*/

Judiciary

Queen’s Bench Division judges work extremely long hours, write lengthy judgments which enter the public arena, and are not always hearing cases which match the specialism they pursued at the Bar, Mr. Justice Tugendhat explained in his keynote address to the 5 Raymond Buildings Media and Entertainment Law Conference on 27 September. Nevertheless he encouraged practitioners to realise that ‘they may have a duty to the public to apply for appointment’.

His starting point was the need to find more judges to fill the gap created by lowering the retirement age to 70 while at the same time trying to deal with frequent requests from litigants to have their case assigned to a judge ‘with specialist experience and appropriate seniority’. As one of the judges tasked with deployment in the QBD, he weighed up the pros and cons of assigning a specialist judge to a case involving freedom of expression: on the one hand, specialist judges can take ‘twice or long or more’ to deal with cases, largely because they have to prep themselves on statutes and case law and counsel have to make submissions ‘which assume no knowledge on the part of the judge’; on the other hand, Queen’s Bench Division judges are required to be available for work across the whole Division and only spend a quarter of their time sitting in the QB list.

There are ‘very few specialist judges’ for freedom of expression cases and a problem with specialist judges overall. Due to the increasing ‘trend towards specialism in all areas of the law’ there are more specialist cases to be tried but ‘the judges appointed to the QBD include fewer who had more than one specialism in their professional practices’. ‘If the very few specialist judges decide all the cases, then criticisms that ought properly to be directed to the state of the law may become wrongly focussed on the person of individual judges’. In addition he finds it particularly important that ‘women judges should be amongst those judges who give judgments on issues of law which are socially and politically sensitive. That is the point of having a diverse judiciary’.

As for the work load, ‘High Court Judges in the QBD now commonly work for 50 to 60 hours per week during term time and they devote a significant part of the vacations to catching up with reserved judgments and other administrative work’. Last July he spent 19 of his 22 working days sitting, which included handing down reserved judgments and delivering ex tempore ones. ‘I regularly deliver judgments each week amounting on average to over 10,000 words or over 20 pages of text’. In July it was 50,000 words of judgment, which needed to be written or dictated—there is no one to assist in the drafting. In addition, there is all the pre-reading before a trial and ‘a pile of cases to decide on paper’, e.g. permission to appeal to the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal. He endorsed the Lord Chief Justice’s recent remark that the quality most required of a judge is fortitude.

Where are the specialist judges to come from in the future, he asked. ‘It is not for the judges to decide upon the future of the judiciary. It is for the public to express their views, for the JAC to conduct selection exercises and for the Government and parliament to decide on the applicable legislation’.

He appealed to all those present: ‘If you, or if people you know, are qualified to apply but decide not to apply, you should consider what the reasons are. And you should make known in public what those reasons are in general terms’.

His starting point was the need to find more judges to fill the gap created by lowering the retirement age to 70 while at the same time trying to deal with frequent requests from litigants to have their case assigned to a judge ‘with specialist experience and appropriate seniority’. As one of the judges tasked with deployment in the QBD, he weighed up the pros and cons of assigning a specialist judge to a case involving freedom of expression: on the one hand, specialist judges can take ‘twice or long or more’ to deal with cases, largely because they have to prep themselves on statutes and case law and counsel have to make submissions ‘which assume no knowledge on the part of the judge’; on the other hand, Queen’s Bench Division judges are required to be available for work across the whole Division and only spend a quarter of their time sitting in the QB list.

There are ‘very few specialist judges’ for freedom of expression cases and a problem with specialist judges overall. Due to the increasing ‘trend towards specialism in all areas of the law’ there are more specialist cases to be tried but ‘the judges appointed to the QBD include fewer who had more than one specialism in their professional practices’. ‘If the very few specialist judges decide all the cases, then criticisms that ought properly to be directed to the state of the law may become wrongly focussed on the person of individual judges’. In addition he finds it particularly important that ‘women judges should be amongst those judges who give judgments on issues of law which are socially and politically sensitive. That is the point of having a diverse judiciary’.

As for the work load, ‘High Court Judges in the QBD now commonly work for 50 to 60 hours per week during term time and they devote a significant part of the vacations to catching up with reserved judgments and other administrative work’. Last July he spent 19 of his 22 working days sitting, which included handing down reserved judgments and delivering ex tempore ones. ‘I regularly deliver judgments each week amounting on average to over 10,000 words or over 20 pages of text’. In July it was 50,000 words of judgment, which needed to be written or dictated—there is no one to assist in the drafting. In addition, there is all the pre-reading before a trial and ‘a pile of cases to decide on paper’, e.g. permission to appeal to the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal. He endorsed the Lord Chief Justice’s recent remark that the quality most required of a judge is fortitude.

Where are the specialist judges to come from in the future, he asked. ‘It is not for the judges to decide upon the future of the judiciary. It is for the public to express their views, for the JAC to conduct selection exercises and for the Government and parliament to decide on the applicable legislation’.

He appealed to all those present: ‘If you, or if people you know, are qualified to apply but decide not to apply, you should consider what the reasons are. And you should make known in public what those reasons are in general terms’.

Judiciary

Queen’s Bench Division judges work extremely long hours, write lengthy judgments which enter the public arena, and are not always hearing cases which match the specialism they pursued at the Bar, Mr. Justice Tugendhat explained in his keynote address to the 5 Raymond Buildings Media and Entertainment Law Conference on 27 September. Nevertheless he encouraged practitioners to realise that ‘they may have a duty to the public to apply for appointment’.

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

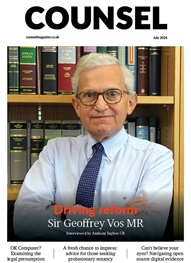

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts