by prison guards rather than the media’.

Courtrooms have been used as vehicles for disinformation and legitimisation of oppression for centuries. Decisions by judges or juries are accorded enhanced status because apparently issuing from a court of justice. Repressive regimes often prefer to use compliant courts as the means to eradicate enemies rather than resorting to simple extra-judicial detention or killing. ‘Look’ they can say, ‘a court has decreed it so. The charge must have been well-founded.’ We see revenge and political expediency being clothed with some form of judicial legitimacy in the trials of the Regicides in England in 1660, supposed counter-revolutionaries in the Paris Revolutionary Tribunal of 1793, and the July 1944 conspirators in the People’s Court in Berlin.

The fictionalisation of the courtroom – by this I mean the conversion of the court into a perverter rather than promoter of truth – reached its apogee in the last of the so-called Moscow ‘show trials’. In March 1938, in the pre-revolutionary grandeur of the Hall of Columns, 21 defendants sat in a makeshift dock, many of them Bolsheviks who had been instrumental in the events of 20 years earlier and the creation of the Soviet state. They were now accused of the most monstrous crimes: plotting the murder of Stalin and Lenin; conspiring to wreck the Soviet economy; conniving with foreign powers to attack their own country. The principal defendant was Nikolai Bukharin, one of the leading theorists of Bolshevism.

The prosecutor, Andrey Vyshinsky, a veteran of political trials, had perfected his denunciations into a language of elaborate fury. ‘Our people are demanding one thing: the traitors and spies who are selling our country to the enemy must be shot like dirty dogs. Our people are demanding one thing: crush the accursed reptile….’

Andrey Vyshinsky

Twenty of the 21 defendants pleaded guilty. During the trial they did not confine themselves to formal admissions of culpability. Instead, they participated in an orgy of self-abasement, each seeking to outdo the other in self- and mutual-denunciation: ‘The monstrousness of my crimes is immeasurable… I don’t consider it possible to plead for clemency… I depart as a traitor to my Party, as a traitor who should be shot.’ For hour upon hour the accused provided elaborate narratives of their apparent crimes: illicit meetings with Trotsky to conspire to overthrow the Soviet state; murder plots; poisonings; wrecking operations.

Yet almost everything the defendants said throughout the several days of the trial was untrue. They knew it. The prosecutor knew it. The judges knew it. Everyone was acting a part in a grand theatrical production where the outcome and sentences were pre-determined. The judges had already pre-arranged them with the prosecutor and Stalin.

This was clearly no ordinary trial. It was a grotesque parody, a display carefully orchestrated after months of planning. Everyone was playing their part in this grand ceremonial of Stalin’s Great Terror. And everyone in the courtroom, not just the accused, was frightened. The prosecutor and the judges knew that if they did not deliver a seamless production to the world, ending in the accused fully confessing their crimes and willingly embracing their fate, then they would be deemed to have failed. One of the judges who had condemned Marshal Tukhachevksy to death the year before had been heard to say, ‘Tomorrow I’ll be put in the same place.’ And he was right: most of the tribunal were subsequently shot.

Historians and psychologists have been fascinated by the thought processes that underlay the defendants’ seemingly enthusiastic participation in their own destruction. Day after day, in answers to questions put to them by the prosecutor, the defendants piled lie upon lie in their own incrimination and did so with gusto.

One of their principal motivations was the promise that the more they played along with the fictional production, and acted their part in it, the more likely it was that Stalin would save them from the gallows. And it was not only their own lives which were at stake. Many of the defendants (all of them male) had wives and children. Although it is now impossible to know precisely what accommodations were arrived at, it is thought that each was warned that failure to cooperate would lead to the murder of family members.

Lev Kamenev had been a principal defendant in the first of the show trials in 1936. Stalin had personally promised him that he would be spared if he confessed his supposed crimes. On the very night of his conviction, having played his part to a tee, he was nonetheless shot. In the ensuing years, his wife, and both his sons, were also executed.

The Moscow show trials of 1936 to 1938 were both monstrous and fascinating. Stalin did not require judicial process to provide a platform for the liquidation of his supposed enemies. The vast majority of the victims of the Great Terror were shot without any form of legal procedure. But he had a wider purpose in organising these trials than the simple eradication of supposed opponents. They were held in public and attended by foreign journalists and diplomats. They continued over many days and were even filmed. You can listen to Vyshinsky’s tirades on YouTube. The proceedings were covered around the world.

Holding show trials of this sort necessarily involved an element of risk. After all, what if the defendants seized the opportunity to turn the tables on the prosecution, and publicly denounced the charges for what they were – pure fantasy? What if they gave evidence of the torture they had endured to extract their confessions, and the gruesome threats levelled against them? What if the observers, both domestic and foreign, saw through the fictionality of it all?

Reading the transcripts of the trials now, and of course bearing in mind all we know of Stalin’s atrocities, it seems astonishing that anyone was taken in. Some of the charges were absurd. One of the defendants was accused of contaminating butter with nails and powdered glass; another of the destruction of 50 truck-loads of eggs. Senior Kremlin doctors were accused of poisoning the writer Maxim Gorky.

Yet the trials were stage-managed with consummate skill. Vyshkinsky’s displays of righteous indignation seemed to be borne of genuine rather than confected outrage. The judges maintained the right degree of dignity. The defendants had rehearsed their parts to ensure that they brought a sufficient degree of verisimilitude to their newly-cast roles of murderers and traitors.

There were those around the world who were scornful of such nonsense. But many were not. The United States Ambassador to the USSR swallowed it whole. Denis Pritt, an English silk and Labour MP, attended the first so-called Zinoviev/Kamenev show trial in 1936. He wrote: ‘We can feel confident that when the smoke has rolled away from the battlefield of controversy it will be realised that the charges were true, the confessions correct, and the prosecution fairly conducted.’

Police photographs of Grigory Zinoviev, a defendant in the first Moscow show trial, taken by the NKVD after his arrest in 1934.

Stalin had multiple purposes for the Moscow trials. At an elementary level, the fate of the defendants, in almost all cases instant execution, was designed to cow potential dissidents into silent submission. The trials were also exercises in calculated humiliation. The sight of these wretched men being ground into the dust must have sapped the morale of even the hardiest of oppositionist. And it was made sure that the defendants, previously men of the highest rank in the Soviet Union, came before the court looking broken and crushed. The pathetic sight of the conspirators in the make-shift dock seemed only to enhance the might of the Soviet state.

But there were other messages being communicated by the Moscow trials. Stalin wanted to project to the Russian population the idea that there was a vast conspiracy against the state, and only he could withstand its depredations. A conspiracy of this sort justified the purge that took place principally in the extra-judicial arena. What better way to establish a narrative that the state was in danger and exceptional measures were required?

Stalin also needed scapegoats for the appalling mismanagement of the Russian economy, and the terrible suffering of the Russian people, that had occurred under his rule. Why, millions of people had no doubt asked, are we hungry? Why is there nothing to buy in the shops? Why does the butter taste awful? Now, through the formality of the trial, they had an answer. It was the fault, not of the government, but of shadowy conspirators intent on debilitating the state.

Vyshinsky has become a byword for legal viciousness and mendacity. Modern Russia may be some way removed from its Stalinist precursor, but in the state prosecutor’s words of condemnation of Memorial last year we can hear echoes of Vyshinsky’s own denunciations of non-existent traitors, and a continuation of the theme of foreign orchestrated treachery undermining the state. The courtroom is again being used to suppress and bend truth; to create what Pomersantsev describes as ‘ersatz reality’.

* 20 February 2022. The Russian invasion of Ukraine commenced on 24 February.

** Navalny was convicted and sentenced to a further nine years’ imprisonment on 22 March 2022. In its report on the same day, the New York Times alleged that during the trial ‘the judge had received multiple phone calls from a number that researchers traced to the head of public relations for the presidential administration’.

Pictured top: Defendants in one of the show trials held in the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar