*/

As private prosecutions become more popular, particularly in cases of fraud and deceit, here's a refresher on their workings and historical roots, by Lim Yee

In the 1700s and 1800s, private prosecution was the only system of prosecution available to most people (see box, right). By 1855 private prosecutions had become very rare and dropped out of use with the enactment of the Prosecution of Offences Act 1879. This Act laid the foundations for the creation of a national publicly funded police force and a central Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). Private prosecutions, however, are now beginning to re-emerge as a powerful tool for individuals and businesses who are caught in the court backlog and/or feel let down by the police, local authorities or the CPS.

The right to bring private prosecutions is preserved by s 6(1) of the Prosecution of Offences Act (POA) 1985 and long used by organisations such as the RSPCA. There are many advantages to private prosecutions in England and Wales today: individuals and companies may no longer have to rely on a police investigation; it is an alternative to civil claim; the outcome may be more effective in securing punishments and preventing further crimes; the prosecutor has more control over the proceedings; and it can be speedy, thereby saving costs as well.

In the confiscation case R (Virgin Media Ltd) v Zinga [2014] EWCA Crim 52, a private prosecution, the Court of Appeal confirmed that ‘the bringing of private prosecutions as an alternative to civil proceedings has become more common; some lawyers and some security management companies now advertise their capabilities at mounting private prosecutions and the advantages of private prosecution over civil proceedings’.

The court quoted from a factsheet published in 2013 by the Fraud Advisory Panel, a charity supported by lawyers, accountants and others on private prosecutions for fraud offences. This said: ‘A successful private prosecution can result in a criminal conviction and custodial sentence for the offender, and compensation being awarded to the victim. It can also send a powerful deterrent message to those considering engaging in criminal activity against the victim.’

Private prosecutions, however, can have their limitations. A private prosecutor may not be as competent as counsel at the criminal Bar in conducting complex and difficult prosecutions (specialist counsel at the criminal Bar can be sought and there is now a Private Prosecutors Association to promote best practice). Individuals and companies will have to perform their own investigations, and interested parties may use private prosecution as a tool for malicious prosecuting. The CPS has the discretion to take over a private prosecution and discontinue it as appropriate.

Rules and regulations have been introduced to regulate private prosecutors who are subject to the same obligations as public prosecutors. The duty to disclose is one of ‘full and frank disclosure’, including any materials that may be adverse to the prosecution’s case or in favour of the defendant’s case. Breach of any such obligation would be deemed to be an abuse of process, which will lead to a stay. In such a situation, the CPS would take over the proceeding or discontinue it in the interests of justice, ie if there would be an infringement of the defendant’s right to a fair trial.

Aside from the obligations of disclosure, private prosecutors also have to observe their duty to meet the Full Code Test for public interest. The court in R (Kay and another) v Leeds Magistrates’ Court [2018] 4 WLR 91 said: ‘(2) Advocates and solicitors who have the conduct of private prosecutions must observe the highest standards of integrity, of regard for the public interest and duty to act as a Minister for Justice in preference to the interests of the client who has instructed them to bring the prosecution – owing a duty to the court to ensure that the proceeding is fair.’

This is somewhat astounding; historically, public interest was never a requirement, as pointed out by Mitting J In Ewing v Davis [2007] 1 WLR 3223: ‘[I]n my analysis of the Victorian authorities, there never was any requirement that a private prosecutor had to demonstrate that it was in the public interest that he should bring a prosecution for an offence against the provision of a public general act.’

As mentioned above, the CPS has the power to take over a private prosecution (under s 6(2) of the Prosecution of Offences Act 1985) or discontinue it when it considers that the Full Code Test is not met, ie breach of duty of disclosure or lack of public interest. CPS guidance sets out such circumstances (see: bit.ly/3lqadFh). However, a decision by the CPS not to prosecute does not necessarily mean that the private prosecution is not in the public interest (see: Scopelight Ltd v Chief of Police for Northumbria [2009] EWCA Civ 1156).

Private prosecutions are now firmly back in trend. Private prosecutors should be fully aware that they carry the same duty as a public prosecutor and observe their duty to the court and remember that private prosecutions can be taken over by the CPS if they are found to be in breach of such obligations.

Rewind: the historical background to private prosecutions

Before the establishment of a publicly funded police force and prosecution service, apprehension and investigation were the sole responsibilities of the victims of crime, who would also usually play the role of a private prosecutor. There were three key means of assistance given to the private prosecutor:

The use of newspapers for advertising rewards, arrests, and obtaining expert evidence to assist the victim or the prosecutor in bringing a private prosecution against a suspect.

The development of toll-roads: particularly useful for tracking down suspects, whereby toll-gates became the points of surveillance (toll-keepers could watch for stolen horses or suspicious people).

Victims of crimes could join private prosecuting associations, and were then given the privilege to rely on regular patrols and specialisms of their fellow members.

Private prosecuting associations, however, were not obligated to provide free public service for prosecuting a suspect. This meant that while expenses for patrolling and arrest were funded by the public, the expense of prosecution was borne by the victims. The only exception was if those cases were of special importance to the Crown. Needless to say, this resulted in a number of serious consequences to maintaining an effective and accessible justice system.

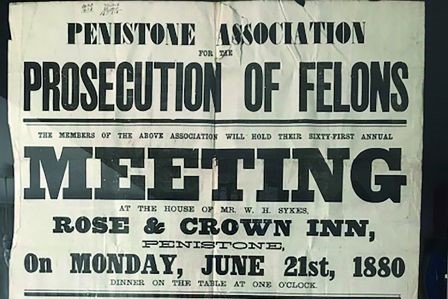

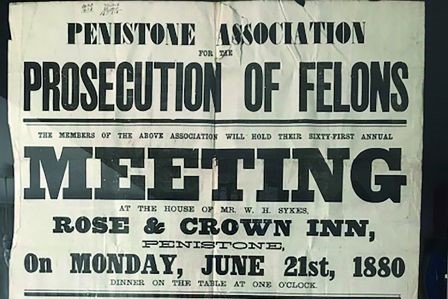

As a result, associations for the prosecution of felons were formed under which private bodies were established, from unincorporated companies to the Inns of Court. The associations offered a range of rewards and assisted in compliance with court decisions and payment of expenses.

This may have eased the costs of prosecution and improved the system of private prosecution, but contemporaries criticised their motives. For example, in a Birmingham case, the association prosecuted on behalf of a poor widow but kept the reward for getting a capital conviction and most of the costs awarded by the court.

In the 1830s, protests grew against private prosecution for its massive cost, inefficiency and use as a tool for malicious prosecution of innocent individuals by personally interested and elitist prosecutors. As a result, Parliament attempted to introduce a system of public prosecution in England. The prosecuting associations were abolished, especially after the county forces began work in 1856.

In the 20th century, the CPS was established after the enactment of Prosecution of Offences Act 1985. It replaced the system of private prosecution, with the responsibility to undertake all public prosecutions in England and Wales.

In the 1700s and 1800s, private prosecution was the only system of prosecution available to most people (see box, right). By 1855 private prosecutions had become very rare and dropped out of use with the enactment of the Prosecution of Offences Act 1879. This Act laid the foundations for the creation of a national publicly funded police force and a central Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). Private prosecutions, however, are now beginning to re-emerge as a powerful tool for individuals and businesses who are caught in the court backlog and/or feel let down by the police, local authorities or the CPS.

The right to bring private prosecutions is preserved by s 6(1) of the Prosecution of Offences Act (POA) 1985 and long used by organisations such as the RSPCA. There are many advantages to private prosecutions in England and Wales today: individuals and companies may no longer have to rely on a police investigation; it is an alternative to civil claim; the outcome may be more effective in securing punishments and preventing further crimes; the prosecutor has more control over the proceedings; and it can be speedy, thereby saving costs as well.

In the confiscation case R (Virgin Media Ltd) v Zinga [2014] EWCA Crim 52, a private prosecution, the Court of Appeal confirmed that ‘the bringing of private prosecutions as an alternative to civil proceedings has become more common; some lawyers and some security management companies now advertise their capabilities at mounting private prosecutions and the advantages of private prosecution over civil proceedings’.

The court quoted from a factsheet published in 2013 by the Fraud Advisory Panel, a charity supported by lawyers, accountants and others on private prosecutions for fraud offences. This said: ‘A successful private prosecution can result in a criminal conviction and custodial sentence for the offender, and compensation being awarded to the victim. It can also send a powerful deterrent message to those considering engaging in criminal activity against the victim.’

Private prosecutions, however, can have their limitations. A private prosecutor may not be as competent as counsel at the criminal Bar in conducting complex and difficult prosecutions (specialist counsel at the criminal Bar can be sought and there is now a Private Prosecutors Association to promote best practice). Individuals and companies will have to perform their own investigations, and interested parties may use private prosecution as a tool for malicious prosecuting. The CPS has the discretion to take over a private prosecution and discontinue it as appropriate.

Rules and regulations have been introduced to regulate private prosecutors who are subject to the same obligations as public prosecutors. The duty to disclose is one of ‘full and frank disclosure’, including any materials that may be adverse to the prosecution’s case or in favour of the defendant’s case. Breach of any such obligation would be deemed to be an abuse of process, which will lead to a stay. In such a situation, the CPS would take over the proceeding or discontinue it in the interests of justice, ie if there would be an infringement of the defendant’s right to a fair trial.

Aside from the obligations of disclosure, private prosecutors also have to observe their duty to meet the Full Code Test for public interest. The court in R (Kay and another) v Leeds Magistrates’ Court [2018] 4 WLR 91 said: ‘(2) Advocates and solicitors who have the conduct of private prosecutions must observe the highest standards of integrity, of regard for the public interest and duty to act as a Minister for Justice in preference to the interests of the client who has instructed them to bring the prosecution – owing a duty to the court to ensure that the proceeding is fair.’

This is somewhat astounding; historically, public interest was never a requirement, as pointed out by Mitting J In Ewing v Davis [2007] 1 WLR 3223: ‘[I]n my analysis of the Victorian authorities, there never was any requirement that a private prosecutor had to demonstrate that it was in the public interest that he should bring a prosecution for an offence against the provision of a public general act.’

As mentioned above, the CPS has the power to take over a private prosecution (under s 6(2) of the Prosecution of Offences Act 1985) or discontinue it when it considers that the Full Code Test is not met, ie breach of duty of disclosure or lack of public interest. CPS guidance sets out such circumstances (see: bit.ly/3lqadFh). However, a decision by the CPS not to prosecute does not necessarily mean that the private prosecution is not in the public interest (see: Scopelight Ltd v Chief of Police for Northumbria [2009] EWCA Civ 1156).

Private prosecutions are now firmly back in trend. Private prosecutors should be fully aware that they carry the same duty as a public prosecutor and observe their duty to the court and remember that private prosecutions can be taken over by the CPS if they are found to be in breach of such obligations.

Rewind: the historical background to private prosecutions

Before the establishment of a publicly funded police force and prosecution service, apprehension and investigation were the sole responsibilities of the victims of crime, who would also usually play the role of a private prosecutor. There were three key means of assistance given to the private prosecutor:

The use of newspapers for advertising rewards, arrests, and obtaining expert evidence to assist the victim or the prosecutor in bringing a private prosecution against a suspect.

The development of toll-roads: particularly useful for tracking down suspects, whereby toll-gates became the points of surveillance (toll-keepers could watch for stolen horses or suspicious people).

Victims of crimes could join private prosecuting associations, and were then given the privilege to rely on regular patrols and specialisms of their fellow members.

Private prosecuting associations, however, were not obligated to provide free public service for prosecuting a suspect. This meant that while expenses for patrolling and arrest were funded by the public, the expense of prosecution was borne by the victims. The only exception was if those cases were of special importance to the Crown. Needless to say, this resulted in a number of serious consequences to maintaining an effective and accessible justice system.

As a result, associations for the prosecution of felons were formed under which private bodies were established, from unincorporated companies to the Inns of Court. The associations offered a range of rewards and assisted in compliance with court decisions and payment of expenses.

This may have eased the costs of prosecution and improved the system of private prosecution, but contemporaries criticised their motives. For example, in a Birmingham case, the association prosecuted on behalf of a poor widow but kept the reward for getting a capital conviction and most of the costs awarded by the court.

In the 1830s, protests grew against private prosecution for its massive cost, inefficiency and use as a tool for malicious prosecution of innocent individuals by personally interested and elitist prosecutors. As a result, Parliament attempted to introduce a system of public prosecution in England. The prosecuting associations were abolished, especially after the county forces began work in 1856.

In the 20th century, the CPS was established after the enactment of Prosecution of Offences Act 1985. It replaced the system of private prosecution, with the responsibility to undertake all public prosecutions in England and Wales.

As private prosecutions become more popular, particularly in cases of fraud and deceit, here's a refresher on their workings and historical roots, by Lim Yee

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar