*/

‘Penitenziagite! Watch out for the draco who cometh in futurum to gnaw on your anima! La morte est supra nos!’ On New Year’s Eve 1988 I watched Jean-Jacques Annaud’s extraordinary film version of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose. Quite unexpectedly, it changed my life. Overnight, I became obsessed with everything medieval.

After studying law and then medieval history in England and France, I ended up handing in a doctoral thesis on the Knights Templar and Hospitaller, and happily telling my examiners I was heading off to the Bar. ‘Well,’ one of them nodded, a little wistfully, ‘you’ll meet more medievalists in the Temple than you will here.’ I am not sure that turned out to be true, but my chambers were 50 metres from Temple Church, and its recumbent stone effigies continued to mesmerise me.

I am supposed to mention music and other things that inspire me, so I’ll recommend Pérotin as a transcendent accompaniment for any visit to Temple Church. Try the version of his Beata viscera recorded by the Hilliard Ensemble. Basses provide a steady, stable drone, while a lone voice languidly swoops and soars above it.

As lawyers we are surrounded by documents. Heaps of them that litter our shelves and minds. Yet each one comes with its own questions. Who wrote it? Who read it? Did readers believe it? Can we? Umberto Eco (yes, him again) explores this hilariously in Foucault’s Pendulum, in which a mysterious fragmentary message turns out not to be the masterplan of an occult society, but an abbreviated shopping list.

Some years ago, the Daily Telegraph asked me to write a non-political piece every day on a historical anniversary. This partially coincided with the Brexit referendum. Britain has a lot of history, so many of the events I wrote about occurred before the Reformation and Empire, when Britain shared its religious, political and economic fabric with western Europe. I found it fascinating that such pieces caused some readers a degree of apoplexy.

I’d better break for another piece of music. I will go for Medusa by the New York thrash band, Anthrax. If that doesn’t get you moving in the morning (possibly to the off button), nothing will. And maybe a hymn of praise to the Gorgoneion could help get Britain back on its feet.

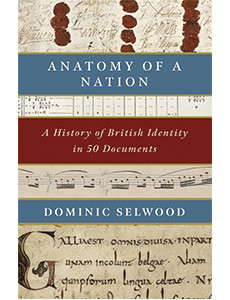

Those readers from the Daily Telegraph who responded to my pieces by muttering in the comments that Dominic doesn’t sound like a very British name, or that I don’t look 100% white, got me thinking. What does it mean to be British? How do we define ourselves? How do others see us? And how have the answers to these questions changed over time? I went back to Caesar, Celtic bards, Gildas, Anglo-Saxon and Viking poets, Anglo-French chroniclers, medieval songwriters and lovers, Tudor ministers, witch-hunting court clerks, Jacobite terrorists, Puritans and Cavaliers, early experimental scientists, pioneer Romantics, Victorian inventors, First World War satirists and classical composers, and a cast of others to see what they recorded in a variety of documents ranging from words to music and painting. The result is Anatomy of a Nation: A History of British Identity in 50 Documents.

Now I have mentioned the Romantics, I can move on to art I find inspiring. The book includes William Blake’s poem Jerusalem from his epic Milton: A Poem in 2 Books, created from 1804 to 1811. I say ‘created’ because Blake never just wrote. He etched, engraved, illustrated, painted, printed and bound. Although written off in his lifetime as an ‘unfortunate lunatic’ with a ‘distempered brain’, he was discovered by the barrister Alexander Gilchrist, and is now celebrated for his irrepressible creativity. He has always been a hero, and it is a thrill to have him in the book.

After looking at all these documents, my conclusion is that Britain has had many identities. Our inability to see beyond Churchill and Empire does us no favours in finding solutions for operating in the world of the 21st century. But if we look all the way back to 950,000 BC, to the many different cultures Britain has hosted, often simultaneously, we may start to be able to chart a way forward.

And, finally, some inspirational objects. On my desk I have the goggle-eyed berserker from the Lewis Chess Pieces – hilariously biting his shield – and the sedentary bishop, propping himself up with his crozier to counter the boredom of being. They were probably made in Norway, and attest to the Gaelic-Norse culture of the period in the Hebrides. I expect there would be those who would say they don’t seem very British. But they are. Just not Churchill and Empire British.

‘Penitenziagite! Watch out for the draco who cometh in futurum to gnaw on your anima! La morte est supra nos!’ On New Year’s Eve 1988 I watched Jean-Jacques Annaud’s extraordinary film version of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose. Quite unexpectedly, it changed my life. Overnight, I became obsessed with everything medieval.

After studying law and then medieval history in England and France, I ended up handing in a doctoral thesis on the Knights Templar and Hospitaller, and happily telling my examiners I was heading off to the Bar. ‘Well,’ one of them nodded, a little wistfully, ‘you’ll meet more medievalists in the Temple than you will here.’ I am not sure that turned out to be true, but my chambers were 50 metres from Temple Church, and its recumbent stone effigies continued to mesmerise me.

I am supposed to mention music and other things that inspire me, so I’ll recommend Pérotin as a transcendent accompaniment for any visit to Temple Church. Try the version of his Beata viscera recorded by the Hilliard Ensemble. Basses provide a steady, stable drone, while a lone voice languidly swoops and soars above it.

As lawyers we are surrounded by documents. Heaps of them that litter our shelves and minds. Yet each one comes with its own questions. Who wrote it? Who read it? Did readers believe it? Can we? Umberto Eco (yes, him again) explores this hilariously in Foucault’s Pendulum, in which a mysterious fragmentary message turns out not to be the masterplan of an occult society, but an abbreviated shopping list.

Some years ago, the Daily Telegraph asked me to write a non-political piece every day on a historical anniversary. This partially coincided with the Brexit referendum. Britain has a lot of history, so many of the events I wrote about occurred before the Reformation and Empire, when Britain shared its religious, political and economic fabric with western Europe. I found it fascinating that such pieces caused some readers a degree of apoplexy.

I’d better break for another piece of music. I will go for Medusa by the New York thrash band, Anthrax. If that doesn’t get you moving in the morning (possibly to the off button), nothing will. And maybe a hymn of praise to the Gorgoneion could help get Britain back on its feet.

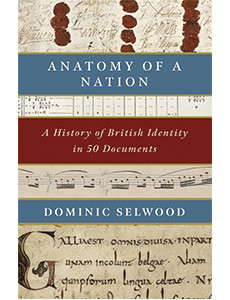

Those readers from the Daily Telegraph who responded to my pieces by muttering in the comments that Dominic doesn’t sound like a very British name, or that I don’t look 100% white, got me thinking. What does it mean to be British? How do we define ourselves? How do others see us? And how have the answers to these questions changed over time? I went back to Caesar, Celtic bards, Gildas, Anglo-Saxon and Viking poets, Anglo-French chroniclers, medieval songwriters and lovers, Tudor ministers, witch-hunting court clerks, Jacobite terrorists, Puritans and Cavaliers, early experimental scientists, pioneer Romantics, Victorian inventors, First World War satirists and classical composers, and a cast of others to see what they recorded in a variety of documents ranging from words to music and painting. The result is Anatomy of a Nation: A History of British Identity in 50 Documents.

Now I have mentioned the Romantics, I can move on to art I find inspiring. The book includes William Blake’s poem Jerusalem from his epic Milton: A Poem in 2 Books, created from 1804 to 1811. I say ‘created’ because Blake never just wrote. He etched, engraved, illustrated, painted, printed and bound. Although written off in his lifetime as an ‘unfortunate lunatic’ with a ‘distempered brain’, he was discovered by the barrister Alexander Gilchrist, and is now celebrated for his irrepressible creativity. He has always been a hero, and it is a thrill to have him in the book.

After looking at all these documents, my conclusion is that Britain has had many identities. Our inability to see beyond Churchill and Empire does us no favours in finding solutions for operating in the world of the 21st century. But if we look all the way back to 950,000 BC, to the many different cultures Britain has hosted, often simultaneously, we may start to be able to chart a way forward.

And, finally, some inspirational objects. On my desk I have the goggle-eyed berserker from the Lewis Chess Pieces – hilariously biting his shield – and the sedentary bishop, propping himself up with his crozier to counter the boredom of being. They were probably made in Norway, and attest to the Gaelic-Norse culture of the period in the Hebrides. I expect there would be those who would say they don’t seem very British. But they are. Just not Churchill and Empire British.

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar