*/

Not a golden oldie. David Langwallner continues his series with a rather controversial choice

Michael Gove has launched war on extremism and no doubt extremism is to be condemned. The question is, of course, what is an extremist? And, even more pertinent, how do we legislate to control the same from undermining democracy and the rule of law?

Not long ago I did a case in Huntingdon, the place of Oliver Cromwell’s birth. At one level the Glorious Revolution was an objection to extremism and a celebration of religious difference worth remembering in an age of extremes of witch hunts. Then as now.

Cromwell, noticeably, was not tolerant of witch hunts and in 1650 led an invasion force into Gove’s country of origin to stop the Kirk-led Scottish witch hunt. While in Huntingdon, I visited an exhibition marking the 375th anniversary of the visitation of one of the most sinister figures in 17th century history, the infamous and self-styled ‘Witchfinder General’ Matthew Hopkins.

Now, Witchfinder General is a controversial choice for this series and most decidedly not a golden oldie (in fact, it is a late 60s exercise in Grand Guignol). It is not easy viewing. The violence – well, even Quentin Tarantino might wince.

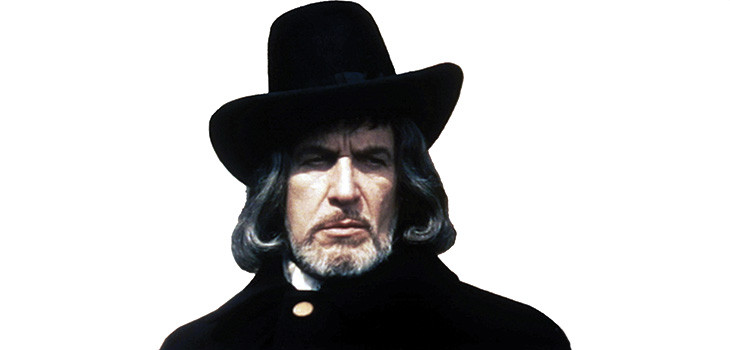

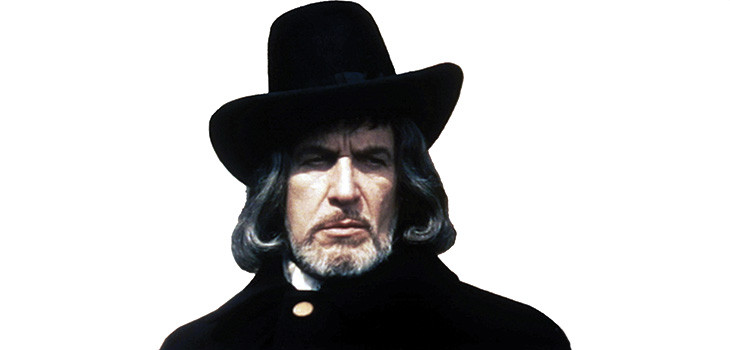

Directed by Michael Reeve and starring Vincent Price, the film follows Matthew Hopkins (Price) as self-styled ‘Witchfinder General’ travelling around East Anglia during the English Civil War hunting for witches and coercing confessions. Judge, jury and executioner wrapped in one. Whipping up mass hysteria in every town and village he visits to justify the interrogation, torture and execution of innocent people.

Hopkins is pursued around Eastern England by Roundhead soldier Richard Marshall (Ian Ogilvy) after he sets his wicked sights on Marshall’s fiancée Sara (Hilary Dwyer) and executes her uncle John Lowes (Rupert Davies).

As an aside, Hopkins is thought to have had some training as a lawyer (we have no evidence for this) and falsely claimed to have been appointed Witchfinder General by Parliament. He was well paid for his work which is said to have motivated his actions (Russell, Jeffrey B (1981), A History of Witchcraft, Thames & Hudson).

The most famous play about witch hunts is not Witchfinder General but Arthur Miller’s political allegory The Crucible (1953 – made into a film in 1996 by director Nicholas Hytner). In a recent production at the Gielgud Theatre there was an introduction in the programme by Stanley Schiff whose book The Salem Witch Hunt (2015) notes how in Freudian terms it was a conversion disorder which caused the hysteria of persecution and prosecution. Miller, cogently like a lawyer, after checking the trial record in Salem found that what was needed to convict was not corroboration of an actual act but spectral evidence. Much of the play is in fact in a court room where the dangling carrot of non-execution if a confession was made is clear.

Of course, Miller himself was targeted in the political witch hunt of the McCarthy Era as were many communist sympathisers or indeed even those with a slight leftist tinge. Consider this by Miller: ‘We are what we always were in Salem, but now the little crazy children are jangling the keys of the kingdom, and common vengeance writes the law!’

Legislatively targeting organisations for extremism is desperation. ‘Reds in our midst.’ And it is the little people who suffer the most and have the least resources to fight back. Not unlike the prosecution of sub-postmasters on a false Fujitsu system. Only after lives are destroyed does the establishment apologise.

I am also reminded of another linked film, Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) a horror story portraying a priest’s fall after being accused of witchcraft, fuelled by populist nonsense and vengeful prosecutorial overkill.

Witchfinder General became a cult classic, perhaps due to the director’s premature death just nine months after its release. It was a performance of transcendent madness by Price (he judged this his greatest performance) and was much-censored at the time. But worthy of inclusion in this series.

Michael Gove has launched war on extremism and no doubt extremism is to be condemned. The question is, of course, what is an extremist? And, even more pertinent, how do we legislate to control the same from undermining democracy and the rule of law?

Not long ago I did a case in Huntingdon, the place of Oliver Cromwell’s birth. At one level the Glorious Revolution was an objection to extremism and a celebration of religious difference worth remembering in an age of extremes of witch hunts. Then as now.

Cromwell, noticeably, was not tolerant of witch hunts and in 1650 led an invasion force into Gove’s country of origin to stop the Kirk-led Scottish witch hunt. While in Huntingdon, I visited an exhibition marking the 375th anniversary of the visitation of one of the most sinister figures in 17th century history, the infamous and self-styled ‘Witchfinder General’ Matthew Hopkins.

Now, Witchfinder General is a controversial choice for this series and most decidedly not a golden oldie (in fact, it is a late 60s exercise in Grand Guignol). It is not easy viewing. The violence – well, even Quentin Tarantino might wince.

Directed by Michael Reeve and starring Vincent Price, the film follows Matthew Hopkins (Price) as self-styled ‘Witchfinder General’ travelling around East Anglia during the English Civil War hunting for witches and coercing confessions. Judge, jury and executioner wrapped in one. Whipping up mass hysteria in every town and village he visits to justify the interrogation, torture and execution of innocent people.

Hopkins is pursued around Eastern England by Roundhead soldier Richard Marshall (Ian Ogilvy) after he sets his wicked sights on Marshall’s fiancée Sara (Hilary Dwyer) and executes her uncle John Lowes (Rupert Davies).

As an aside, Hopkins is thought to have had some training as a lawyer (we have no evidence for this) and falsely claimed to have been appointed Witchfinder General by Parliament. He was well paid for his work which is said to have motivated his actions (Russell, Jeffrey B (1981), A History of Witchcraft, Thames & Hudson).

The most famous play about witch hunts is not Witchfinder General but Arthur Miller’s political allegory The Crucible (1953 – made into a film in 1996 by director Nicholas Hytner). In a recent production at the Gielgud Theatre there was an introduction in the programme by Stanley Schiff whose book The Salem Witch Hunt (2015) notes how in Freudian terms it was a conversion disorder which caused the hysteria of persecution and prosecution. Miller, cogently like a lawyer, after checking the trial record in Salem found that what was needed to convict was not corroboration of an actual act but spectral evidence. Much of the play is in fact in a court room where the dangling carrot of non-execution if a confession was made is clear.

Of course, Miller himself was targeted in the political witch hunt of the McCarthy Era as were many communist sympathisers or indeed even those with a slight leftist tinge. Consider this by Miller: ‘We are what we always were in Salem, but now the little crazy children are jangling the keys of the kingdom, and common vengeance writes the law!’

Legislatively targeting organisations for extremism is desperation. ‘Reds in our midst.’ And it is the little people who suffer the most and have the least resources to fight back. Not unlike the prosecution of sub-postmasters on a false Fujitsu system. Only after lives are destroyed does the establishment apologise.

I am also reminded of another linked film, Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) a horror story portraying a priest’s fall after being accused of witchcraft, fuelled by populist nonsense and vengeful prosecutorial overkill.

Witchfinder General became a cult classic, perhaps due to the director’s premature death just nine months after its release. It was a performance of transcendent madness by Price (he judged this his greatest performance) and was much-censored at the time. But worthy of inclusion in this series.

Not a golden oldie. David Langwallner continues his series with a rather controversial choice

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar