*/

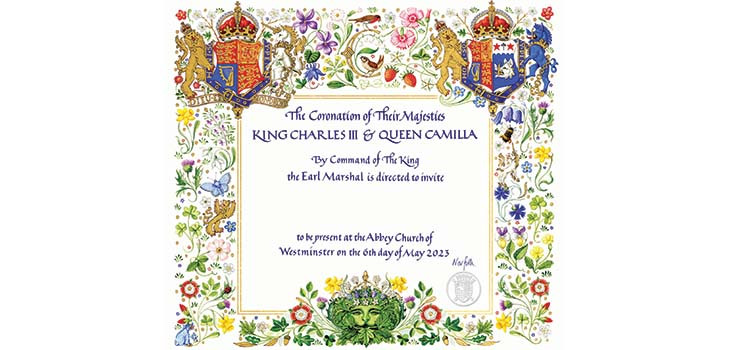

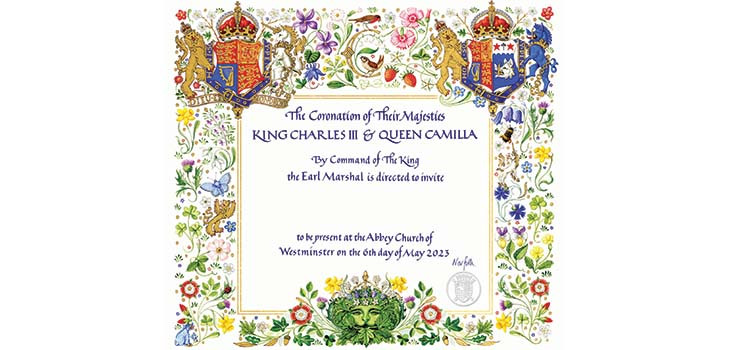

In popular discourse, and occasionally even in the media, there is considerable confusion about what a coronation actually represents. The biggest misunderstanding is that the ceremony somehow represents the beginning of a new monarch’s reign. But the Prince of Wales is not being crowned on 6 May 2023, King Charles III is. Through a combination of common law and statute, Charles became monarch the moment his late mother passed away on 8 September 2022.

Rather, the coronation is primarily a religious ceremony, an Anglican service to anoint someone who is already Sovereign. The legal or constitutional content of a modern coronation ceremony is actually minimal, consisting of one and sometimes two statutory oaths (this article is not concerned with the Accession Declaration Oath). As the short reign of King Edward VIII in 1936 demonstrates, a coronation need not happen at all.

The Coronation Oath is always taken. The Coronation Oath Act 1689 provided for a single uniform oath to be taken by King William III and Queen Mary II and by all future monarchs. The oath was reiterated in s 2 of the (English) Act of Settlement 1701, later extended to Scotland (as part of the new ‘united Kingdom’ of Great Britain) by virtue of Article II of the Treaty of Union.

Section III of the 1689 Act provided the form of the oath and its administration, while s IV provided that it should be administered (read) to the monarch by the Archbishop of Canterbury or York ‘in the Presence of all Persons that shall be Attending Assisting or otherwise present at such their respective Coronations’.

Initially, care was taken explicitly to amend the wording of the oath. Section II of a 1706 Act of the English Parliament ‘for securing the Church of England as by Law established’ extended the third part of the Oath, while ‘this Kingdom of England’ was impliedly changed via the 1706-07 Acts of Union. When King George I took his Coronation Oath in 1714, he referred not to England but to ‘Great Britain’.

Further implied amendments were made to the oath taken by King George IV in 1821. Not only was ‘Great Britain’ replaced with ‘the United Kingdom’ (reflecting the 1801 Union between Great Britain and Ireland) but the third part of the oath now included a promise to maintain the settlement of the ‘united church of England and Ireland’ (the Fifth Article of the Union with Ireland Act 1800 having united the two churches).

Reference to the ‘united church’ was removed from King Edward VII’s Coronation Oath in 1902 by virtue of s 69 of the Irish Church Act 1869, the whole Act having disestablished the Anglican church in Ireland.

Changes to the oath became much less straightforward during the rest of the 20th century. The big change was the Statute of Westminster 1931, which recognised the legislative independence of the Dominions from the ‘Imperial’ Parliament. Asked for his opinion, the Lord Chancellor (Lord Hailsham) stated that:

since the form of the Coronation Oath is laid down by Statute it cannot be altered without statutory authority. But it has always been recognised that if a statute is passed altering the constitutional position of this country in such a way as to render the words of the original Oath no longer applicable, that Act may be in the wording of the Oath.

This could be viewed as a post-hoc rationalisation of the changes outlined above. Nevertheless, Hailsham was of the view that any future revisions must ‘be limited to what was essential to give effect to the alteration in the constitutional position’.

The first part of King George VI’s oath was therefore altered to ‘according to their respective laws and customs’, thereby acknowledging that there now existed several sovereign parliaments (Graeme Watt has argued that this was unlawful given there was neither implied nor express repeal). The third part of the oath was also split into a general promise to maintain the laws of God and true profession of the Gospel, and a promise to maintain only in the UK the ‘protestant reformed religion’, thus acknowledging that only England and Scotland possessed established churches.

Thus, on 12 May 1937, the Archbishop of Canterbury invited George VI to:

solemnly promise and swear to govern the peoples of Great Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Union of South Africa, of your Possessions and the other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, and of your Empire of India, according to their respective Laws and Customs.

While the ‘Great Britain, Ireland’ formulation was covered by a Proclamation issued under the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927, the other realms were added via another Proclamation dated 13 February 1937. This was questionable given that statute law cannot be altered by the prerogative.

By 1953, suggestions that previous alterations to the Coronation Oath had lacked legal authority had grown to the extent that the National Archives boast several lengthy memoranda regarding the changes necessary for Queen Elizabeth II’s oath. In one Lord Simonds, the then Lord Chancellor, confidently declared that Hailsham’s opinion on implied amendment could ‘be used about all the amendments of substance that have at various times been made without statutory authority’.

Simonds also addressed the question as to whether it was ‘proper for such high matters to be disposed of except with the authority of Parliament’. This had also been considered in 1936-37 but given that legislation at Westminster would now have to be echoed in each Dominion legislature, the idea was abandoned on logistical grounds. Given the revised oath had been put to all the relevant governments and none had dissented, Simonds proposed to ‘leave it’ there.

In February 1953, Winston Churchill told the House of Commons that no legislation would be necessary in order to remove Ireland and India from, and add Pakistan and Ceylon to, the Queen’s Coronation Oath and that, in any case, there was no available time in which to legislate. The list of ‘Peoples’ in the first part of the oath was again altered without legislation.

It has been a long time since the last coronation, almost 70 years. While internal constitutional changes to the United Kingdom (ie devolution) do not require acknowledgement in the oath, external changes arguably do. Pakistan became a republic in 1956, as did the Union of South Africa in 1961 and Sri Lanka in 1972. Furthermore, there are now 14 Commonwealth Realms, independent states where King Charles III is also head of state. In a written statement on 19 April 2023, Oliver Dowden, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, announced that King Charles III’s oath would refer to these ‘collectively’ rather than individually.

Mr Dowden also made clear that the government intends to follow the precedents of 1937 and 1953 and make any necessary changes without recourse to Parliament. If the logistics of having every Realm legislate separately was considered too great at the last two coronations, it is considerably greater in 2023. Even one of the justifications provided in 1953 – lack of legislative time – has been revived. As yet unconfirmed, meanwhile, is speculation that the King will add a ‘supplementary declaration’ to his oath in order to affirm his belief in the divinity of other religions.

In popular discourse, and occasionally even in the media, there is considerable confusion about what a coronation actually represents. The biggest misunderstanding is that the ceremony somehow represents the beginning of a new monarch’s reign. But the Prince of Wales is not being crowned on 6 May 2023, King Charles III is. Through a combination of common law and statute, Charles became monarch the moment his late mother passed away on 8 September 2022.

Rather, the coronation is primarily a religious ceremony, an Anglican service to anoint someone who is already Sovereign. The legal or constitutional content of a modern coronation ceremony is actually minimal, consisting of one and sometimes two statutory oaths (this article is not concerned with the Accession Declaration Oath). As the short reign of King Edward VIII in 1936 demonstrates, a coronation need not happen at all.

The Coronation Oath is always taken. The Coronation Oath Act 1689 provided for a single uniform oath to be taken by King William III and Queen Mary II and by all future monarchs. The oath was reiterated in s 2 of the (English) Act of Settlement 1701, later extended to Scotland (as part of the new ‘united Kingdom’ of Great Britain) by virtue of Article II of the Treaty of Union.

Section III of the 1689 Act provided the form of the oath and its administration, while s IV provided that it should be administered (read) to the monarch by the Archbishop of Canterbury or York ‘in the Presence of all Persons that shall be Attending Assisting or otherwise present at such their respective Coronations’.

Initially, care was taken explicitly to amend the wording of the oath. Section II of a 1706 Act of the English Parliament ‘for securing the Church of England as by Law established’ extended the third part of the Oath, while ‘this Kingdom of England’ was impliedly changed via the 1706-07 Acts of Union. When King George I took his Coronation Oath in 1714, he referred not to England but to ‘Great Britain’.

Further implied amendments were made to the oath taken by King George IV in 1821. Not only was ‘Great Britain’ replaced with ‘the United Kingdom’ (reflecting the 1801 Union between Great Britain and Ireland) but the third part of the oath now included a promise to maintain the settlement of the ‘united church of England and Ireland’ (the Fifth Article of the Union with Ireland Act 1800 having united the two churches).

Reference to the ‘united church’ was removed from King Edward VII’s Coronation Oath in 1902 by virtue of s 69 of the Irish Church Act 1869, the whole Act having disestablished the Anglican church in Ireland.

Changes to the oath became much less straightforward during the rest of the 20th century. The big change was the Statute of Westminster 1931, which recognised the legislative independence of the Dominions from the ‘Imperial’ Parliament. Asked for his opinion, the Lord Chancellor (Lord Hailsham) stated that:

since the form of the Coronation Oath is laid down by Statute it cannot be altered without statutory authority. But it has always been recognised that if a statute is passed altering the constitutional position of this country in such a way as to render the words of the original Oath no longer applicable, that Act may be in the wording of the Oath.

This could be viewed as a post-hoc rationalisation of the changes outlined above. Nevertheless, Hailsham was of the view that any future revisions must ‘be limited to what was essential to give effect to the alteration in the constitutional position’.

The first part of King George VI’s oath was therefore altered to ‘according to their respective laws and customs’, thereby acknowledging that there now existed several sovereign parliaments (Graeme Watt has argued that this was unlawful given there was neither implied nor express repeal). The third part of the oath was also split into a general promise to maintain the laws of God and true profession of the Gospel, and a promise to maintain only in the UK the ‘protestant reformed religion’, thus acknowledging that only England and Scotland possessed established churches.

Thus, on 12 May 1937, the Archbishop of Canterbury invited George VI to:

solemnly promise and swear to govern the peoples of Great Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Union of South Africa, of your Possessions and the other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, and of your Empire of India, according to their respective Laws and Customs.

While the ‘Great Britain, Ireland’ formulation was covered by a Proclamation issued under the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927, the other realms were added via another Proclamation dated 13 February 1937. This was questionable given that statute law cannot be altered by the prerogative.

By 1953, suggestions that previous alterations to the Coronation Oath had lacked legal authority had grown to the extent that the National Archives boast several lengthy memoranda regarding the changes necessary for Queen Elizabeth II’s oath. In one Lord Simonds, the then Lord Chancellor, confidently declared that Hailsham’s opinion on implied amendment could ‘be used about all the amendments of substance that have at various times been made without statutory authority’.

Simonds also addressed the question as to whether it was ‘proper for such high matters to be disposed of except with the authority of Parliament’. This had also been considered in 1936-37 but given that legislation at Westminster would now have to be echoed in each Dominion legislature, the idea was abandoned on logistical grounds. Given the revised oath had been put to all the relevant governments and none had dissented, Simonds proposed to ‘leave it’ there.

In February 1953, Winston Churchill told the House of Commons that no legislation would be necessary in order to remove Ireland and India from, and add Pakistan and Ceylon to, the Queen’s Coronation Oath and that, in any case, there was no available time in which to legislate. The list of ‘Peoples’ in the first part of the oath was again altered without legislation.

It has been a long time since the last coronation, almost 70 years. While internal constitutional changes to the United Kingdom (ie devolution) do not require acknowledgement in the oath, external changes arguably do. Pakistan became a republic in 1956, as did the Union of South Africa in 1961 and Sri Lanka in 1972. Furthermore, there are now 14 Commonwealth Realms, independent states where King Charles III is also head of state. In a written statement on 19 April 2023, Oliver Dowden, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, announced that King Charles III’s oath would refer to these ‘collectively’ rather than individually.

Mr Dowden also made clear that the government intends to follow the precedents of 1937 and 1953 and make any necessary changes without recourse to Parliament. If the logistics of having every Realm legislate separately was considered too great at the last two coronations, it is considerably greater in 2023. Even one of the justifications provided in 1953 – lack of legislative time – has been revived. As yet unconfirmed, meanwhile, is speculation that the King will add a ‘supplementary declaration’ to his oath in order to affirm his belief in the divinity of other religions.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar