*/

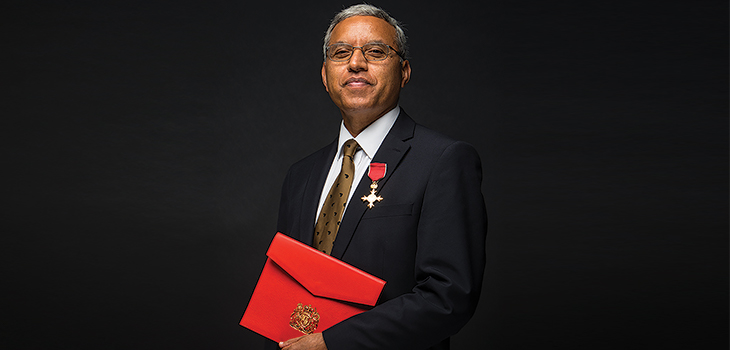

The journey from a small village in Nepal to international law professor and UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights: Admas Habteslasie talks to Surya Subedi QC (Hon)

The career of Professor Surya Subedi, Professor of International Law at Leeds University, has taken in both the theory and practice of international law, and human rights law in particular. Professor Subedi, who was appointed a QC honoris causa in 2017 and also practises from Three Stone Chambers in Lincoln’s Inn, speaks to me about Hindu principles, ‘zones of peace’ in international law and whether human rights were universal.

The foundations for Professor Subedi’s interest in human rights and international law were first lain in his childhood in Nepal, where, born in a small village, he received what he described as ‘a Sanskrit education informed by Hindu principles… universalism, tolerance, respect for personal liberty, secularism and non-violence’. After undertaking undergraduate law studies at Tribhuvan University in the Kathmandu Valley, Subedi began work in the international law office of the Government of Nepal. The complexity of the international law issues that he had to deal with awakened Subedi’s interest in international law, and also indicated to him how much more there was for him to learn; it was not long before his attention turned to the prospect of further study in international law.

Following the award of a scholarship, Subedi found himself transported from Nepal to Hull, where he undertook an LLM at the University of Hull. Following his LLM, Subedi returned to Nepal briefly before returning to the UK to complete doctoral studies at Oxford, and subsequently entered academia.

While he was a junior academic, a violent civil war broke out in his native Nepal. He recalls the effect this had on his views at the time: ‘it led me to explore how human rights could be strengthened and how the world could be made more peaceful... how could international law be used as an instrument to empower people… whether it was strong enough to do that’.

Some indication of Professor Subedi’s future professional interests was given in his 1993 doctoral thesis on ‘zones of peace’ (Land and Maritime Zones of Peace in International Law, 1993). In 1973, King Birendra of Nepal, addressing the Algiers Summit Conference of non-aligned nations, had said that ‘Nepal, situated between two most populous countries in the world, wishes within her frontiers to be enveloped in a zone of peace.’ (Nepal was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement, established in 1961 as a forum of developing world states that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc.) Subedi’s dissertation considered the international law dimensions of the concept of giving areas a status that insulated them from militarisation and outside interference. The context was the Cold War, and, in particular, an interest in how international law could be used to protect the autonomy and neutrality of developing nations, who often found their own interests subordinated to the zero-sum bipolar power politics of the time.

Professor Subedi has published on topics as diverse as territorial disputes, international investment law, military intervention in Libya and international human rights. A significant proportion of his work has a focus on east and central Asia. His most recent book, published in March 2021, is entitled Human Rights in Eastern Civilisations and examines the values of Eastern civilisations, in particular the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, with an eye to identifying parallels with the principles underpinning the international human rights framework. In the context of relativistic arguments that ‘Asian values’ represent an alternative to human rights, which, as Subedi observes, tend to be made to justify autocratic tendencies, the book is an argument that human rights in a rudimental form are to be found in all major civilisations, and are truly universal.

Professor Subedi has, throughout his career, combined academic work with more practical work in public international law. As a young academic, he undertook work for the Nepalese Royal Commission on Judicial Reform; he was an expert member of the Task Force on Investment Policy of the World Economic Forum and, in 2010, he was appointed by the British Government in 2010 to join the Foreign Secretary’s Advisory Group on Human Rights.

In 2009, Subedi was elected by the UN Human Rights Council to serve as the UN’s Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Cambodia for six years. The Special Rapporteur role was created in the wake of the horrific human rights abuses of the Cambodian-Vietnamese War, and the Rapporteur’s mandate, derived from the Paris Peace Accords that marked the end of that conflict, is to ‘monitor closely’ the human rights situation in Cambodia. Subedi describes the appointment, which required him to engage in fact-finding regarding breaches of human rights standards, engage with Cambodian civil society and work with senior Government officials and politicians, including the Prime Minister of Cambodia, as ‘a big departure’ from work as an academic. The role required a delicate balancing act: reporting on human rights shortcomings while, at the same time, ‘cajoling, reasoning’ with and criticising the host government in whose hands the prospect of meaningful change ultimately lay and of whom he was, by definition, a guest. Formidable diplomatic skills were required, and Professor Subedi reflects on whether his identity as Nepalese, a national of a country ‘sandwiched between two giants of Asia’, may have played some role in developing his diplomatic side. He produced four substantive reports as Special Rapporteur, dealing with judicial, parliamentary, electoral, and land reform in Cambodia. Many of his recommendations were ultimately implemented by the Cambodian government, including reforms to judicial appointments and changes to the Cambodian Constitution so as to place Cambodia’s National Election Committee, which supervises national elections, on a constitutional footing. He describes his work as Special Rapporteur as the work he is most proud of in his career.

Professor Subedi’s career also straddles academia and practice in that he practises as a barrister from chambers. He notes the strong overlap between the work of a legal academic and a barrister, describing barristers as ‘partly academics’, but emphasises that academics have the opportunity to ‘go one step further and ask what is wrong with the law and what ought to be changed’. Reflecting on differences between the experience of appearing before English judges and judges in international fora such as the International Court of Justice, Professor Subedi makes the (surely uncontroversial) observation that the former tend to be more adversarial, the latter more academic and ‘genteel’.

Subedi, who first came to the UK in his 20s, clearly has found himself very much at home in the worlds of academia and the Bar; he identifies a strong affinity between his own ethos and those of his colleagues in academia and the public law Bar in ‘promoting universalism, promoting secularism, strengthening personal liberty and bringing about fairness and justice to people both at home and abroad’. As a result, he is, in his words, ‘immensely happy to be working here, both in the legal profession and the academic world’.

The career of Professor Surya Subedi, Professor of International Law at Leeds University, has taken in both the theory and practice of international law, and human rights law in particular. Professor Subedi, who was appointed a QC honoris causa in 2017 and also practises from Three Stone Chambers in Lincoln’s Inn, speaks to me about Hindu principles, ‘zones of peace’ in international law and whether human rights were universal.

The foundations for Professor Subedi’s interest in human rights and international law were first lain in his childhood in Nepal, where, born in a small village, he received what he described as ‘a Sanskrit education informed by Hindu principles… universalism, tolerance, respect for personal liberty, secularism and non-violence’. After undertaking undergraduate law studies at Tribhuvan University in the Kathmandu Valley, Subedi began work in the international law office of the Government of Nepal. The complexity of the international law issues that he had to deal with awakened Subedi’s interest in international law, and also indicated to him how much more there was for him to learn; it was not long before his attention turned to the prospect of further study in international law.

Following the award of a scholarship, Subedi found himself transported from Nepal to Hull, where he undertook an LLM at the University of Hull. Following his LLM, Subedi returned to Nepal briefly before returning to the UK to complete doctoral studies at Oxford, and subsequently entered academia.

While he was a junior academic, a violent civil war broke out in his native Nepal. He recalls the effect this had on his views at the time: ‘it led me to explore how human rights could be strengthened and how the world could be made more peaceful... how could international law be used as an instrument to empower people… whether it was strong enough to do that’.

Some indication of Professor Subedi’s future professional interests was given in his 1993 doctoral thesis on ‘zones of peace’ (Land and Maritime Zones of Peace in International Law, 1993). In 1973, King Birendra of Nepal, addressing the Algiers Summit Conference of non-aligned nations, had said that ‘Nepal, situated between two most populous countries in the world, wishes within her frontiers to be enveloped in a zone of peace.’ (Nepal was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement, established in 1961 as a forum of developing world states that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc.) Subedi’s dissertation considered the international law dimensions of the concept of giving areas a status that insulated them from militarisation and outside interference. The context was the Cold War, and, in particular, an interest in how international law could be used to protect the autonomy and neutrality of developing nations, who often found their own interests subordinated to the zero-sum bipolar power politics of the time.

Professor Subedi has published on topics as diverse as territorial disputes, international investment law, military intervention in Libya and international human rights. A significant proportion of his work has a focus on east and central Asia. His most recent book, published in March 2021, is entitled Human Rights in Eastern Civilisations and examines the values of Eastern civilisations, in particular the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, with an eye to identifying parallels with the principles underpinning the international human rights framework. In the context of relativistic arguments that ‘Asian values’ represent an alternative to human rights, which, as Subedi observes, tend to be made to justify autocratic tendencies, the book is an argument that human rights in a rudimental form are to be found in all major civilisations, and are truly universal.

Professor Subedi has, throughout his career, combined academic work with more practical work in public international law. As a young academic, he undertook work for the Nepalese Royal Commission on Judicial Reform; he was an expert member of the Task Force on Investment Policy of the World Economic Forum and, in 2010, he was appointed by the British Government in 2010 to join the Foreign Secretary’s Advisory Group on Human Rights.

In 2009, Subedi was elected by the UN Human Rights Council to serve as the UN’s Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Cambodia for six years. The Special Rapporteur role was created in the wake of the horrific human rights abuses of the Cambodian-Vietnamese War, and the Rapporteur’s mandate, derived from the Paris Peace Accords that marked the end of that conflict, is to ‘monitor closely’ the human rights situation in Cambodia. Subedi describes the appointment, which required him to engage in fact-finding regarding breaches of human rights standards, engage with Cambodian civil society and work with senior Government officials and politicians, including the Prime Minister of Cambodia, as ‘a big departure’ from work as an academic. The role required a delicate balancing act: reporting on human rights shortcomings while, at the same time, ‘cajoling, reasoning’ with and criticising the host government in whose hands the prospect of meaningful change ultimately lay and of whom he was, by definition, a guest. Formidable diplomatic skills were required, and Professor Subedi reflects on whether his identity as Nepalese, a national of a country ‘sandwiched between two giants of Asia’, may have played some role in developing his diplomatic side. He produced four substantive reports as Special Rapporteur, dealing with judicial, parliamentary, electoral, and land reform in Cambodia. Many of his recommendations were ultimately implemented by the Cambodian government, including reforms to judicial appointments and changes to the Cambodian Constitution so as to place Cambodia’s National Election Committee, which supervises national elections, on a constitutional footing. He describes his work as Special Rapporteur as the work he is most proud of in his career.

Professor Subedi’s career also straddles academia and practice in that he practises as a barrister from chambers. He notes the strong overlap between the work of a legal academic and a barrister, describing barristers as ‘partly academics’, but emphasises that academics have the opportunity to ‘go one step further and ask what is wrong with the law and what ought to be changed’. Reflecting on differences between the experience of appearing before English judges and judges in international fora such as the International Court of Justice, Professor Subedi makes the (surely uncontroversial) observation that the former tend to be more adversarial, the latter more academic and ‘genteel’.

Subedi, who first came to the UK in his 20s, clearly has found himself very much at home in the worlds of academia and the Bar; he identifies a strong affinity between his own ethos and those of his colleagues in academia and the public law Bar in ‘promoting universalism, promoting secularism, strengthening personal liberty and bringing about fairness and justice to people both at home and abroad’. As a result, he is, in his words, ‘immensely happy to be working here, both in the legal profession and the academic world’.

The journey from a small village in Nepal to international law professor and UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights: Admas Habteslasie talks to Surya Subedi QC (Hon)

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar