*/

How will losing passporting rights affect the UK’s financial services sector? Saima Hanif argues that the equivalence regime is not a satisfactory alternative

As the President of the European Council Donald Tusk remarked, in response to comments from Boris Johnson that the UK could have its cake and eat it by keeping single market access without accepting free movement of persons: ‘There will be no cakes on the table, for anyone. There will be only salt and vinegar…’

As such, for the moment, the UK’s desired outcome seems unlikely to be achieved.

If access to the single market is not preserved, whilst London should continue to be a robust financial services centre, it will be weakened by the fragmentation of the services currently provided by UK financial institutions, as firms will have to maintain offices in both London and the EU. As a consequence, the regulatory burden and cost of doing business within the EU will increase.

Brexit options

Although the government has remained silent about what exactly Brexit will entail, it is safe to assume that the Swiss option and the Norwegian option will not be pursued, since both would require the UK to accept free movement of persons– and sovereignty over immigration is something that Theresa May’s government has explicitly prioritised as an outcome. At the same time, EU ministers have made clear on numerous occasions that the four freedoms are not separable: in the words of Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, ‘there can be no à la carte access to the single market’. If we take such proclamations at face value, then the UK will not be granted unrestricted access to the single market, with the result that financial services ‘passporting’ rights will not be preserved.

Passporting rights

The CRD IV (which contains the prudential rules for banks, building societies and investment firms) and MiFID (a directive which provides harmonised regulation for investment services) both contain a passporting regime, with the effect that an institution that is authorised and supervised by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)/Prudential Regulation Authority in London, is free to provide (or ‘passport’) those services into the EU, without needing to be separately regulated in each of the member states, or without having to establish a physical presence in that state. If a firm choses to have a physical presence, it can be in the form of a branch rather than a subsidiary, which does not need to be separately capitalised.

This has been a key attraction for non-EU institutions in particular, who have viewed London as a convenient gateway to the rest of Europe. Indeed, one of the specific requests in the memorandum published by the Japanese banks was ‘maintenance of the freedom of establishment and the provision of financial services, including the “single passport” system’. The memorandum noted that nearly half of all Japanese investment in the EU in 2015 went to the UK and the bulk of Japanese companies with an international presence have operations in the UK.

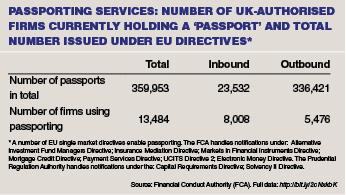

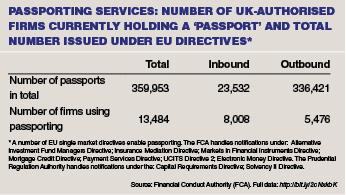

The FCA has also published data that shows that in respect of passporting, 5,476 UK firms hold one or more outbound passports to do business in the EU (see box). In short, the importance of passporting for the industry cannot be overstated.

If passporting rights are not preserved, UK firms providing services currently covered by the passport, will need to set up an authorised subsidiary within the EU and conduct EU business from that subsidiary. Depending on the expected volumes of trade, this could be a costly exercise as it could require the local presence of a sizeable workforce, and the establishment of appropriate systems and controls within the subsidiary. Correspondingly, EU banks that have branches in the UK may need to capitalise those separately for the first time; this is likely to be a huge cost for those institutions.

Equivalence

Once the UK has left the EU, it will become a third party country. The notion of ‘equivalence’ becomes relevant at this point. A number of EU directives contain provisions that enable firms in third party countries to provide services to the EU, without needing to be separately authorised by the EU regulator, as long as the regulatory ecosystem of that country is deemed to be ‘equivalent’ to that of the EU. Hence, at a superficial level, this appears to be a satisfactory alternative to the loss of passporting.

In truth, however, equivalence as it currently stands is a limited and piecemeal tool. The granting of equivalent status is principally a political decision, as it is the European Commission that has to issue a declaration of equivalence (albeit with input from technical agencies). The recognition of US clearing houses under EMIR, which took some three years to resolve, is an example of this. Moreover, the Commission can alter or withdraw a decision of equivalence at will, with little or no notice. In terms of ongoing equivalence, the UK would be tied to the EU regulatory framework, as it would have to ensure that any changes in the EU legislation were also reflected in the domestic legislation. Hence not only would the maintenance of an equivalence determination be uncertain, but politically, maintaining equivalence would, arguably, undermine the objective of leaving the EU in order to be ‘sovereign.’

It should also be noted that some directives do not contain any equivalence provisions at all (eg under the CRD IV, in respect of activities such as deposit-taking and lending there is no third country regime) – hence unless the equivalence regime were extended to cover these activities, there would be no alternative to the loss of passporting rights other than to establish a subsidiary within the EU. Even those directives that do contain equivalence provisions, are limited in their scope: whilst MiFID II/MiFIR has a specific third country regime (see Arts 46-49) the equivalence provisions only apply to the provision of investment services to per se professional clients and eligible counterparties: it does not cover retail investors or elective professional clients. Accordingly, equivalence is plainly not a good substitute for the loss of passporting.

Practical outlook

Whilst London will always have a strong financial centre given the large concentration of expertise it has in this area, the issue is the extent to which that status will be eroded. The attraction of London from an industry perspective is that an institution can use its London base to provide services to the whole of the EU: London effectively operates as a ‘one-stop shop’. Post-Brexit, this will no longer be the case: with the loss of passporting, there will be services that cannot be carried out from the UK and firms will need to establish a subsidiary within the EU to serve those markets. The required scale of the EU entity will depend on the view taken by the local regulator, but it could potentially be a sizeable, and therefore costly, operation. Just as London’s financial sector is likely to shrink in size, so the cost of business is also likely to rise, with the operational and regulatory complexities arising from having two offices to maintain. The extent to which businesses can absorb the additional costs is unclear; one suspects the cost will be passed back to the users of the service.

The fragmentation of services is not only problematic from a cost perspective, but also from a financial stability perspective. If an operation is split over a number of geographical locations that are subject to different regulatory regimes, it gives rise to questions of systemic risk. A chief driver behind the need for harmonisation in the regulation of financial services was the recognition that the regulation of financial institutions had to operate seamlessly at a global level. That rationale still remains. Hence, it is important that the UK and the EU maintain similar frameworks, which are mutually recognised.

Cost of doing business

The government’s desire to preserve passporting without acceding to free movement is ambitious. Given the EU’s current position that it is either a ‘hard’ Brexit or no Brexit, the EU will need a strong incentive to agree to this: one proposal the Cabinet is rumoured to be discussing is that in return for the preservation of passporting rights, Britain would continue to pay large sums into the EU budget. Whether this is politically acceptable remains to be seen, but it demonstrates that the government understands the importance of the financial markets to the UK economy.

If passporting rights cannot be preserved, the equivalence regime, even if extended, will not be a satisfactory alternative. It is likely therefore that UK firms seeking to do business within the EU will need to set up a subsidiary in the EU: there will be some degree of fragmentation in the way that companies operate, which will invariably lead to an increase in the cost of doing business. As Juncker noted after the referendum result, the relationship between the UK and the EU was never much of a‘love affair’, but with respect to financial services, it is seriously questionable whether divorce will result in a better outcome.

Contributor Saima Hanif, 39 Essex Chambers

As such, for the moment, the UK’s desired outcome seems unlikely to be achieved.

If access to the single market is not preserved, whilst London should continue to be a robust financial services centre, it will be weakened by the fragmentation of the services currently provided by UK financial institutions, as firms will have to maintain offices in both London and the EU. As a consequence, the regulatory burden and cost of doing business within the EU will increase.

Brexit options

Although the government has remained silent about what exactly Brexit will entail, it is safe to assume that the Swiss option and the Norwegian option will not be pursued, since both would require the UK to accept free movement of persons– and sovereignty over immigration is something that Theresa May’s government has explicitly prioritised as an outcome. At the same time, EU ministers have made clear on numerous occasions that the four freedoms are not separable: in the words of Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, ‘there can be no à la carte access to the single market’. If we take such proclamations at face value, then the UK will not be granted unrestricted access to the single market, with the result that financial services ‘passporting’ rights will not be preserved.

Passporting rights

The CRD IV (which contains the prudential rules for banks, building societies and investment firms) and MiFID (a directive which provides harmonised regulation for investment services) both contain a passporting regime, with the effect that an institution that is authorised and supervised by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)/Prudential Regulation Authority in London, is free to provide (or ‘passport’) those services into the EU, without needing to be separately regulated in each of the member states, or without having to establish a physical presence in that state. If a firm choses to have a physical presence, it can be in the form of a branch rather than a subsidiary, which does not need to be separately capitalised.

This has been a key attraction for non-EU institutions in particular, who have viewed London as a convenient gateway to the rest of Europe. Indeed, one of the specific requests in the memorandum published by the Japanese banks was ‘maintenance of the freedom of establishment and the provision of financial services, including the “single passport” system’. The memorandum noted that nearly half of all Japanese investment in the EU in 2015 went to the UK and the bulk of Japanese companies with an international presence have operations in the UK.

The FCA has also published data that shows that in respect of passporting, 5,476 UK firms hold one or more outbound passports to do business in the EU (see box). In short, the importance of passporting for the industry cannot be overstated.

If passporting rights are not preserved, UK firms providing services currently covered by the passport, will need to set up an authorised subsidiary within the EU and conduct EU business from that subsidiary. Depending on the expected volumes of trade, this could be a costly exercise as it could require the local presence of a sizeable workforce, and the establishment of appropriate systems and controls within the subsidiary. Correspondingly, EU banks that have branches in the UK may need to capitalise those separately for the first time; this is likely to be a huge cost for those institutions.

Equivalence

Once the UK has left the EU, it will become a third party country. The notion of ‘equivalence’ becomes relevant at this point. A number of EU directives contain provisions that enable firms in third party countries to provide services to the EU, without needing to be separately authorised by the EU regulator, as long as the regulatory ecosystem of that country is deemed to be ‘equivalent’ to that of the EU. Hence, at a superficial level, this appears to be a satisfactory alternative to the loss of passporting.

In truth, however, equivalence as it currently stands is a limited and piecemeal tool. The granting of equivalent status is principally a political decision, as it is the European Commission that has to issue a declaration of equivalence (albeit with input from technical agencies). The recognition of US clearing houses under EMIR, which took some three years to resolve, is an example of this. Moreover, the Commission can alter or withdraw a decision of equivalence at will, with little or no notice. In terms of ongoing equivalence, the UK would be tied to the EU regulatory framework, as it would have to ensure that any changes in the EU legislation were also reflected in the domestic legislation. Hence not only would the maintenance of an equivalence determination be uncertain, but politically, maintaining equivalence would, arguably, undermine the objective of leaving the EU in order to be ‘sovereign.’

It should also be noted that some directives do not contain any equivalence provisions at all (eg under the CRD IV, in respect of activities such as deposit-taking and lending there is no third country regime) – hence unless the equivalence regime were extended to cover these activities, there would be no alternative to the loss of passporting rights other than to establish a subsidiary within the EU. Even those directives that do contain equivalence provisions, are limited in their scope: whilst MiFID II/MiFIR has a specific third country regime (see Arts 46-49) the equivalence provisions only apply to the provision of investment services to per se professional clients and eligible counterparties: it does not cover retail investors or elective professional clients. Accordingly, equivalence is plainly not a good substitute for the loss of passporting.

Practical outlook

Whilst London will always have a strong financial centre given the large concentration of expertise it has in this area, the issue is the extent to which that status will be eroded. The attraction of London from an industry perspective is that an institution can use its London base to provide services to the whole of the EU: London effectively operates as a ‘one-stop shop’. Post-Brexit, this will no longer be the case: with the loss of passporting, there will be services that cannot be carried out from the UK and firms will need to establish a subsidiary within the EU to serve those markets. The required scale of the EU entity will depend on the view taken by the local regulator, but it could potentially be a sizeable, and therefore costly, operation. Just as London’s financial sector is likely to shrink in size, so the cost of business is also likely to rise, with the operational and regulatory complexities arising from having two offices to maintain. The extent to which businesses can absorb the additional costs is unclear; one suspects the cost will be passed back to the users of the service.

The fragmentation of services is not only problematic from a cost perspective, but also from a financial stability perspective. If an operation is split over a number of geographical locations that are subject to different regulatory regimes, it gives rise to questions of systemic risk. A chief driver behind the need for harmonisation in the regulation of financial services was the recognition that the regulation of financial institutions had to operate seamlessly at a global level. That rationale still remains. Hence, it is important that the UK and the EU maintain similar frameworks, which are mutually recognised.

Cost of doing business

The government’s desire to preserve passporting without acceding to free movement is ambitious. Given the EU’s current position that it is either a ‘hard’ Brexit or no Brexit, the EU will need a strong incentive to agree to this: one proposal the Cabinet is rumoured to be discussing is that in return for the preservation of passporting rights, Britain would continue to pay large sums into the EU budget. Whether this is politically acceptable remains to be seen, but it demonstrates that the government understands the importance of the financial markets to the UK economy.

If passporting rights cannot be preserved, the equivalence regime, even if extended, will not be a satisfactory alternative. It is likely therefore that UK firms seeking to do business within the EU will need to set up a subsidiary in the EU: there will be some degree of fragmentation in the way that companies operate, which will invariably lead to an increase in the cost of doing business. As Juncker noted after the referendum result, the relationship between the UK and the EU was never much of a‘love affair’, but with respect to financial services, it is seriously questionable whether divorce will result in a better outcome.

Contributor Saima Hanif, 39 Essex Chambers

How will losing passporting rights affect the UK’s financial services sector? Saima Hanif argues that the equivalence regime is not a satisfactory alternative

As the President of the European Council Donald Tusk remarked, in response to comments from Boris Johnson that the UK could have its cake and eat it by keeping single market access without accepting free movement of persons: ‘There will be no cakes on the table, for anyone. There will be only salt and vinegar…’

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar