*/

Justice Ginsburg, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, passed away on 18 September 2020. She was one of the finest judges of her generation and a towering legal figure, in both national and international terms.

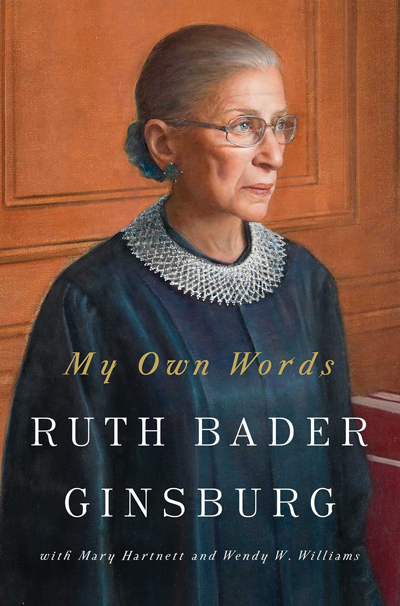

I had the privilege of meeting Justice Ginsburg on a number of occasions. On the last occasion that I saw her, Justice Ginsburg gave me a copy of her autobiography, My Own Words, with a moving personal message handwritten inside. It is a selfless work, giving little hint of the considerable, now well-known, discrimination that she personally experienced in her legal career.

But that discrimination had an influence on her approach. She once told USA Today that: ‘Anybody who has been discriminated against, who comes from a group that has been discriminated against, knows what it’s like.’ She is often remembered as the Justice who ‘did more to advance women’s rights than any other figure in modern US history’ (Edward Luce, Financial Times, 17 October 2020). She certainly delivered opinions which strongly supported women’s rights, though it would be wrong to suggest that they alone were the reason for her outstanding reputation.

I would liken the experience of reading this now much-treasured book to an imagined visit to the home of Justice Ginsburg, where she opens the door and warmly invites you inside. The autobiography begins with the story of her early life and modest upbringing. She gives a touching account of her relationship with her parents, particularly her mother, who died of cancer just as Ruth Bader, as she then was, was graduating from high school. Despite her struggle to get into law school, which admitted very few women students in those days, in the end she was awarded a place and achieved very high marks.

In My Own Words, Justice Ginsburg paid tribute to the lives of other lawyers, mostly women. For example, Belva Lockwood, the first woman member of the Supreme Court Bar, was an advocate for the first and last time in 1906, when, at the astonishing age of 75, she won a claim for compensation for the East Cherokee Indians.

After her university career, and some unsuccessful attempts to gain employment in a law firm, Justice Ginsburg became a professor of law. After that she headed the Women’s Rights Project, which was set up by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to generate rulings that statutes which discriminated against women were unconstitutional. One of the cases in which the ACLU took part was Frontiero v Richardson 411 US 677 (1973) where families of a woman member of the armed forces received a smaller package of employment benefits than families where that member was a man. The book includes the reply brief submitted to the Supreme Court which was inspired by the future Justice’s thinking. While unsuccessful in this respect in Frontiero, we read that the Women’s Project, with the future Justice at the helm, ultimately persuaded the Supreme Court to adopt a more rigorous approach than previously in sex discrimination cases.

Pursuing my simile of being a guest in Justice Ginsburg’s home, we are next invited into the kitchen. There is a very special reason for choosing this room. An important event occurred in Justice Ginsburg’s life when she was at law school. She met another able student whom she ultimately married. He was Marty Ginsburg, later a distinguished tax lawyer. He was the person who inspired and encouraged her until his untimely death in 2010. He was indeed a famed cook among family and friends. The kitchen was his domain – a manifestation of the rejection of the stereotypical image about women that they are always the ones to be in charge of the family kitchen and meals. Marty Ginsburg was also witty. There is even one of his speeches about Justice Ginsburg in the book.

Next, pursuing my simile, we move into the study where we can sit in an easy chair. Justice Ginsburg here gave some insight into the work of a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. I will give just a few examples. From the other side of the Atlantic we wonder at how the Supreme Court gets to the bottom of cases with a hearing in which oral argument is only about 30 minutes each side. The secret, she explained, was that the hearing is like a conversation:

‘Oral argument is not an occasion for grand speech making, but a conversation about the case, a dialogue or discussion between knowledgeable counsel and judges who have done their homework…’ (Part 5, Chapter 1, Workways of the Supreme Court)

Justice Ginsburg was not diverted by the pressure of media publicity that may surround a particular case. She explained how judges deal with current issues or political preoccupations. She wrote:

‘Judges do read newspapers and are affected not by the weather of day, as distinguished constitutional law Professor Paul Freund once said, but by the climate of the era.’ (Part 3, Chapter 6, Advocating the Elimination of Gender-Based Discrimination)

She did not just reject the opinions of those who disagreed with her views but used other Justices’ views to test and improve her own. Thus, in relation to dissenting opinions, she wrote:

‘My experience confirms that there is nothing better than an impressive dissent to lead the author of the majority opinion to define and clarify her initial circulation.’ (Part 5, Chapter 7, The Role of Dissenting Opinions)

There are many times when an appellate court finds that a person ought to have a remedy, but the legislature has done nothing to change the law to enable this to happen. Sometimes judges have to take some step or speak out in that situation. But the essence of the common law is that change is brought about little by little. Sometimes, rather than make an immediate change, judges will signal the need for change at some undetermined time in the future. I think that is what Justice Ginsburg meant when she wrote of the Supreme Court occasionally stepping out in front of the political process but in other contexts placing path markers before finally confronting a major issue (Part 5, Chapter 4, The Madison lecture: Speaking in Judicial Voice, pp 244 to 247).

Justice Ginsburg wrote about progression in the law through a series of cases. Perhaps her approach had something to do with her famed love of opera. Complex cases absorb our attention utterly, we learn from them, but we know that with a loud rumbling they are decided and then gone, and the scene is changed. We move on to meet the challenge of another day, when we shall surely have to grapple with new cases. Maybe this is why Justice Ginsburg was such a fan of opera. Indeed, she even appeared in performances of operas.

Sitting in the study (as it were) we can hear the lectures that have been reprinted in the second half of the book. One example is A Decent Respect to the Opinions of [Human]Kind’, which discusses the benefit of the study of constitutional law on a comparative basis, that is, by considering the experience of other countries that have had to deal with similar constitutional issues.

Justice Ginsburg was very quietly spoken. That made all her listeners concentrate very hard on what she was saying. I vividly recall her concise, considered and penetrating comments and questions. She had one of the sharpest legal minds. She respected precedent, and used rational argument to reach her conclusions. She did not display any arrogance but remained considerate and humble. James Zirin wrote in the New York Post: ‘She gave us faith in the Court, which so often seeks to resolve our nation’s deepest controversies. She recognized the wisdom of Justice Robert Jackson who said of the Court, “we are not final because we are infallible, we are infallible only because we are final”.’

Overall, My Own Words is a revealing read. When the time came to put the book down and leave that study, I felt that I had shared some time in the presence of Justice Ginsburg and learnt more about her distinguished career and driving ideas, and also about the way the US Supreme Court works.

In 2015, Justice Ginsburg and Lady Hale wrote a joint Foreword for my own book, Common Law and Modern Society: Keeping pace with change. I was greatly honoured. The Foreword ends with the intriguing statement: that the book should encourage readers to play a useful part in shaping tomorrow’s law. The Foreword gives no clue as to who those readers might be. Nor does the Foreword say, as I had indicated in my book, that it is the task of the judiciary to keep the common law up to date. But I have no doubt that Justice Ginsburg was sympathetic to that approach.

Justice Ginsburg loved the law. She gave advice to young women, which is often quoted, encouraging them to become lawyers and aim for the bench. Justice Ginsburg supported the cause of women in many fields of life, and was sensitive to the gender dimensions of her judicial work. So her autobiography is obviously a perfect volume for a young woman lawyer, whatever her aspirations, but it is also a wonderful read for anyone who wants to know more about the Supreme Court of the United States.

Less well-known are Justice Ginsburg’s views about the professional obligations of legal practitioners. These may also be of interest to readers of Counsel. In a joint interview with Baroness Hale, immediate past President of the UK Supreme Court, arranged by Georgetown University in 2008 (which can be accessed on YouTube and is worth watching in full: bit.ly/32QHVvz), she explained her high expectations of legal practitioners. These followed her vision for the role of law and justice in society.

Her words were thoughtful and reflected her sense of purpose. They are worth remembering and quoting in our everyday lives, and so I end this appreciation of Justice Ginsburg by quoting them:

‘To me the highest obligation of someone in the legal profession is to recognise that you have training and talent… that equip you to make things a little better in your local community, your nation and your world, that is, to devote your talent not just to being the counterpart of an artisan or bricklayer who does a day’s work for a day’s pay but with someone who sees himself or herself as a true citizen of the community.’

© Lady Arden November 2020

My Own Words by Ruth Bader Ginsburg (with Mary Hartnett and Wendy W Williams)

Publisher: Simon & Schuster 2018

ISBN: 9781501145254

Justice Ginsburg, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, passed away on 18 September 2020. She was one of the finest judges of her generation and a towering legal figure, in both national and international terms.

I had the privilege of meeting Justice Ginsburg on a number of occasions. On the last occasion that I saw her, Justice Ginsburg gave me a copy of her autobiography, My Own Words, with a moving personal message handwritten inside. It is a selfless work, giving little hint of the considerable, now well-known, discrimination that she personally experienced in her legal career.

But that discrimination had an influence on her approach. She once told USA Today that: ‘Anybody who has been discriminated against, who comes from a group that has been discriminated against, knows what it’s like.’ She is often remembered as the Justice who ‘did more to advance women’s rights than any other figure in modern US history’ (Edward Luce, Financial Times, 17 October 2020). She certainly delivered opinions which strongly supported women’s rights, though it would be wrong to suggest that they alone were the reason for her outstanding reputation.

I would liken the experience of reading this now much-treasured book to an imagined visit to the home of Justice Ginsburg, where she opens the door and warmly invites you inside. The autobiography begins with the story of her early life and modest upbringing. She gives a touching account of her relationship with her parents, particularly her mother, who died of cancer just as Ruth Bader, as she then was, was graduating from high school. Despite her struggle to get into law school, which admitted very few women students in those days, in the end she was awarded a place and achieved very high marks.

In My Own Words, Justice Ginsburg paid tribute to the lives of other lawyers, mostly women. For example, Belva Lockwood, the first woman member of the Supreme Court Bar, was an advocate for the first and last time in 1906, when, at the astonishing age of 75, she won a claim for compensation for the East Cherokee Indians.

After her university career, and some unsuccessful attempts to gain employment in a law firm, Justice Ginsburg became a professor of law. After that she headed the Women’s Rights Project, which was set up by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to generate rulings that statutes which discriminated against women were unconstitutional. One of the cases in which the ACLU took part was Frontiero v Richardson 411 US 677 (1973) where families of a woman member of the armed forces received a smaller package of employment benefits than families where that member was a man. The book includes the reply brief submitted to the Supreme Court which was inspired by the future Justice’s thinking. While unsuccessful in this respect in Frontiero, we read that the Women’s Project, with the future Justice at the helm, ultimately persuaded the Supreme Court to adopt a more rigorous approach than previously in sex discrimination cases.

Pursuing my simile of being a guest in Justice Ginsburg’s home, we are next invited into the kitchen. There is a very special reason for choosing this room. An important event occurred in Justice Ginsburg’s life when she was at law school. She met another able student whom she ultimately married. He was Marty Ginsburg, later a distinguished tax lawyer. He was the person who inspired and encouraged her until his untimely death in 2010. He was indeed a famed cook among family and friends. The kitchen was his domain – a manifestation of the rejection of the stereotypical image about women that they are always the ones to be in charge of the family kitchen and meals. Marty Ginsburg was also witty. There is even one of his speeches about Justice Ginsburg in the book.

Next, pursuing my simile, we move into the study where we can sit in an easy chair. Justice Ginsburg here gave some insight into the work of a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. I will give just a few examples. From the other side of the Atlantic we wonder at how the Supreme Court gets to the bottom of cases with a hearing in which oral argument is only about 30 minutes each side. The secret, she explained, was that the hearing is like a conversation:

‘Oral argument is not an occasion for grand speech making, but a conversation about the case, a dialogue or discussion between knowledgeable counsel and judges who have done their homework…’ (Part 5, Chapter 1, Workways of the Supreme Court)

Justice Ginsburg was not diverted by the pressure of media publicity that may surround a particular case. She explained how judges deal with current issues or political preoccupations. She wrote:

‘Judges do read newspapers and are affected not by the weather of day, as distinguished constitutional law Professor Paul Freund once said, but by the climate of the era.’ (Part 3, Chapter 6, Advocating the Elimination of Gender-Based Discrimination)

She did not just reject the opinions of those who disagreed with her views but used other Justices’ views to test and improve her own. Thus, in relation to dissenting opinions, she wrote:

‘My experience confirms that there is nothing better than an impressive dissent to lead the author of the majority opinion to define and clarify her initial circulation.’ (Part 5, Chapter 7, The Role of Dissenting Opinions)

There are many times when an appellate court finds that a person ought to have a remedy, but the legislature has done nothing to change the law to enable this to happen. Sometimes judges have to take some step or speak out in that situation. But the essence of the common law is that change is brought about little by little. Sometimes, rather than make an immediate change, judges will signal the need for change at some undetermined time in the future. I think that is what Justice Ginsburg meant when she wrote of the Supreme Court occasionally stepping out in front of the political process but in other contexts placing path markers before finally confronting a major issue (Part 5, Chapter 4, The Madison lecture: Speaking in Judicial Voice, pp 244 to 247).

Justice Ginsburg wrote about progression in the law through a series of cases. Perhaps her approach had something to do with her famed love of opera. Complex cases absorb our attention utterly, we learn from them, but we know that with a loud rumbling they are decided and then gone, and the scene is changed. We move on to meet the challenge of another day, when we shall surely have to grapple with new cases. Maybe this is why Justice Ginsburg was such a fan of opera. Indeed, she even appeared in performances of operas.

Sitting in the study (as it were) we can hear the lectures that have been reprinted in the second half of the book. One example is A Decent Respect to the Opinions of [Human]Kind’, which discusses the benefit of the study of constitutional law on a comparative basis, that is, by considering the experience of other countries that have had to deal with similar constitutional issues.

Justice Ginsburg was very quietly spoken. That made all her listeners concentrate very hard on what she was saying. I vividly recall her concise, considered and penetrating comments and questions. She had one of the sharpest legal minds. She respected precedent, and used rational argument to reach her conclusions. She did not display any arrogance but remained considerate and humble. James Zirin wrote in the New York Post: ‘She gave us faith in the Court, which so often seeks to resolve our nation’s deepest controversies. She recognized the wisdom of Justice Robert Jackson who said of the Court, “we are not final because we are infallible, we are infallible only because we are final”.’

Overall, My Own Words is a revealing read. When the time came to put the book down and leave that study, I felt that I had shared some time in the presence of Justice Ginsburg and learnt more about her distinguished career and driving ideas, and also about the way the US Supreme Court works.

In 2015, Justice Ginsburg and Lady Hale wrote a joint Foreword for my own book, Common Law and Modern Society: Keeping pace with change. I was greatly honoured. The Foreword ends with the intriguing statement: that the book should encourage readers to play a useful part in shaping tomorrow’s law. The Foreword gives no clue as to who those readers might be. Nor does the Foreword say, as I had indicated in my book, that it is the task of the judiciary to keep the common law up to date. But I have no doubt that Justice Ginsburg was sympathetic to that approach.

Justice Ginsburg loved the law. She gave advice to young women, which is often quoted, encouraging them to become lawyers and aim for the bench. Justice Ginsburg supported the cause of women in many fields of life, and was sensitive to the gender dimensions of her judicial work. So her autobiography is obviously a perfect volume for a young woman lawyer, whatever her aspirations, but it is also a wonderful read for anyone who wants to know more about the Supreme Court of the United States.

Less well-known are Justice Ginsburg’s views about the professional obligations of legal practitioners. These may also be of interest to readers of Counsel. In a joint interview with Baroness Hale, immediate past President of the UK Supreme Court, arranged by Georgetown University in 2008 (which can be accessed on YouTube and is worth watching in full: bit.ly/32QHVvz), she explained her high expectations of legal practitioners. These followed her vision for the role of law and justice in society.

Her words were thoughtful and reflected her sense of purpose. They are worth remembering and quoting in our everyday lives, and so I end this appreciation of Justice Ginsburg by quoting them:

‘To me the highest obligation of someone in the legal profession is to recognise that you have training and talent… that equip you to make things a little better in your local community, your nation and your world, that is, to devote your talent not just to being the counterpart of an artisan or bricklayer who does a day’s work for a day’s pay but with someone who sees himself or herself as a true citizen of the community.’

© Lady Arden November 2020

My Own Words by Ruth Bader Ginsburg (with Mary Hartnett and Wendy W Williams)

Publisher: Simon & Schuster 2018

ISBN: 9781501145254

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar