*/

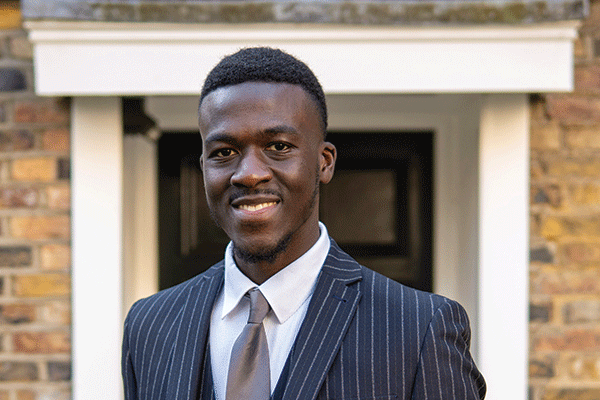

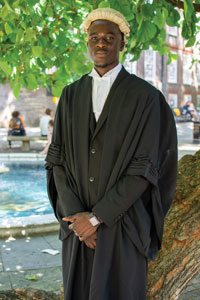

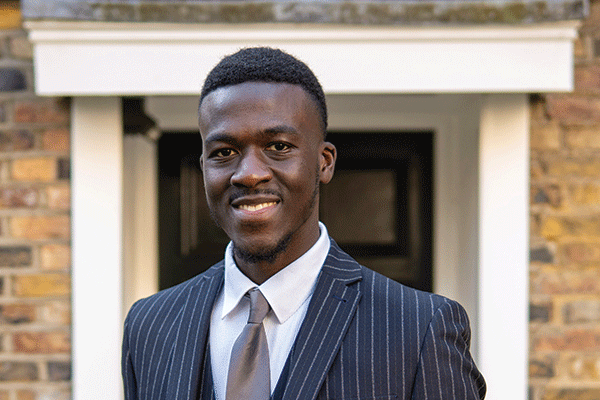

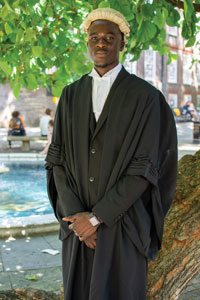

If all barristers try to ‘fit in’, we will alienate aspiring barristers from underrepresented groups: Mass Ndow-Njie on the importance of being visible

It was an ordinary morning. The sun rose, the alarm rang and the birds sang. He took a shower followed by his usual cup of coffee with milk and three teaspoons of sugar. Closing the door to his Parisian residence, he could see his driver waiting for him outside. His commute to the office was short. For some ambassadors, a trip to the office didn’t even require leaving the building. This was not because a lockdown forced them to work from home, but because the private residence is sometimes within the embassy building itself. Nevertheless, for him, the Gambian Ambassador to France, the office was just a short drive away.

On this regular Friday morning, on 22 July 1994, his secretary handed him a telex from the Gambian Foreign Ministry containing an unusual message. There was a mutiny under way in his home country. A group of soldiers had forbidden all civilian movement in parts of Banjul, the capital city of The Gambia. The soldiers were heading to the statehouse with weapons. The telex concluded, ‘the situation is being monitored and we will update you in due course’.

Later that evening he learned – alongside the rest of the world, via international news channels – that the coup d’état in The Gambia had been successful. The mutineers had assumed control of the country and a new era for The Gambia was about to begin. The country’s new leader would go on to rule as a dictator with an iron fist for the next 22 years. In the first months of that new era, the Gambian Ambassador to France was faced with a choice which would entirely shape the course of my life.

Within a short space of time he received two messages. One was from The Gambia communicating to him that he was to be recalled from his post and should return to Banjul. The second was from the deposed President of The Gambia, Sir Dawda Jawara. President Jawara called to invite the Ambassador to join him in the UK where he had recently emigrated following his exile from The Gambia. He urged the Ambassador to join his Council aiming to build support for the restoration of democracy within their beloved country.

The Ambassador’s whole life had been dedicated to public service. He had previously founded and commanded The Gambian National Army before being appointed as an Ambassador. Going back to Banjul would mean working under a repressive regime. Moreover, it would mean submitting himself and his family to an uncertain outcome given the mass arrests of senior officials who had served under President Jawara. The risks were very real. The alternative was to join the exiled President Jawara in England who he had known to respect the rule of law. Instead of taking the flight home to Banjul which was booked for him, he chose to cross the Channel and seek asylum in England. In making that decision, he chose to reject tyranny and secure the safety of his family over his own personal ambitions. He would have to leave everything behind and start again with nothing in a new country.

Months later, in early 1995, his wife gave birth to a bouncing baby boy in West Sussex, England. That baby was me, Mass Ndow-Njie, and in that moment I became the newest member of the family. When my family first arrived in England, they stayed with friends until they were granted asylum. My mother, previously a lecturer at The Gambia College School of Nursing and Midwifery, had to go back to bedside nursing and proudly worked for the NHS. My father also took on a range of driving jobs to ensure that collectively, they could support their young family.

I attended state schools. Private tuition was unaffordable and completely out of the question. Nonetheless, I was always urged to aim high academically. My mother often said: ‘I do not mind what you choose to do with your life, but whatever it is, make sure you get your degree. If you choose to become a cleaner, aim to study cleaning at university.’

My parents pushed me even further at home. Dad doubled up as my maths tutor on the weekends and Mum taught me science lessons in the evenings. I became accustomed to putting in extra time whenever it was necessary to achieve my goals. Even when I was achieving amongst the highest grades within my classes, my parents never allowed me to get carried away. They would regularly remind me that I was not competing against the other students within my class, but instead, I was competing against individuals who were excelling at schools all over the country. Just because I was not around them, it did not mean that they did not exist. I learned very early on that sometimes there is no alternative to putting in extra time. This has always helped me during exam seasons, and more recently, during pupillage where I was particularly keen to impress my supervisors. I wanted to prove to them that I belonged.

It is natural to want to fit into any space which you occupy. James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, noted that ‘the reward of being accepted is often greater than the reward of winning an argument, looking smart, or finding truth.’ I would go one step further and say that trying to fit in can often feel easier than being ourselves. But how could I fit in at the Bar? In my household, we usually spoke Wolof or Creole – common languages spoken across West Africa. We ate vibrant West African dishes, such as Benachin (or Jollof rice) and Domoda (peanut soup). My childhood is also full of memories of playing Gambian card games, such as ‘Scray’ and ‘Crazy 8’. The truth is, my culture is very different to that of most barristers practising in England and Wales.

Growing up, I would constantly try to hide my cultural nuances. I desperately wanted to be like everyone else. I was trying to emphasise the similarities I had with those around me as opposed to the differences. Yet, learning about different experiences and cultures is often valuable: it allows us to open our minds and broaden perspectives, both valuable traits for any barrister. Over time, I have learned to stop cloaking my differences and sharing this story is a part of that. I am proud of my unique background and unique culture. I don’t want to enter this profession if I feel compelled to adopt a new accent – I like my accent just as it is. I don’t want to pretend to have an interest in golf – I like playing football. More importantly, I don’t want to have to silence my story as it is the only story that I have.

Although I do not share the same cultural and educational background of many barristers already in the profession, I am equally qualified to practise. These qualifications do not require one to have a specific accent, sporting interest or to have taken a particular route into the profession. If all barristers try to ‘fit in’, then we will alienate aspiring barristers from underrepresented groups at the Bar. If we all adopt the same accent and claim to have the same interests, it will seem as if these things are hidden qualifications for the job. If we embrace ourselves, our unique stories and our varied cultures, we can create a ‘new normal’ in the profession. In this new normal, there will be no such thing as the ‘conventional’ image of a barrister. Instead, barristers will be as diverse as the society that we live in and as diverse as the clients that we represent. If you are a barrister from a non-traditional background, you can benefit so many aspiring barristers by simply sharing your story. Those aspiring barristers may be facing similar barriers to those you once faced yourself and may have similar interests to yours. Seeing that you have gained access to the profession sends the message that they can do it too. Thus, being visible is one of the most valuable gifts that you can give to them and social media helps to make that possible. They might see you and realise that they are not so different to you after all. Through you, they might see possibilities.

About Bridging the Bar

Bridging the Bar was launched as a charity in February 2020 to support students from non-traditional and underrepresented backgrounds to access the Bar. It was founded by Mass Ndow-Njie, and is now run by a 12-strong committee comprising barristers, aspiring and pupil barristers, as well as those who work in chambers and legal education.

So far, Bridging the Bar has raised over £60,000 from 20 sets of Chambers, including 11 founding partners: Blackstone Chambers, COMBAR, Hardwicke, Keating Chambers, 1 King’s Bench Walk, Littleton Chambers, 4 New Square, Normanton Chambers, Twenty Essex, Pump Court Tax Chambers and 3 Verulam Buildings.

Support for the charity has been even more widespread, with almost 60 sets of chambers and 300 individual volunteers (barristers, pupils, paralegals, solicitors, students, lecturers and even judges) offering a range of practical support and assistance. Among them is Amit Popat, Head of Equality and Access to Justice at the Bar Standards Board, who is running anti-bias training sessions for fellow Bridging the Bar volunteers.

A range of programmes and initiatives are now under development, including a judicial marshalling programme, a skills and education video training library and a diversity directory. The first of its flagship initiatives, a mentoring programme, launched last month and has already placed 75 students with individual barristers. More than 1,600 candidates have expressed an interest in the second initiative – offering mini-pupillages and hands-on experience of life at the Bar – and almost 60 sets of chambers have offered to host successful candidates.

The mini-pupillage application portal launched via the Bridging the Bar website on 7 December 2020. For further information please go to: www.bridgingthebar.org

It was an ordinary morning. The sun rose, the alarm rang and the birds sang. He took a shower followed by his usual cup of coffee with milk and three teaspoons of sugar. Closing the door to his Parisian residence, he could see his driver waiting for him outside. His commute to the office was short. For some ambassadors, a trip to the office didn’t even require leaving the building. This was not because a lockdown forced them to work from home, but because the private residence is sometimes within the embassy building itself. Nevertheless, for him, the Gambian Ambassador to France, the office was just a short drive away.

On this regular Friday morning, on 22 July 1994, his secretary handed him a telex from the Gambian Foreign Ministry containing an unusual message. There was a mutiny under way in his home country. A group of soldiers had forbidden all civilian movement in parts of Banjul, the capital city of The Gambia. The soldiers were heading to the statehouse with weapons. The telex concluded, ‘the situation is being monitored and we will update you in due course’.

Later that evening he learned – alongside the rest of the world, via international news channels – that the coup d’état in The Gambia had been successful. The mutineers had assumed control of the country and a new era for The Gambia was about to begin. The country’s new leader would go on to rule as a dictator with an iron fist for the next 22 years. In the first months of that new era, the Gambian Ambassador to France was faced with a choice which would entirely shape the course of my life.

Within a short space of time he received two messages. One was from The Gambia communicating to him that he was to be recalled from his post and should return to Banjul. The second was from the deposed President of The Gambia, Sir Dawda Jawara. President Jawara called to invite the Ambassador to join him in the UK where he had recently emigrated following his exile from The Gambia. He urged the Ambassador to join his Council aiming to build support for the restoration of democracy within their beloved country.

The Ambassador’s whole life had been dedicated to public service. He had previously founded and commanded The Gambian National Army before being appointed as an Ambassador. Going back to Banjul would mean working under a repressive regime. Moreover, it would mean submitting himself and his family to an uncertain outcome given the mass arrests of senior officials who had served under President Jawara. The risks were very real. The alternative was to join the exiled President Jawara in England who he had known to respect the rule of law. Instead of taking the flight home to Banjul which was booked for him, he chose to cross the Channel and seek asylum in England. In making that decision, he chose to reject tyranny and secure the safety of his family over his own personal ambitions. He would have to leave everything behind and start again with nothing in a new country.

Months later, in early 1995, his wife gave birth to a bouncing baby boy in West Sussex, England. That baby was me, Mass Ndow-Njie, and in that moment I became the newest member of the family. When my family first arrived in England, they stayed with friends until they were granted asylum. My mother, previously a lecturer at The Gambia College School of Nursing and Midwifery, had to go back to bedside nursing and proudly worked for the NHS. My father also took on a range of driving jobs to ensure that collectively, they could support their young family.

I attended state schools. Private tuition was unaffordable and completely out of the question. Nonetheless, I was always urged to aim high academically. My mother often said: ‘I do not mind what you choose to do with your life, but whatever it is, make sure you get your degree. If you choose to become a cleaner, aim to study cleaning at university.’

My parents pushed me even further at home. Dad doubled up as my maths tutor on the weekends and Mum taught me science lessons in the evenings. I became accustomed to putting in extra time whenever it was necessary to achieve my goals. Even when I was achieving amongst the highest grades within my classes, my parents never allowed me to get carried away. They would regularly remind me that I was not competing against the other students within my class, but instead, I was competing against individuals who were excelling at schools all over the country. Just because I was not around them, it did not mean that they did not exist. I learned very early on that sometimes there is no alternative to putting in extra time. This has always helped me during exam seasons, and more recently, during pupillage where I was particularly keen to impress my supervisors. I wanted to prove to them that I belonged.

It is natural to want to fit into any space which you occupy. James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, noted that ‘the reward of being accepted is often greater than the reward of winning an argument, looking smart, or finding truth.’ I would go one step further and say that trying to fit in can often feel easier than being ourselves. But how could I fit in at the Bar? In my household, we usually spoke Wolof or Creole – common languages spoken across West Africa. We ate vibrant West African dishes, such as Benachin (or Jollof rice) and Domoda (peanut soup). My childhood is also full of memories of playing Gambian card games, such as ‘Scray’ and ‘Crazy 8’. The truth is, my culture is very different to that of most barristers practising in England and Wales.

Growing up, I would constantly try to hide my cultural nuances. I desperately wanted to be like everyone else. I was trying to emphasise the similarities I had with those around me as opposed to the differences. Yet, learning about different experiences and cultures is often valuable: it allows us to open our minds and broaden perspectives, both valuable traits for any barrister. Over time, I have learned to stop cloaking my differences and sharing this story is a part of that. I am proud of my unique background and unique culture. I don’t want to enter this profession if I feel compelled to adopt a new accent – I like my accent just as it is. I don’t want to pretend to have an interest in golf – I like playing football. More importantly, I don’t want to have to silence my story as it is the only story that I have.

Although I do not share the same cultural and educational background of many barristers already in the profession, I am equally qualified to practise. These qualifications do not require one to have a specific accent, sporting interest or to have taken a particular route into the profession. If all barristers try to ‘fit in’, then we will alienate aspiring barristers from underrepresented groups at the Bar. If we all adopt the same accent and claim to have the same interests, it will seem as if these things are hidden qualifications for the job. If we embrace ourselves, our unique stories and our varied cultures, we can create a ‘new normal’ in the profession. In this new normal, there will be no such thing as the ‘conventional’ image of a barrister. Instead, barristers will be as diverse as the society that we live in and as diverse as the clients that we represent. If you are a barrister from a non-traditional background, you can benefit so many aspiring barristers by simply sharing your story. Those aspiring barristers may be facing similar barriers to those you once faced yourself and may have similar interests to yours. Seeing that you have gained access to the profession sends the message that they can do it too. Thus, being visible is one of the most valuable gifts that you can give to them and social media helps to make that possible. They might see you and realise that they are not so different to you after all. Through you, they might see possibilities.

About Bridging the Bar

Bridging the Bar was launched as a charity in February 2020 to support students from non-traditional and underrepresented backgrounds to access the Bar. It was founded by Mass Ndow-Njie, and is now run by a 12-strong committee comprising barristers, aspiring and pupil barristers, as well as those who work in chambers and legal education.

So far, Bridging the Bar has raised over £60,000 from 20 sets of Chambers, including 11 founding partners: Blackstone Chambers, COMBAR, Hardwicke, Keating Chambers, 1 King’s Bench Walk, Littleton Chambers, 4 New Square, Normanton Chambers, Twenty Essex, Pump Court Tax Chambers and 3 Verulam Buildings.

Support for the charity has been even more widespread, with almost 60 sets of chambers and 300 individual volunteers (barristers, pupils, paralegals, solicitors, students, lecturers and even judges) offering a range of practical support and assistance. Among them is Amit Popat, Head of Equality and Access to Justice at the Bar Standards Board, who is running anti-bias training sessions for fellow Bridging the Bar volunteers.

A range of programmes and initiatives are now under development, including a judicial marshalling programme, a skills and education video training library and a diversity directory. The first of its flagship initiatives, a mentoring programme, launched last month and has already placed 75 students with individual barristers. More than 1,600 candidates have expressed an interest in the second initiative – offering mini-pupillages and hands-on experience of life at the Bar – and almost 60 sets of chambers have offered to host successful candidates.

The mini-pupillage application portal launched via the Bridging the Bar website on 7 December 2020. For further information please go to: www.bridgingthebar.org

If all barristers try to ‘fit in’, we will alienate aspiring barristers from underrepresented groups: Mass Ndow-Njie on the importance of being visible

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar