*/

In May last year myself and some like-minded colleagues from underrepresented legal backgrounds put together a video to send out to schools, telling of our various routes to the Bar. Some, like me, were from ethnic minorities, while others were neurodiverse or grew up in deprived areas.

We tentatively came up with the tagline ‘The Law is Everybody’. I say tentatively because I, for one, was worried it might encourage the response, ‘Well, who says it isn’t?’ However, far from it. The tagline seemed to resonate with exactly the type of audience we were trying to encourage to see the Bar as a career for them. It was almost as if they had been looking in through the windows of an exclusive club that they never dreamed would accept them as a member and the mere statement that ‘The Law is Everybody’ seemed to give them the belief that they, too, could enter.

This reaction caused me to wonder why it is that even now, in 2023, some people, especially from non-White backgrounds, still feel they need ‘permission’ to enter top professions such as the law; still feel like they are standing on the outside looking in at opportunities that should be open to all.

One reason for this, in my view, is that history, or more accurately the way history has been recorded, has a role to play in this misperception. To quote US politician George Graham Vest, ‘History is written by the victors.’

Far from being an accurate record of events, history has often been written by the ‘victors’ in such a way as to emphasise certain roles while diminishing, or even excluding, the roles of others.

I experienced this as part of my campaign to get a permanent memorial to commemorate the 4,000 Caribbean servicemen, stationed at RAF Hunmanby Moor, near Filey, on the East Yorkshire coast during World War II. My Uncle Gilmour and Uncle Edwin were among 6,000 men from the Caribbean who voluntarily answered the call put out by the ‘Motherland’ and travelled over 4,000 miles to the UK, to help with the war effort.

Let us not forget that by June 1940, Britain was in a truly perilous position. France had surrendered in May and Hitler was just 26 miles away across the Channel. The Americans were not to enter the war until the bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941. Britain was therefore in dire straits and there can be absolutely no doubt that the volunteers from the Caribbean played a vital role in turning the course of the war in favour of Great Britain and its allies.

Marshal of the Royal Air Force William Sholto Douglas, 1st Baron Douglas of Kirtleside, said in 1942: ‘You rallied promptly to our side and the cause for which we stood, determined with us to defeat those powers which would destroy civilisation and plunge the world into barbarism.’

Many of those who came were teenagers. Some may even have lied about their age and were perhaps not old enough to serve, but they came nonetheless. They came because the Motherland was in need. They came and they were proud to do so. Many lost their lives and never returned.

However, after the war, their selfless acts of bravery and sacrifice were almost completely erased from the history books. Many were denied their medals and some had to wait over eight decades before they were finally awarded what they had rightfully earned.* These men and their courageous deeds became invisible in that great story of those who fought for the rights and freedoms that we all enjoy in this country today.

There is a school of thought that this was done deliberately by the government of the day, to avoid the men going back to their islands as heroes and then feeling emboldened to petition for independence.** History was therefore manipulated to create a false narrative that mass immigration from the Caribbean started with the arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948. The truth is that thousands of people of colour had come to these shores nearly a decade earlier, as a major part of the war effort.

The net effect of this has been to completely omit the bravery and sacrifice of Caribbean solders and leave them standing on the outside of one of history’s greatest triumphs when, in truth, they were a vital component. This has culminated in a situation where, today, there are people both young and old who simply have no idea that people of colour fought and died alongside their Bristish counterparts in both World Wars.

Having discovered the hidden history of the 4,000 servicemen from the Caribbean and my family’s connection to it, I contacted Filey Council, confidently expecting it to have archives stuffed with photographs and streets lined with memorials and statues, but there was absolutely nothing! Nothing in the local museum either. Indeed, when I visited Filey, a small seaside resort with a population of just over 6,000 souls, nobody that I asked knew anything about it.

I then approached the council and offered to raise funds to pay for a plaque to commemorate the service of the men from the Caribbean, which could be placed in the Memorial Gardens. To my astonishment, not only was I told that the council didn’t want a plaque, but also that the Memorial Gardens were only for the remembrance of people from Filey, (I wish I was joking).*** Yet another example of people of colour being left in the margins of history, on the outside looking in, but not feeling welcome to enter.

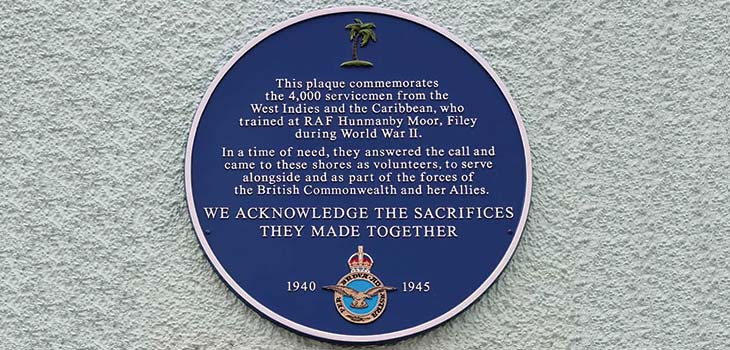

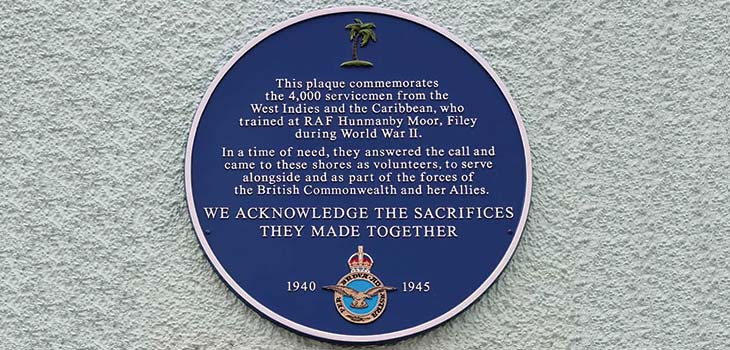

Fast forward three years and I am delighted to say that after a long campaign, on 1 April 2023 (the 105th Birthday of the RAF,) a plaque was unveiled to the 4,000 Caribbean servicemen. Not in the Memorial Gardens, but on the house of a Filey resident who, like many from the town, fully embraced our campaign and wanted to make it clear that this part of Caribbean history was also part of their history.

The event was a truly joyous occasion attended by over 200 people and six of the original Caribbean veterans, whose ages ranged from 96-99. Unbelievably, however, Filey Council is still maintaining its position that the Caribbean contingent cannot be commemorated by a plaque in the Memorial Gardens.

This is why accurately recording history is critical to changing attitudes today. Perhaps if some people were better informed as to the extent of our shared histories, then there might be less racism and marginalising of ethnic minorities.

I also hope that, just as we now say ‘The Law is Everybody’, one day Filey Council will realise that the ‘War is Everybody’ too, especially all those who contributed to the victories!

RAF Warrant Officer Donald Campbell (retr’d), veterans Alford Gardner and ‘Jakey’ Jacobs with RAF Warrant Officer Kenneth Straun (retr’d).

* 'WW2 RAF veteran from Knowle finally receives medals', BBC News, 15 February 2023

**‘The Black British soldiers who were deliberately forgotten’, Imperial War Museum Stories

*** ‘Filey memorial for Caribbean WWII RAF ground crew to go ahead’, BBC News, 6 January 2023

Windrush 75: 2023 sees the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain on 22 June 1948: www.windrush75.org

Law is Everybody – the North Eastern Circuit Diversity & Equality Feature Film can be viewed here.

In May last year myself and some like-minded colleagues from underrepresented legal backgrounds put together a video to send out to schools, telling of our various routes to the Bar. Some, like me, were from ethnic minorities, while others were neurodiverse or grew up in deprived areas.

We tentatively came up with the tagline ‘The Law is Everybody’. I say tentatively because I, for one, was worried it might encourage the response, ‘Well, who says it isn’t?’ However, far from it. The tagline seemed to resonate with exactly the type of audience we were trying to encourage to see the Bar as a career for them. It was almost as if they had been looking in through the windows of an exclusive club that they never dreamed would accept them as a member and the mere statement that ‘The Law is Everybody’ seemed to give them the belief that they, too, could enter.

This reaction caused me to wonder why it is that even now, in 2023, some people, especially from non-White backgrounds, still feel they need ‘permission’ to enter top professions such as the law; still feel like they are standing on the outside looking in at opportunities that should be open to all.

One reason for this, in my view, is that history, or more accurately the way history has been recorded, has a role to play in this misperception. To quote US politician George Graham Vest, ‘History is written by the victors.’

Far from being an accurate record of events, history has often been written by the ‘victors’ in such a way as to emphasise certain roles while diminishing, or even excluding, the roles of others.

I experienced this as part of my campaign to get a permanent memorial to commemorate the 4,000 Caribbean servicemen, stationed at RAF Hunmanby Moor, near Filey, on the East Yorkshire coast during World War II. My Uncle Gilmour and Uncle Edwin were among 6,000 men from the Caribbean who voluntarily answered the call put out by the ‘Motherland’ and travelled over 4,000 miles to the UK, to help with the war effort.

Let us not forget that by June 1940, Britain was in a truly perilous position. France had surrendered in May and Hitler was just 26 miles away across the Channel. The Americans were not to enter the war until the bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941. Britain was therefore in dire straits and there can be absolutely no doubt that the volunteers from the Caribbean played a vital role in turning the course of the war in favour of Great Britain and its allies.

Marshal of the Royal Air Force William Sholto Douglas, 1st Baron Douglas of Kirtleside, said in 1942: ‘You rallied promptly to our side and the cause for which we stood, determined with us to defeat those powers which would destroy civilisation and plunge the world into barbarism.’

Many of those who came were teenagers. Some may even have lied about their age and were perhaps not old enough to serve, but they came nonetheless. They came because the Motherland was in need. They came and they were proud to do so. Many lost their lives and never returned.

However, after the war, their selfless acts of bravery and sacrifice were almost completely erased from the history books. Many were denied their medals and some had to wait over eight decades before they were finally awarded what they had rightfully earned.* These men and their courageous deeds became invisible in that great story of those who fought for the rights and freedoms that we all enjoy in this country today.

There is a school of thought that this was done deliberately by the government of the day, to avoid the men going back to their islands as heroes and then feeling emboldened to petition for independence.** History was therefore manipulated to create a false narrative that mass immigration from the Caribbean started with the arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948. The truth is that thousands of people of colour had come to these shores nearly a decade earlier, as a major part of the war effort.

The net effect of this has been to completely omit the bravery and sacrifice of Caribbean solders and leave them standing on the outside of one of history’s greatest triumphs when, in truth, they were a vital component. This has culminated in a situation where, today, there are people both young and old who simply have no idea that people of colour fought and died alongside their Bristish counterparts in both World Wars.

Having discovered the hidden history of the 4,000 servicemen from the Caribbean and my family’s connection to it, I contacted Filey Council, confidently expecting it to have archives stuffed with photographs and streets lined with memorials and statues, but there was absolutely nothing! Nothing in the local museum either. Indeed, when I visited Filey, a small seaside resort with a population of just over 6,000 souls, nobody that I asked knew anything about it.

I then approached the council and offered to raise funds to pay for a plaque to commemorate the service of the men from the Caribbean, which could be placed in the Memorial Gardens. To my astonishment, not only was I told that the council didn’t want a plaque, but also that the Memorial Gardens were only for the remembrance of people from Filey, (I wish I was joking).*** Yet another example of people of colour being left in the margins of history, on the outside looking in, but not feeling welcome to enter.

Fast forward three years and I am delighted to say that after a long campaign, on 1 April 2023 (the 105th Birthday of the RAF,) a plaque was unveiled to the 4,000 Caribbean servicemen. Not in the Memorial Gardens, but on the house of a Filey resident who, like many from the town, fully embraced our campaign and wanted to make it clear that this part of Caribbean history was also part of their history.

The event was a truly joyous occasion attended by over 200 people and six of the original Caribbean veterans, whose ages ranged from 96-99. Unbelievably, however, Filey Council is still maintaining its position that the Caribbean contingent cannot be commemorated by a plaque in the Memorial Gardens.

This is why accurately recording history is critical to changing attitudes today. Perhaps if some people were better informed as to the extent of our shared histories, then there might be less racism and marginalising of ethnic minorities.

I also hope that, just as we now say ‘The Law is Everybody’, one day Filey Council will realise that the ‘War is Everybody’ too, especially all those who contributed to the victories!

RAF Warrant Officer Donald Campbell (retr’d), veterans Alford Gardner and ‘Jakey’ Jacobs with RAF Warrant Officer Kenneth Straun (retr’d).

* 'WW2 RAF veteran from Knowle finally receives medals', BBC News, 15 February 2023

**‘The Black British soldiers who were deliberately forgotten’, Imperial War Museum Stories

*** ‘Filey memorial for Caribbean WWII RAF ground crew to go ahead’, BBC News, 6 January 2023

Windrush 75: 2023 sees the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain on 22 June 1948: www.windrush75.org

Law is Everybody – the North Eastern Circuit Diversity & Equality Feature Film can be viewed here.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar