*/

I like to think that I know how to tell stories. After all, as a trial lawyer, I spend my daylight hours, and a fair share of my night-time hours, telling stories. Most of these are set, literally, in international commercial and investment arbitrations. Stories that take the form of Requests for Arbitration, Memorials, and Rejoinders. Or they involve story-telling in the old-school way, orally, to a tribunal or a court.

Of course, the stories that I tell in these settings are bounded by what the documents, the witness statements and the expert reports recite, and also by what the applicable procedural rules permit. But, despite those boundaries, narration and language figures mightily in what we litigators do. Judges and arbitrators decide, of course, based on the law and the evidence. But they don’t ignore the stories that present those rules and facts – and many would say that those stories are one of the most important parts of any lawyer’s case.

It’s not that surprising, therefore, that so many lawyers end up being story-tellers of a different type. Think, for example, of Cicero, Geoffrey Chaucer, Franz Kafka, Honore de Balzac, James Boswell, Henry Fielding, Francois Rabelais, Johan von Goethe, Jules Vernes, Washington Irving, Wallace Stevens, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, E.T.A. Hoffman, Louis Auchincloss, Marjorie Liu, and John Grisham. All lawyers. And mostly litigators. I have nothing against bond indentures, but they may lend themselves less seamlessly to novels than closing arguments.

My own experience is that writing fiction is a world apart from legal writing. Writing for a court, an arbitral tribunal or a client is, as I said, bounded on so many sides – by procedural rules, by the law, by the evidence, by rules of professional conduct and by the court.

Fiction is mostly the opposite. When you sit down to write a spy thriller, almost everything is up for grabs. Almost every possibility is open. Who are the characters? Where does it take place? What happens and how? You start with a blank piece of paper and the entire world, and all the worlds you can conceive, can end up on that page. You narrow your options a bit as you write. The characters have to be ‘true’, both to their own characters and to external plausibility. As does the plot. But those are only the thinnest of constraints.

Where does the material to fill that unbounded, blank page come from? Every author has their own inspirations, and every page, like every author, is also different. For me, though, the inspirations come from people, places, past works by other authors, songs and films – all the stuff of life that gets reworked before filling up the blank page.

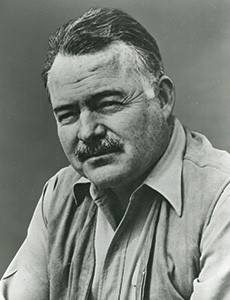

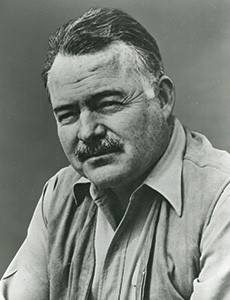

Like many lawyers, I love films about lawyers – A Few Good Men, Paper Chase, 12 Angry Men, A Man for All Seasons and others are classics. But, to be honest, I prefer films, books and songs that aren’t about lawyers – and that are instead about life outside the courtroom. Those lives – whether in Hemingway’s wartime novels, or George R.R. Martin’s fantasies, or Rudyard Kipling’s mix of both, or John le Carre’s spy thrillers – tell stories about characters who are more universal and more human. And, at least for me, stories and characters that provide more inspiration for other stories.

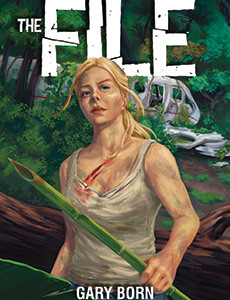

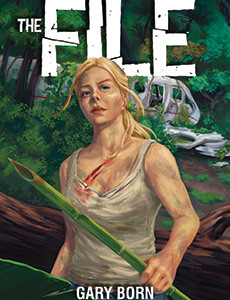

Places and people do the same, providing inspiration for that blank page. I love the outdoors – whether the Rwenzori Mountains on the border of Uganda and Congo or the Italian Alps, north of Lake Como. The grandeur and emptiness of those mountains provided inspiration for both early and later scenes in my first novel, The File, framing and then focusing attention on the characters.

City scenes do the same. One of my favourite cities is, perhaps a little suprisingly, Zurich. It fully deserves its reputation as the world’s most livable city – combining the beauty of the Alps (again…) and Lake Zurich with exceptional creature comforts of food, drink, music, art and interesting people. But it’s not always that high on places to visit. That’s a bit of a shame. I think Zurich conceals its true self beneath the comforts and pleasant order, a little like its Winter Snowman Bonfire (the Sechselaeuten). But more on that, again, in The File, which concludes on the shores of the Lake, not far from the boutiques and pastry houses on Bahnhofstrasse.

In the end, though, all these inspirations end up in front of that blank page any author confronts. And the joy, and the other emotions, of writing comes from trying to capture those inspirations and capture them on an empty piece of paper for others to share.

The Rwenzori Mountains, Uganda

Ernest Hemingway

The Winter Snowman Bonfire in Zurich

I like to think that I know how to tell stories. After all, as a trial lawyer, I spend my daylight hours, and a fair share of my night-time hours, telling stories. Most of these are set, literally, in international commercial and investment arbitrations. Stories that take the form of Requests for Arbitration, Memorials, and Rejoinders. Or they involve story-telling in the old-school way, orally, to a tribunal or a court.

Of course, the stories that I tell in these settings are bounded by what the documents, the witness statements and the expert reports recite, and also by what the applicable procedural rules permit. But, despite those boundaries, narration and language figures mightily in what we litigators do. Judges and arbitrators decide, of course, based on the law and the evidence. But they don’t ignore the stories that present those rules and facts – and many would say that those stories are one of the most important parts of any lawyer’s case.

It’s not that surprising, therefore, that so many lawyers end up being story-tellers of a different type. Think, for example, of Cicero, Geoffrey Chaucer, Franz Kafka, Honore de Balzac, James Boswell, Henry Fielding, Francois Rabelais, Johan von Goethe, Jules Vernes, Washington Irving, Wallace Stevens, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, E.T.A. Hoffman, Louis Auchincloss, Marjorie Liu, and John Grisham. All lawyers. And mostly litigators. I have nothing against bond indentures, but they may lend themselves less seamlessly to novels than closing arguments.

My own experience is that writing fiction is a world apart from legal writing. Writing for a court, an arbitral tribunal or a client is, as I said, bounded on so many sides – by procedural rules, by the law, by the evidence, by rules of professional conduct and by the court.

Fiction is mostly the opposite. When you sit down to write a spy thriller, almost everything is up for grabs. Almost every possibility is open. Who are the characters? Where does it take place? What happens and how? You start with a blank piece of paper and the entire world, and all the worlds you can conceive, can end up on that page. You narrow your options a bit as you write. The characters have to be ‘true’, both to their own characters and to external plausibility. As does the plot. But those are only the thinnest of constraints.

Where does the material to fill that unbounded, blank page come from? Every author has their own inspirations, and every page, like every author, is also different. For me, though, the inspirations come from people, places, past works by other authors, songs and films – all the stuff of life that gets reworked before filling up the blank page.

Like many lawyers, I love films about lawyers – A Few Good Men, Paper Chase, 12 Angry Men, A Man for All Seasons and others are classics. But, to be honest, I prefer films, books and songs that aren’t about lawyers – and that are instead about life outside the courtroom. Those lives – whether in Hemingway’s wartime novels, or George R.R. Martin’s fantasies, or Rudyard Kipling’s mix of both, or John le Carre’s spy thrillers – tell stories about characters who are more universal and more human. And, at least for me, stories and characters that provide more inspiration for other stories.

Places and people do the same, providing inspiration for that blank page. I love the outdoors – whether the Rwenzori Mountains on the border of Uganda and Congo or the Italian Alps, north of Lake Como. The grandeur and emptiness of those mountains provided inspiration for both early and later scenes in my first novel, The File, framing and then focusing attention on the characters.

City scenes do the same. One of my favourite cities is, perhaps a little suprisingly, Zurich. It fully deserves its reputation as the world’s most livable city – combining the beauty of the Alps (again…) and Lake Zurich with exceptional creature comforts of food, drink, music, art and interesting people. But it’s not always that high on places to visit. That’s a bit of a shame. I think Zurich conceals its true self beneath the comforts and pleasant order, a little like its Winter Snowman Bonfire (the Sechselaeuten). But more on that, again, in The File, which concludes on the shores of the Lake, not far from the boutiques and pastry houses on Bahnhofstrasse.

In the end, though, all these inspirations end up in front of that blank page any author confronts. And the joy, and the other emotions, of writing comes from trying to capture those inspirations and capture them on an empty piece of paper for others to share.

The Rwenzori Mountains, Uganda

Ernest Hemingway

The Winter Snowman Bonfire in Zurich

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar