*/

Franz Kafka is like an enveloping spirit in Prague. He is everywhere. There is a rather modernist statue of him in the Jewish Quarter. His silhouette adorns mugs and T-shirts in every tatty tourist shop. There is an overly expensive (and rather uninformative) Kafka Museum and a bookshop in his name. And, above all else, there is his house: a miniscule artisans’ cottage found down Golden Lane inside the grounds of the city’s castle.

Part of my adoration for Kafka comes from a lawyer’s training but also from the impromptu descriptor expressed in many a legal case: ‘a Kafkaesque situation’. Why? The sense of the expression in a legal context is a situation of labyrinthian complexity, absurdity, perversity where the law is traduced by procedure and injustice and is, to use the proverbial expression, ‘an ass’.

Kafka did, of course, train as a lawyer, though he did not find it a particularly pleasant experience. According to one account cited by the legal scholar Professor Robin West, he found that the study of law ‘had the intellectual excitement of chewing sawdust that had been pre-chewed by thousands of other mouths’. West, in her philosophical monograph, argues that Kafka’s world presents law as alienating and excessively authoritarian, exerting in people a craving for conformity: ‘Kafka’s world is populated by excessively authoritarian personalities. Kafka’s characters usually do what they do – go to work in the morning, become lovers, commit crimes, obey laws, or whatever – not because they believe that by doing so, they will improve their own wellbeing but because they have been told to do so and crave being told to do so.’ (R West, ‘Autonomy, and Choice: The Role of Consent in the Moral and Political Visions of Franz Kafka and Richard Posner’ (2011) 99 Harvard Law Review 384.)

This submission to authority pervades Kafka’s short stories and parables. His most dramatic example is to be found in The Trial, written between 1914 and 1915, published posthumously in 1925 and immortalised in Orson Welles’ 1962 film.

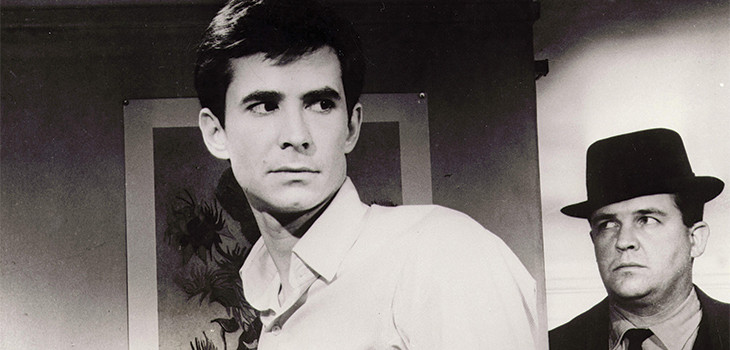

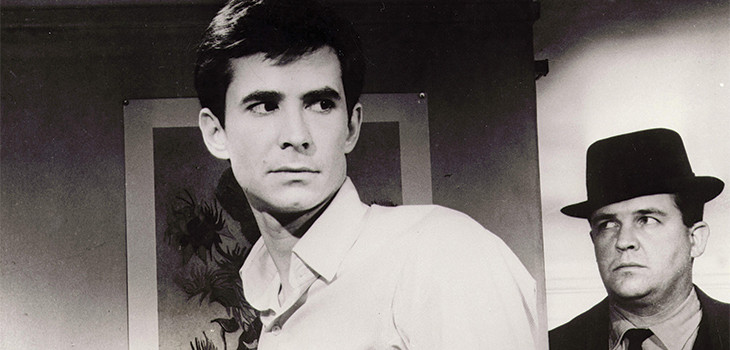

Many of us will be familiar with the plot. Bureaucrat Josef K (Anthony Perkins, a good Kafka likeness) is arrested without having ever done anything wrong. He never learns the nature of the charges against him. He is arrested but not imprisoned; interrogated but never forced to appear. He rails against the system and endeavours to find out the charges against him but, in time, he passively accepts the jurisdiction of the court (with its secret signs) and the law’s authority, which results ultimately in his own death sentence.

Welles takes the role of Josef K’s unhelpful lawyer, Albert Hastler, known as The Advocate, who spends much of his time in bed, smoking cigars, attended to by his mistress (Romy Schneider).

Kafka’s parable The Problem of our Laws informs us that law is ultimately sustained, not by force, but by the craving of the governed for judgement by lawful, noble authority. It is this human craving, even more than the urge of the powerful to dominate, that sustains the illusion of certainty, fairness, generality, and justice. Presciently, Welles, in a pre-film monologue to The Trial, recites a similar short story of Kafka’s about over compliance, Before the Laws, set to pinscreen animation by artist Alexandre Alexeieff.

Welles himself was also obsessed by the law. He played Hank Quinlan, the corrupt framing cop in his masterpiece Touch of Evil (1958). He played Clarence Darrow in Compulsion (1959), a dramatisation of the Leopold and Lowe case based on coercive and abusive wealth and age-based relationships – relevant to our current focus on coercive behaviour and, indeed, the imposition of control by the increasingly narrow plutocracy that COVID has accentuated.

A sidenote: Welles arrived in Ireland as a 15-year-old farm boy, precocious and overweight beyond his years. After a tour of the West Coast, a kind of obligatory rite of passage, he was penniless. Clutching fake representations and reviews he presented himself before Mr Michael McLiammor at The Gate Theatre in Dublin and said ‘I am a prominent Broadway actor.’ McLiammor did not believe a word of it but gave him a job. Old Ireland. He was impressive. An impressive confidence trickster. The point of odd coincidence in my life is that Welles went back to The Gate often and I met him once. It was an extraordinary experience to be in the presence of that level of lifestyle excess and utter egotism and, let us face it, genius.

The Trial with Anthony Perkins is, then, a reasonably faithful adaption of the text and a perfect evocation of the shadows and fog of Prague in a noirish sense. Welles spent six months writing the screenplay. Steven Soderbergh’s 1991 film with Jeremy Irons is less compelling and not imbued with brilliance. In fact, some consider Welles’ adaptation, including the great man himself, to be his greatest film. But to my mind, that is like asking, ‘Which is the greatest play by Shakespeare?’

Ultimately, the film is a sage warning for our age about over compliance and misplaced trust in authority. Other Kafka novel adaptations fall short but those of The Castle, his other great novel, depict well the dangers of arbitrary authority and remind lawyers to be acutely conscious of the frustrations of state bureaucracy. Indeed, Kafka accurately predicted the difficulties we must all deal with now in this technocratic age. Faith in due process and legal fairness is one of the few values left to clutch onto. Kafka, however, provides a stern warning about the limits of faith and consent to legal authority.

So, what lessons should we, as lawyers, take from the film? Never unconditionally comply with the edicts of authority. Do not obey orders just because they are orders. Be critical and circumspect and conscious of ethical criteria about instructions. Exercise judgement. Be independent if one can. The Trial and Kafka’s other texts are thus hugely relevant to our age.

Franz Kafka is like an enveloping spirit in Prague. He is everywhere. There is a rather modernist statue of him in the Jewish Quarter. His silhouette adorns mugs and T-shirts in every tatty tourist shop. There is an overly expensive (and rather uninformative) Kafka Museum and a bookshop in his name. And, above all else, there is his house: a miniscule artisans’ cottage found down Golden Lane inside the grounds of the city’s castle.

Part of my adoration for Kafka comes from a lawyer’s training but also from the impromptu descriptor expressed in many a legal case: ‘a Kafkaesque situation’. Why? The sense of the expression in a legal context is a situation of labyrinthian complexity, absurdity, perversity where the law is traduced by procedure and injustice and is, to use the proverbial expression, ‘an ass’.

Kafka did, of course, train as a lawyer, though he did not find it a particularly pleasant experience. According to one account cited by the legal scholar Professor Robin West, he found that the study of law ‘had the intellectual excitement of chewing sawdust that had been pre-chewed by thousands of other mouths’. West, in her philosophical monograph, argues that Kafka’s world presents law as alienating and excessively authoritarian, exerting in people a craving for conformity: ‘Kafka’s world is populated by excessively authoritarian personalities. Kafka’s characters usually do what they do – go to work in the morning, become lovers, commit crimes, obey laws, or whatever – not because they believe that by doing so, they will improve their own wellbeing but because they have been told to do so and crave being told to do so.’ (R West, ‘Autonomy, and Choice: The Role of Consent in the Moral and Political Visions of Franz Kafka and Richard Posner’ (2011) 99 Harvard Law Review 384.)

This submission to authority pervades Kafka’s short stories and parables. His most dramatic example is to be found in The Trial, written between 1914 and 1915, published posthumously in 1925 and immortalised in Orson Welles’ 1962 film.

Many of us will be familiar with the plot. Bureaucrat Josef K (Anthony Perkins, a good Kafka likeness) is arrested without having ever done anything wrong. He never learns the nature of the charges against him. He is arrested but not imprisoned; interrogated but never forced to appear. He rails against the system and endeavours to find out the charges against him but, in time, he passively accepts the jurisdiction of the court (with its secret signs) and the law’s authority, which results ultimately in his own death sentence.

Welles takes the role of Josef K’s unhelpful lawyer, Albert Hastler, known as The Advocate, who spends much of his time in bed, smoking cigars, attended to by his mistress (Romy Schneider).

Kafka’s parable The Problem of our Laws informs us that law is ultimately sustained, not by force, but by the craving of the governed for judgement by lawful, noble authority. It is this human craving, even more than the urge of the powerful to dominate, that sustains the illusion of certainty, fairness, generality, and justice. Presciently, Welles, in a pre-film monologue to The Trial, recites a similar short story of Kafka’s about over compliance, Before the Laws, set to pinscreen animation by artist Alexandre Alexeieff.

Welles himself was also obsessed by the law. He played Hank Quinlan, the corrupt framing cop in his masterpiece Touch of Evil (1958). He played Clarence Darrow in Compulsion (1959), a dramatisation of the Leopold and Lowe case based on coercive and abusive wealth and age-based relationships – relevant to our current focus on coercive behaviour and, indeed, the imposition of control by the increasingly narrow plutocracy that COVID has accentuated.

A sidenote: Welles arrived in Ireland as a 15-year-old farm boy, precocious and overweight beyond his years. After a tour of the West Coast, a kind of obligatory rite of passage, he was penniless. Clutching fake representations and reviews he presented himself before Mr Michael McLiammor at The Gate Theatre in Dublin and said ‘I am a prominent Broadway actor.’ McLiammor did not believe a word of it but gave him a job. Old Ireland. He was impressive. An impressive confidence trickster. The point of odd coincidence in my life is that Welles went back to The Gate often and I met him once. It was an extraordinary experience to be in the presence of that level of lifestyle excess and utter egotism and, let us face it, genius.

The Trial with Anthony Perkins is, then, a reasonably faithful adaption of the text and a perfect evocation of the shadows and fog of Prague in a noirish sense. Welles spent six months writing the screenplay. Steven Soderbergh’s 1991 film with Jeremy Irons is less compelling and not imbued with brilliance. In fact, some consider Welles’ adaptation, including the great man himself, to be his greatest film. But to my mind, that is like asking, ‘Which is the greatest play by Shakespeare?’

Ultimately, the film is a sage warning for our age about over compliance and misplaced trust in authority. Other Kafka novel adaptations fall short but those of The Castle, his other great novel, depict well the dangers of arbitrary authority and remind lawyers to be acutely conscious of the frustrations of state bureaucracy. Indeed, Kafka accurately predicted the difficulties we must all deal with now in this technocratic age. Faith in due process and legal fairness is one of the few values left to clutch onto. Kafka, however, provides a stern warning about the limits of faith and consent to legal authority.

So, what lessons should we, as lawyers, take from the film? Never unconditionally comply with the edicts of authority. Do not obey orders just because they are orders. Be critical and circumspect and conscious of ethical criteria about instructions. Exercise judgement. Be independent if one can. The Trial and Kafka’s other texts are thus hugely relevant to our age.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar