*/

Just as there are different sorts of lawyers, namely solicitor, barrister, practising and non-practising, the lawyer who goes into accountancy or business or journalism or public administration, and academia, there are different types of lawyer-politician. There is the lawyer who sets out to be a professional lawyer, and somehow accidentally gets drawn into politics; and the lawyer who sets out to be a professional lawyer only insofar as this serves as an intentional or hopeful stepping-stone to politics.

When we debate who was the finest orator of all time, we think of Cicero and Demosthenes. When Cicero, a sort of Roman lawyer, spoke, the people said: ‘What a marvellous speaker!’ When Demosthenes spoke, a sort of Greek politician, the people said: ‘Let’s march!’ The winner was clear.

Lawyers, however, undoubtedly bring strengths to the office of PM. They are the power of analysis, relevance, logic, order, argument, advocacy, oratory, persuasion, balance and judgement. As a skilled negotiator they can promote peace. As a dynamic character they can give leadership in war. However, there can be damaging weaknesses. They may be, or at least seen to be, dull, boring, balanced, pedantic, petty, too intellectual, too clever, too much concerned with procedure and detail, perhaps lacking in leadership, charisma, passion. Asquith, for example, was first rate in peace time, a failure in war. Lloyd George was highly controversial in peace time, but a huge success in war.

And before the advent of the office of PM as we know it today, the Sovereign had the equivalent, namely the Lord Chancellor or the First Secretary. Thomas Beckett, a canon lawyer, enraged Henry II in 1170 by insisting upon the legal rights of the church, with unfortunate consequences. Thomas Cromwell, Gray’s Inn, made an error of judgement in selecting Anne of Cleves as a wife for Henry VIII and fell out of royal favour 1540 (a capital offence at the time). The Cecils, father and son, William Cecil, Lord Burghley and Robert Cecil, both of Gray’s Inn, were lawyers and highly successful principal ministers to Elizabeth I.

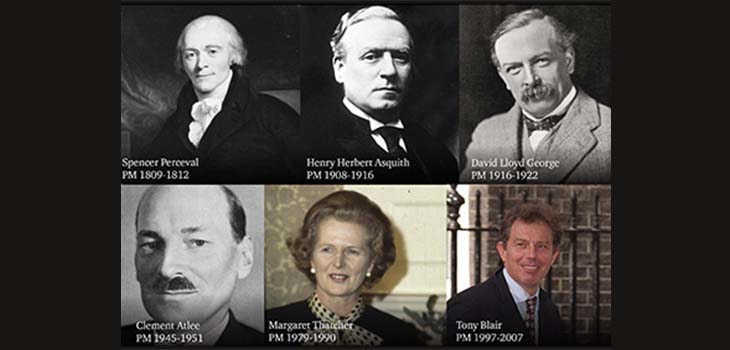

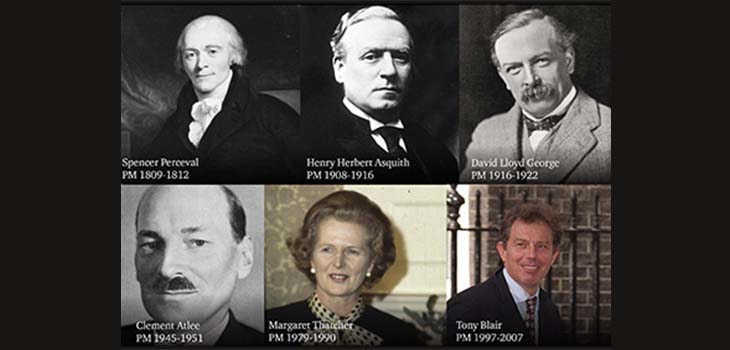

So, the candidates for consideration since Walpole became the first PM in 1721, ie in modern times, appear to be: Spencer Perceval, Henry Herbert Asquith, David Lloyd George, Clement Atlee, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. Sir Keir Starmer, Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition, appears at the moment to be the only openly aspiring lawyer PM.

Spencer Perceval (PM 1809-1812) was a professional barrister of some standing. He was a son of the Earl of Egmont though he had to make his own way. He was a good debater, quick on his feet, displaying typical advocate skills. He was described as able, trustworthy and narrow-minded. Most unfortunately a deranged individual, Bellingham, who claimed to have received no compensation from the government in respect of an unpaid debt in Russia, entered the Parliament building and assassinated Perceval.

A large number of PMs have been members of an Inn of Court, but as honorary members. For example, Lord Sidmouth, Lord Grenville, George Canning, Lord Goderich, Lord Melbourne, Sir Robert Peel, Disraeli, Gladstone, Lord Salisbury and Neville Chamberlain were all Lincoln’s Inn; and Winston Churchill and Edward Heath were Gray’s Inn; and Eden, Macmillan, Major and Cameron Middle Temple; and Callaghan Inner Temple.

Herbert Henry Asquith, born 1852, was PM from 1908-1916. He excelled as an undergraduate in classics at Oxford, was called to the Bar by Lincoln’s Inn and practised at the Bar, with some success, though did not take silk. He was drawn into politics, aged 34, and soon excelled in public office under PM Gladstone. Asquith was the perfect peace-time PM. But he proved unequal to the task of leading the country in World War I, and was forced to resign in 1916, never able to inspire the nation.

David Lloyd George, born 1863 in Wales, qualified as a solicitor as a young man and engaged in small-time practice in North Wales. But he had political ambitions from the start; MP in 1890 aged 27. He was bilingual Welsh and English, and a truly fine speaker. Many said that from experience he had developed the pulpit manner. He clearly had high political aspirations, right from the beginning. In office from 1905 he soon dominated the House of Commons, and brought in old age pensions and curbed the powers of the House of Lords. In WWI he organised the production of munitions in 1915 and 1916-1918 he led the nation to victory. Unfortunately, the negotiated peace in the Treaty of Versailles was not a success, nor was his peace-time premiership.

Clement Atlee, born 1883, was a somewhat shy seemingly unambitious man, called to the Bar by Inner Temple in 1906 aged 23. He practised for a few years, but without much enthusiasm. Charitable work in the East End of London suited him better. Wounded in WWI, he never returned to the Bar. His political career was largely governed by chance. The Labour Party leadership fell vacant in 1935, and he became Leader. Deputy PM in 1940 in Winston Churchill’s coalition government, Atlee went on to win a landslide political victory at the end of the war in 1945. He was easily underestimated. He kept control of a cabinet of egotistical men; he wasted no words; he developed a quiet but highly effective leadership; he carried through a vast legislative programme.

Margaret Thatcher, born 1925, came from a modest middle class Methodist background, read Chemistry at Oxford, and started work as a research chemist. By age 24 she was a parliamentary candidate, trying several times, ultimately elected 1959 aged 34. Meanwhile she qualified as a barrister, Lincoln’s Inn, specialising in tax. As Leader of the Opposition, always a powerful opponent. In office 11½ years, ultimately she achieved the Order of Merit and the Garter, and was given a virtual state funeral, equalled only by Winston Churchill. Her law stood her in very good stead.

Tony Blair read law at Oxford, was called by Lincoln’s, started as a pupil in the chambers of Derry Irvine (a leading Labour activist), married a fellow pupil in the same chambers, and seemed well set for a legal career. But aged 29 he was seeking a parliamentary seat, aged 30 he had one, and by 41 he was the Leader of the Labour Party. By 44 he was PM (and appointed Derry Irvine as Lord Chancellor). His three successful general elections, his ten years in office, and some political achievements, were clouded by the general perception (after the event) that his involvement in the Iraq was a serious mistake. As a lawyer could he or should he have avoided that mistake?

Asquith, Lloyd George, Atlee, Thatcher and Blair all showed themselves in their early years to be capable lawyers. But all set their minds on a political career, and all brought their legal skills, along with other skills, to bear upon generally successful careers as PM.

Sir Keir Starmer – the only openly aspiring lawyer-PM today

Just as there are different sorts of lawyers, namely solicitor, barrister, practising and non-practising, the lawyer who goes into accountancy or business or journalism or public administration, and academia, there are different types of lawyer-politician. There is the lawyer who sets out to be a professional lawyer, and somehow accidentally gets drawn into politics; and the lawyer who sets out to be a professional lawyer only insofar as this serves as an intentional or hopeful stepping-stone to politics.

When we debate who was the finest orator of all time, we think of Cicero and Demosthenes. When Cicero, a sort of Roman lawyer, spoke, the people said: ‘What a marvellous speaker!’ When Demosthenes spoke, a sort of Greek politician, the people said: ‘Let’s march!’ The winner was clear.

Lawyers, however, undoubtedly bring strengths to the office of PM. They are the power of analysis, relevance, logic, order, argument, advocacy, oratory, persuasion, balance and judgement. As a skilled negotiator they can promote peace. As a dynamic character they can give leadership in war. However, there can be damaging weaknesses. They may be, or at least seen to be, dull, boring, balanced, pedantic, petty, too intellectual, too clever, too much concerned with procedure and detail, perhaps lacking in leadership, charisma, passion. Asquith, for example, was first rate in peace time, a failure in war. Lloyd George was highly controversial in peace time, but a huge success in war.

And before the advent of the office of PM as we know it today, the Sovereign had the equivalent, namely the Lord Chancellor or the First Secretary. Thomas Beckett, a canon lawyer, enraged Henry II in 1170 by insisting upon the legal rights of the church, with unfortunate consequences. Thomas Cromwell, Gray’s Inn, made an error of judgement in selecting Anne of Cleves as a wife for Henry VIII and fell out of royal favour 1540 (a capital offence at the time). The Cecils, father and son, William Cecil, Lord Burghley and Robert Cecil, both of Gray’s Inn, were lawyers and highly successful principal ministers to Elizabeth I.

So, the candidates for consideration since Walpole became the first PM in 1721, ie in modern times, appear to be: Spencer Perceval, Henry Herbert Asquith, David Lloyd George, Clement Atlee, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. Sir Keir Starmer, Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition, appears at the moment to be the only openly aspiring lawyer PM.

Spencer Perceval (PM 1809-1812) was a professional barrister of some standing. He was a son of the Earl of Egmont though he had to make his own way. He was a good debater, quick on his feet, displaying typical advocate skills. He was described as able, trustworthy and narrow-minded. Most unfortunately a deranged individual, Bellingham, who claimed to have received no compensation from the government in respect of an unpaid debt in Russia, entered the Parliament building and assassinated Perceval.

A large number of PMs have been members of an Inn of Court, but as honorary members. For example, Lord Sidmouth, Lord Grenville, George Canning, Lord Goderich, Lord Melbourne, Sir Robert Peel, Disraeli, Gladstone, Lord Salisbury and Neville Chamberlain were all Lincoln’s Inn; and Winston Churchill and Edward Heath were Gray’s Inn; and Eden, Macmillan, Major and Cameron Middle Temple; and Callaghan Inner Temple.

Herbert Henry Asquith, born 1852, was PM from 1908-1916. He excelled as an undergraduate in classics at Oxford, was called to the Bar by Lincoln’s Inn and practised at the Bar, with some success, though did not take silk. He was drawn into politics, aged 34, and soon excelled in public office under PM Gladstone. Asquith was the perfect peace-time PM. But he proved unequal to the task of leading the country in World War I, and was forced to resign in 1916, never able to inspire the nation.

David Lloyd George, born 1863 in Wales, qualified as a solicitor as a young man and engaged in small-time practice in North Wales. But he had political ambitions from the start; MP in 1890 aged 27. He was bilingual Welsh and English, and a truly fine speaker. Many said that from experience he had developed the pulpit manner. He clearly had high political aspirations, right from the beginning. In office from 1905 he soon dominated the House of Commons, and brought in old age pensions and curbed the powers of the House of Lords. In WWI he organised the production of munitions in 1915 and 1916-1918 he led the nation to victory. Unfortunately, the negotiated peace in the Treaty of Versailles was not a success, nor was his peace-time premiership.

Clement Atlee, born 1883, was a somewhat shy seemingly unambitious man, called to the Bar by Inner Temple in 1906 aged 23. He practised for a few years, but without much enthusiasm. Charitable work in the East End of London suited him better. Wounded in WWI, he never returned to the Bar. His political career was largely governed by chance. The Labour Party leadership fell vacant in 1935, and he became Leader. Deputy PM in 1940 in Winston Churchill’s coalition government, Atlee went on to win a landslide political victory at the end of the war in 1945. He was easily underestimated. He kept control of a cabinet of egotistical men; he wasted no words; he developed a quiet but highly effective leadership; he carried through a vast legislative programme.

Margaret Thatcher, born 1925, came from a modest middle class Methodist background, read Chemistry at Oxford, and started work as a research chemist. By age 24 she was a parliamentary candidate, trying several times, ultimately elected 1959 aged 34. Meanwhile she qualified as a barrister, Lincoln’s Inn, specialising in tax. As Leader of the Opposition, always a powerful opponent. In office 11½ years, ultimately she achieved the Order of Merit and the Garter, and was given a virtual state funeral, equalled only by Winston Churchill. Her law stood her in very good stead.

Tony Blair read law at Oxford, was called by Lincoln’s, started as a pupil in the chambers of Derry Irvine (a leading Labour activist), married a fellow pupil in the same chambers, and seemed well set for a legal career. But aged 29 he was seeking a parliamentary seat, aged 30 he had one, and by 41 he was the Leader of the Labour Party. By 44 he was PM (and appointed Derry Irvine as Lord Chancellor). His three successful general elections, his ten years in office, and some political achievements, were clouded by the general perception (after the event) that his involvement in the Iraq was a serious mistake. As a lawyer could he or should he have avoided that mistake?

Asquith, Lloyd George, Atlee, Thatcher and Blair all showed themselves in their early years to be capable lawyers. But all set their minds on a political career, and all brought their legal skills, along with other skills, to bear upon generally successful careers as PM.

Sir Keir Starmer – the only openly aspiring lawyer-PM today

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar