*/

Relevant to current times, Aki Kaurismaki’s very human story focuses on the plight of the refugee and responsibility of the law, writes David Langwallner

I was hungry and you gave me food. I was thirsty and you gave me drink. I was a stranger and you welcomed me.

Matthew 25:35

Finnish filmmaker Aki Kaurismaki is an international treasure and one of the last humanist film directors (in the good company of the great Japanese director Hirokazu Koreeda (I Wish: 2011) who himself is up there with Yasujiro Ozu – the highest compliment!)

Kaurismaki’s subject is always the human. The individual. The person. Like the exploited Match Factory Girl (1990) working in Lowry-like conditions, his films concern human predicaments experienced by those of limited choice. Like those on the boats. Coming to the UK.

Kaurismaki is, in fact, a great miniaturist artist. No great political statements. For him, it is the little people who matter; just like L S Lowry’s matchstick figures and cats and dogs, Pierre Bonnard’s family scenes and Pieter Bruegel’s peasant wedding.

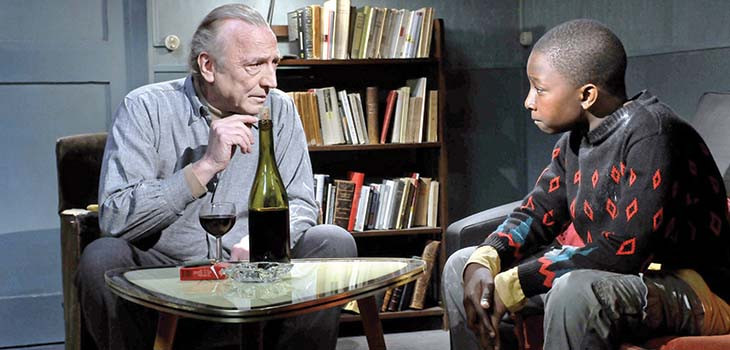

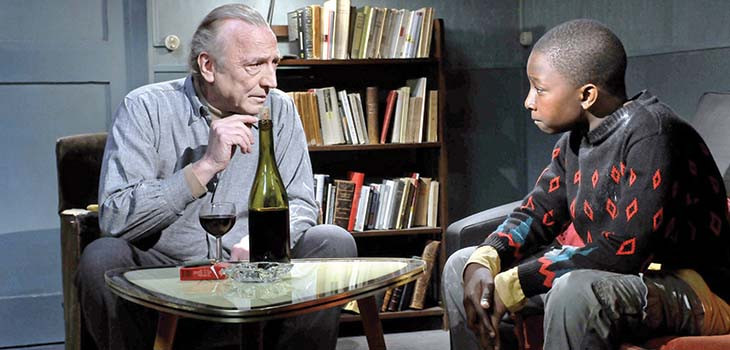

In Le Havre (2011), it is the migrant. Idrissa (Blondin Miguel) is a young African immigrant child who arrives by cargo ship. He finds himself alone and lost in that city of ambiguity, a border crossing, a half-state, a waiting house, a weigh station. The film has awful scenes of the way French detention centres, such as the notorious Sangatte, worked. I would question whether the detention centres near Heathrow, where I have represented, are that much more civilised in recent times.

The young migrant is befriended by Marcel Marx (André Wilms), a dissolute middle-aged man who, having given up on his literary ambitions, enjoys too much wine and makes his money shining shoes in the streets. At one level, it is a rustic idyll though how practicable it is difficult to work out.

Marcel goes home every evening to Arletty (Kati Outinen), his loving, too indulgent, wife. In conventional terms, he is a failure, but he is a kind man who puts his reputation on the line in order to protect Idrissa at the risk of prosecution by the gendarmes and the local prosecutor. Bureaucratic officiousness looms large and sinister but is also charitable; a kind of reverse of the prosecutor in Camus’ The Outsider.

Marcel finds out that Arletty is dying of cancer – not the decadent bon viveur that he is, but her, which leads to a crisis of conscience. Why her and not him? He is madly in love with his wife and helpless without her. [Spoiler alert: all ends well in the bittersweet Kaurismaki universe. The diagnosis was wrong and she is saved, and so is Idrissa.]

Le Havre, of course, is a response not just to Finnish immigration policies but a form of dehumanisation that Kaurismaki perceives everywhere, just as HG Wells saw presciently a world devastated by economic disaster and plague – though what is cause and effect is difficult to disentangle in these times. Now Mr Johnson and Ms Patel have cut a deal with the deeply ambiguous Mr Kawage, President of Rwanda to send refugees to his land of peace and tranquillity. Economic migration determined by whom? Has the world become science fiction? Not when fiction is reality.

Back to the film – a masterpiece crowned ‘best international film’ at the 2011 Munich International Film Festival among other awards. For us lawyers, especially those representing in immigration and asylum cases, it resonates deeply and underscores the need to protect those subject to international legal and regulatory regimes which at times approach levels of absurdity. Judges in immigration courts are doing their absolute best, no doubt, in awful times but are constrained by an incomprehensible, in human terms, set of rules. Well, Kaurismaki cares. He reminds us that humanity is all important and that often nonsense reports by state authorities should be treated with utmost scepticism. I defy any lawyer to watch this film and not be moved about the responsibility of the profession.

I was hungry and you gave me food. I was thirsty and you gave me drink. I was a stranger and you welcomed me.

Matthew 25:35

Finnish filmmaker Aki Kaurismaki is an international treasure and one of the last humanist film directors (in the good company of the great Japanese director Hirokazu Koreeda (I Wish: 2011) who himself is up there with Yasujiro Ozu – the highest compliment!)

Kaurismaki’s subject is always the human. The individual. The person. Like the exploited Match Factory Girl (1990) working in Lowry-like conditions, his films concern human predicaments experienced by those of limited choice. Like those on the boats. Coming to the UK.

Kaurismaki is, in fact, a great miniaturist artist. No great political statements. For him, it is the little people who matter; just like L S Lowry’s matchstick figures and cats and dogs, Pierre Bonnard’s family scenes and Pieter Bruegel’s peasant wedding.

In Le Havre (2011), it is the migrant. Idrissa (Blondin Miguel) is a young African immigrant child who arrives by cargo ship. He finds himself alone and lost in that city of ambiguity, a border crossing, a half-state, a waiting house, a weigh station. The film has awful scenes of the way French detention centres, such as the notorious Sangatte, worked. I would question whether the detention centres near Heathrow, where I have represented, are that much more civilised in recent times.

The young migrant is befriended by Marcel Marx (André Wilms), a dissolute middle-aged man who, having given up on his literary ambitions, enjoys too much wine and makes his money shining shoes in the streets. At one level, it is a rustic idyll though how practicable it is difficult to work out.

Marcel goes home every evening to Arletty (Kati Outinen), his loving, too indulgent, wife. In conventional terms, he is a failure, but he is a kind man who puts his reputation on the line in order to protect Idrissa at the risk of prosecution by the gendarmes and the local prosecutor. Bureaucratic officiousness looms large and sinister but is also charitable; a kind of reverse of the prosecutor in Camus’ The Outsider.

Marcel finds out that Arletty is dying of cancer – not the decadent bon viveur that he is, but her, which leads to a crisis of conscience. Why her and not him? He is madly in love with his wife and helpless without her. [Spoiler alert: all ends well in the bittersweet Kaurismaki universe. The diagnosis was wrong and she is saved, and so is Idrissa.]

Le Havre, of course, is a response not just to Finnish immigration policies but a form of dehumanisation that Kaurismaki perceives everywhere, just as HG Wells saw presciently a world devastated by economic disaster and plague – though what is cause and effect is difficult to disentangle in these times. Now Mr Johnson and Ms Patel have cut a deal with the deeply ambiguous Mr Kawage, President of Rwanda to send refugees to his land of peace and tranquillity. Economic migration determined by whom? Has the world become science fiction? Not when fiction is reality.

Back to the film – a masterpiece crowned ‘best international film’ at the 2011 Munich International Film Festival among other awards. For us lawyers, especially those representing in immigration and asylum cases, it resonates deeply and underscores the need to protect those subject to international legal and regulatory regimes which at times approach levels of absurdity. Judges in immigration courts are doing their absolute best, no doubt, in awful times but are constrained by an incomprehensible, in human terms, set of rules. Well, Kaurismaki cares. He reminds us that humanity is all important and that often nonsense reports by state authorities should be treated with utmost scepticism. I defy any lawyer to watch this film and not be moved about the responsibility of the profession.

Relevant to current times, Aki Kaurismaki’s very human story focuses on the plight of the refugee and responsibility of the law, writes David Langwallner

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar