*/

National courts are now running the bulk of the world’s war crimes cases and corporate prosecutions are part of this growing trend, reports Chris Stephen

Corporate prosecutions are the new front in war crimes justice. In September 2023, Sweden began the trial of two former oil executives charged with complicity in atrocities in Sudan. Ian Lundin and Alex Schneiter, former Chairman and Chief Executive of Lundin Oil, are the first oil executives in history to be charged with war crimes. In December, France’s supreme court ruled that executives from construction giant Lafarge could be charged with crimes against humanity for allegedly aiding Islamic State in Syria. Meanwhile Switzerland is investigating a commodities trader and smelting company for allegedly conspiring with warlords in Democratic Republic of Congo.

The idea of indicting corporations who support warlords is not new. Back in 2003, Luis Moreno Ocampo, the first Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), announced his intention to investigate mining groups working with armed groups in Congo.

He told the Assembly of States parties, the ICC’s governing body: ‘Those who direct mining operations, sell diamonds or gold extracted in these conditions, launder the dirty money or provide weapons could also be authors of the crimes, even if they are based in other countries.’

Ocampo announced he had the legal ammunition to charge corporations with aiding and abetting crimes of warlords they did business with. However, the ICC never made good on its intentions, and never indicted a corporate executive. One reason for this is likely the complexity of these cases, which are a challenge for a chronically under-funded prosecution department.

War crimes cases are already complicated: They are in effect two-trials-in-one. First is the prosecution of the actual crimes on the battlefield, followed by the task of linking them to a senior commander. Investigating corporations accused of funding that commander adds a further level of complexity. The fact that the ICC has shied away from these cases comes with the court having struggled to impose itself generally. In its first 20 years, it has jailed just five war criminals.

Researching my book, The Future of War Crimes Justice, I was struck by how, in recent years, international courts have faded from the scene and the spotlight has moved to national courts. National courts now run the bulk of the world’s war crimes cases, and corporate prosecutions are part of this growing trend.

‘The very fact you have Switzerland, Sweden, France focusing on something relatively new, corporate responsibility, is very positive,’ says Dr Mark Ellis, Executive Director of the International Bar Association.

Research by academics Maximo Lander and Mackenzie Easson published by the European Journal of International Law shows the steady growth of universal jurisdiction cases, in which national courts prosecute war crimes cases worldwide. There were 342 cases in the decade to 1997, 503 the following decade, and 815 in the 10 years to 2019.

Laws allowing universal jurisdiction prosecutions have been around for decades, enshrined in the Geneva and Torture conventions. What is new is the appetite of governments, mostly in Europe, to fund such investigations, even when they involve the complexity of corporate crimes.

‘The Lundin case demonstrates a growing willingness of national prosecutors to take on cases involving crimes allegedly committed thousands of miles away,’ says John Balouziyeh, an international lawyer with Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt and Mosel LLP. ‘This is particularly the case in jurisdictions such as France, which have specialised war crimes units.’

Just as importantly, if they get the funding, prosecutors like chasing corporate war criminals. ‘It is easier to prosecute a national company for war crimes than the war criminals themselves,’ said Dr Louis Boré, a lawyer at the Supreme Court Bar in France. ‘It is easy to locate them and investigate them. They have archives where investigators can look for evidence.’

France is leading the field in corporate war crimes prosecutions, with 14 cases under way. Among companies being investigated are BNP Paribas bank for alleged crimes in Sudan and drinks-maker Group Castel for possible collusion in war crimes in Central African Republic.

Lafarge has already pled guilty to collusion with Islamic State in a US civil case prosecuted by the Justice Department in 2022. The company was fined $778 million for aiding the terrorist group. Quoted on the US Justice Department website, FBI director Paul Abbate said: ‘This guilty plea is a result of extraordinary collaboration among the FBI, the Department of Justice and our international partners.’

National war crimes prosecutors have extra help, in the form of reports from a new breed of human rights group. These groups scour the world for corporate war crimes. The basis for the Lundin prosecution was a report by the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan. The Lafarge case was the result of investigations by Paris-based Sherpa, while investigations into mining companies in Congo began with reports from Swiss-based TRIAL.

‘You have a very active prosecution of war crimes in France not because of the judges, but because of associations, such as Sherpa, which are litigators upheld by a network of experts, academics and lawyers to initiate actions against multinationals,’ said Julie Fabreguettes, an international law specialist attorney with VingtRue Avocats in Paris.

One motivation for this focus on corporations is the acknowledgement of the power they wield. Sixty-nine of the richest 100 entities in the world are not nations, but corporations. There is a belief among rights groups and prosecutors that a few crunchy prosecutions against corporations will have an outsize effect on the world’s boardrooms.

‘If it was better understood as a risk in corporate circles, the potential exposure of corporate officers to ICC jurisdiction could significantly influence the conduct of multinational corporations in situations of atrocities crimes,’ wrote professor David Scheffer, a former US war crimes ambassador.

The current wave of cases are against company bosses personally, not their companies. For the moment, war law does not allow criminal trials against corporations, only against their directors as individuals. Scheffer is among scholars calling for a change in the law so corporations can be classed as ‘judicial persons,’ and face criminal charges. However, others think the current system works better, because it puts the onus on the individuals who make decisions in a company. Company directors, goes the argument, will pay more attention to war law probes if they know they will be held personally responsible, with the possibility of jail sentences.

The big unknown is whether corporate war crimes cases, fine on paper, will work in practice. The Lundin case is already scheduled to be the longest criminal trial in Swedish history, with closing arguments not due until March 2026. The Lundin defendants are contesting the charges, insisting atrocities committed in Sudan were part of a civil war, and not connected to their operations. Switzerland began investigating corporate war crimes in Congo in 2002, following a UN report that accused 85 corporations of links to armed groups. Yet so far there have been no trials.

While the number of corporate war crimes cases remains small for now, boardrooms around the world are starting to take notice: ‘It is fair to say many businesses are starting to wake up and smell the coffee,’ said Tracy Shuchart, chief executive of US commodities analyst Hightower Resource Advisors. ‘There are only a handful of corporate war crimes cases now, but the signs are that they are a growing trend.’

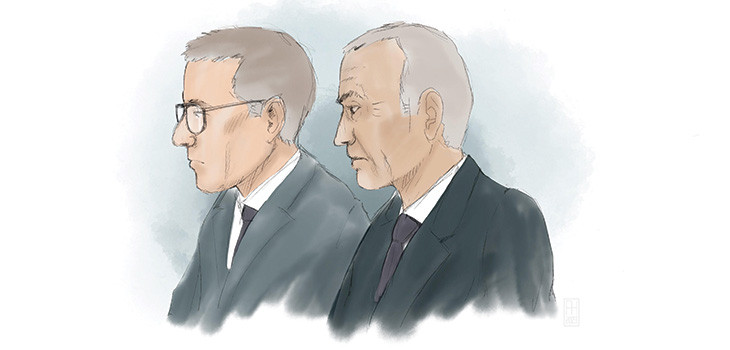

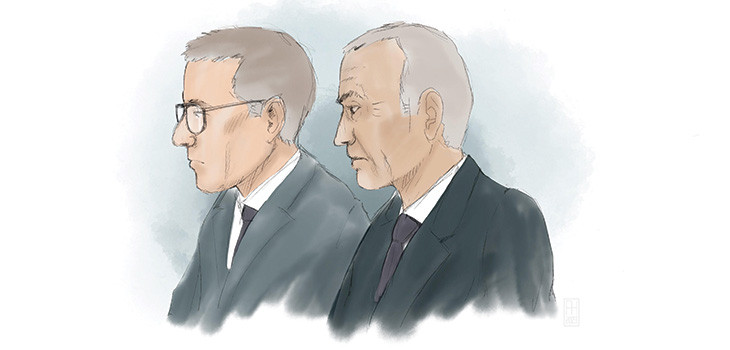

Pictured above: In South Sudan, Ruei Bawar Jieth, whose family was among the thousands of Sudanese people killed during the ‘oil wars’, stands in ‘Lundin’s Road’. Pictured top: In Sweden, an artist’s impression from Stockholm District Court where the main hearing began against Alex Schneiter (left) and Ian Lundin (right) on 5 September 2023.

The Future of War Crimes Justice by Chris Stephen ponders the future of prosecuting war criminals, including the case for pursuing corporations and banks who fund warlords. It is part of Melville House UK’s FUTURES series, which explores topical ideas that can help change the public conversation about our collective future.

Corporate prosecutions are the new front in war crimes justice. In September 2023, Sweden began the trial of two former oil executives charged with complicity in atrocities in Sudan. Ian Lundin and Alex Schneiter, former Chairman and Chief Executive of Lundin Oil, are the first oil executives in history to be charged with war crimes. In December, France’s supreme court ruled that executives from construction giant Lafarge could be charged with crimes against humanity for allegedly aiding Islamic State in Syria. Meanwhile Switzerland is investigating a commodities trader and smelting company for allegedly conspiring with warlords in Democratic Republic of Congo.

The idea of indicting corporations who support warlords is not new. Back in 2003, Luis Moreno Ocampo, the first Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), announced his intention to investigate mining groups working with armed groups in Congo.

He told the Assembly of States parties, the ICC’s governing body: ‘Those who direct mining operations, sell diamonds or gold extracted in these conditions, launder the dirty money or provide weapons could also be authors of the crimes, even if they are based in other countries.’

Ocampo announced he had the legal ammunition to charge corporations with aiding and abetting crimes of warlords they did business with. However, the ICC never made good on its intentions, and never indicted a corporate executive. One reason for this is likely the complexity of these cases, which are a challenge for a chronically under-funded prosecution department.

War crimes cases are already complicated: They are in effect two-trials-in-one. First is the prosecution of the actual crimes on the battlefield, followed by the task of linking them to a senior commander. Investigating corporations accused of funding that commander adds a further level of complexity. The fact that the ICC has shied away from these cases comes with the court having struggled to impose itself generally. In its first 20 years, it has jailed just five war criminals.

Researching my book, The Future of War Crimes Justice, I was struck by how, in recent years, international courts have faded from the scene and the spotlight has moved to national courts. National courts now run the bulk of the world’s war crimes cases, and corporate prosecutions are part of this growing trend.

‘The very fact you have Switzerland, Sweden, France focusing on something relatively new, corporate responsibility, is very positive,’ says Dr Mark Ellis, Executive Director of the International Bar Association.

Research by academics Maximo Lander and Mackenzie Easson published by the European Journal of International Law shows the steady growth of universal jurisdiction cases, in which national courts prosecute war crimes cases worldwide. There were 342 cases in the decade to 1997, 503 the following decade, and 815 in the 10 years to 2019.

Laws allowing universal jurisdiction prosecutions have been around for decades, enshrined in the Geneva and Torture conventions. What is new is the appetite of governments, mostly in Europe, to fund such investigations, even when they involve the complexity of corporate crimes.

‘The Lundin case demonstrates a growing willingness of national prosecutors to take on cases involving crimes allegedly committed thousands of miles away,’ says John Balouziyeh, an international lawyer with Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt and Mosel LLP. ‘This is particularly the case in jurisdictions such as France, which have specialised war crimes units.’

Just as importantly, if they get the funding, prosecutors like chasing corporate war criminals. ‘It is easier to prosecute a national company for war crimes than the war criminals themselves,’ said Dr Louis Boré, a lawyer at the Supreme Court Bar in France. ‘It is easy to locate them and investigate them. They have archives where investigators can look for evidence.’

France is leading the field in corporate war crimes prosecutions, with 14 cases under way. Among companies being investigated are BNP Paribas bank for alleged crimes in Sudan and drinks-maker Group Castel for possible collusion in war crimes in Central African Republic.

Lafarge has already pled guilty to collusion with Islamic State in a US civil case prosecuted by the Justice Department in 2022. The company was fined $778 million for aiding the terrorist group. Quoted on the US Justice Department website, FBI director Paul Abbate said: ‘This guilty plea is a result of extraordinary collaboration among the FBI, the Department of Justice and our international partners.’

National war crimes prosecutors have extra help, in the form of reports from a new breed of human rights group. These groups scour the world for corporate war crimes. The basis for the Lundin prosecution was a report by the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan. The Lafarge case was the result of investigations by Paris-based Sherpa, while investigations into mining companies in Congo began with reports from Swiss-based TRIAL.

‘You have a very active prosecution of war crimes in France not because of the judges, but because of associations, such as Sherpa, which are litigators upheld by a network of experts, academics and lawyers to initiate actions against multinationals,’ said Julie Fabreguettes, an international law specialist attorney with VingtRue Avocats in Paris.

One motivation for this focus on corporations is the acknowledgement of the power they wield. Sixty-nine of the richest 100 entities in the world are not nations, but corporations. There is a belief among rights groups and prosecutors that a few crunchy prosecutions against corporations will have an outsize effect on the world’s boardrooms.

‘If it was better understood as a risk in corporate circles, the potential exposure of corporate officers to ICC jurisdiction could significantly influence the conduct of multinational corporations in situations of atrocities crimes,’ wrote professor David Scheffer, a former US war crimes ambassador.

The current wave of cases are against company bosses personally, not their companies. For the moment, war law does not allow criminal trials against corporations, only against their directors as individuals. Scheffer is among scholars calling for a change in the law so corporations can be classed as ‘judicial persons,’ and face criminal charges. However, others think the current system works better, because it puts the onus on the individuals who make decisions in a company. Company directors, goes the argument, will pay more attention to war law probes if they know they will be held personally responsible, with the possibility of jail sentences.

The big unknown is whether corporate war crimes cases, fine on paper, will work in practice. The Lundin case is already scheduled to be the longest criminal trial in Swedish history, with closing arguments not due until March 2026. The Lundin defendants are contesting the charges, insisting atrocities committed in Sudan were part of a civil war, and not connected to their operations. Switzerland began investigating corporate war crimes in Congo in 2002, following a UN report that accused 85 corporations of links to armed groups. Yet so far there have been no trials.

While the number of corporate war crimes cases remains small for now, boardrooms around the world are starting to take notice: ‘It is fair to say many businesses are starting to wake up and smell the coffee,’ said Tracy Shuchart, chief executive of US commodities analyst Hightower Resource Advisors. ‘There are only a handful of corporate war crimes cases now, but the signs are that they are a growing trend.’

Pictured above: In South Sudan, Ruei Bawar Jieth, whose family was among the thousands of Sudanese people killed during the ‘oil wars’, stands in ‘Lundin’s Road’. Pictured top: In Sweden, an artist’s impression from Stockholm District Court where the main hearing began against Alex Schneiter (left) and Ian Lundin (right) on 5 September 2023.

The Future of War Crimes Justice by Chris Stephen ponders the future of prosecuting war criminals, including the case for pursuing corporations and banks who fund warlords. It is part of Melville House UK’s FUTURES series, which explores topical ideas that can help change the public conversation about our collective future.

National courts are now running the bulk of the world’s war crimes cases and corporate prosecutions are part of this growing trend, reports Chris Stephen

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, explains why drugs may appear in test results, despite the donor denying use of them

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Ready for the new way to do tax returns? David Southern KC continues his series explaining the impact on barristers. In part 2, a worked example shows the specific practicalities of adapting to the new system

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar