*/

Is failure to confront the root cause of vaccine hesitancy driving people towards anti-vax views? Natasha Isaac examines how pervasive conspiracy theories about coronavirus vaccines have become

At the end of 2020 my grandfather, a retired solicitor, contacted me, worried about two pieces of information he had been sent by a friend about the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine. One warned of a woman allegedly found frothing at the mouth days after receiving the vaccine. The other was a video which dramatically described the alleged onset of facial palsy in one person following the injection. At 89, and with heart and lung conditions, my grandfather is anxious to be protected from the virus.

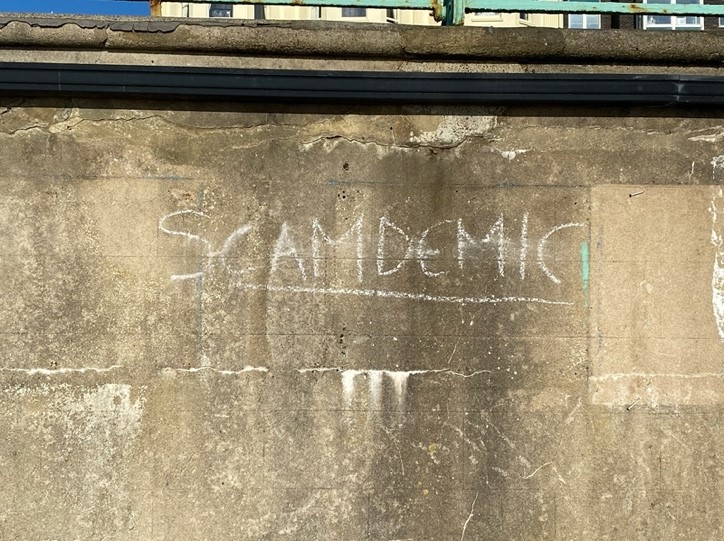

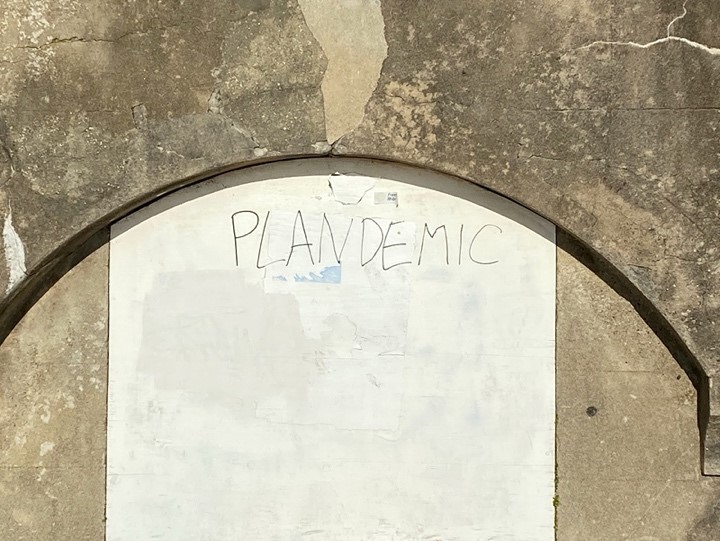

I was upset that a friend whom my grandfather trusted would try to prevent him from accessing healthcare which could save his life. However, this made me realise just how pervasive conspiracy theories about coronavirus vaccines have become in the wake of more generalised scepticism surrounding the vaccines.

The UK Human Rights Blog published a post by editor Rosalind English, a barrister and former academic, last year exploring ‘vaccine hesitancy’, which the World Health Organization describes as ‘the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines’. The post was in the context of a scenario of a compulsory vaccination programme in the UK. Vaccines are not currently compulsory within the UK, and the blog points out that: ‘Compulsory interference with a person’s bodily integrity is not something that a democratic society will tolerate without detailed regulations and specialist tribunals in place.’

English also notes that societal pressures have played a part in compliance with childhood vaccinations so far, however there are several cases in which parents have opposed vaccinations for their children. The M v H case in December 2020 pre-emptively attempted to address the coronavirus vaccine alongside the MMR vaccine. The court ordered that it was in the children’s best interests to receive the MMR vaccine, but that it was premature to make any order regarding the coronavirus vaccine. The judge did remark that this was not an indication that there was any doubt on the part of the court about the efficacy of the vaccine.

A key purpose of any vaccination programme is to achieve herd immunity. Herd immunity is when a threshold is reached whereby in addition to protecting the vaccinated individual, the infection is no longer transmitted between people and therefore cannot survive within the population because a certain proportion of the population is either vaccinated, or has caught the infection and generated their own immune response. This is important because it protects those for whom a vaccine may not provide sufficient protection, as well as those who are unable to have vaccines for medical reasons.

The UK has now approved three vaccines for use, but it seems we have a growing obstacle to overcome in the form of vaccine hesitancy and anti-vax movements. There is a distinction between the two, however there is a risk that the ‘vaccine hesitant’ may become drawn to anti-vax movements.

This phenomenon is explained in a video produced by The Economist and Mishcon de Reya - Now & Next - which addresses why vaccine mistrust is growing. In the video, Professor Heidi Larson (director of the Vaccine Confidence Project) discusses the fact that the failure to confront the root cause of vaccine hesitancy drives people towards anti-vax views. Some people, she says, have genuine questions and are open to discussion but they then migrate to anti-vax movements who seem to acknowledge and endorse their concerns. Her argument is that the failure of the medical establishment to listen to parents who have doubts, and feel they are being judged, is not helpful in trying to support people in decision making. Fundamentally, Professor Larson states, this is about trust, and there has been an opportunity missed to build trust in this pandemic where Professor Larson feels the voice of the patient should have been given much more care and attention at this uncertain time. She states that it is not just numbers that we are seeing in our hospitals but humans who require empathy - the legacy of Andrew Wakefield’s dishonest MMR research looms large for many who will need reassurance.

Jonathan Van Tam, Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England, markedly refused to comment on anti-vax movements and their theories in a government briefing. It’s difficult to know if this is the right tactic to counter the movements and their messaging which seems to be spreading faster than ever. The legal community is not immune to scandalising itself in the face of what it perceives to be popular opinion. We seem to have become prone to assuming that the man on the street opposes what our right-thinking internet-based bubble knows to be ‘correct’. In reality there is clearly a more diverse, and perhaps rather more apathetic mindset to issues which legal Twitter cares about. Is this the same with the anti-vax movement? Are they less dangerous than we think they are and should we, like JVT, just ignore their misinformation?

A poll conducted by YouGov/The Economist found that 67% of Britons would take the vaccine, with one in five (21%) saying they are unlikely to get it and 12% unsure. According to the anti-extremism charity Hope Not Hate’s 2020 polling in the USA, 28% of Americans surveyed felt it 'either definitely or probably true' that COVID-19 has been intentionally released as part of a depopulation plan orchestrated by the United Nations or new world order; with 15% of the view that ‘a COVID-19 vaccine will be used maliciously to infect people with poison’. One in five Trump supporters said they were strongly opposed to a vaccine. Only one third of those polled said they would take a vaccine, with 23% saying they probably would. Clearly there is a link between those who believe conspiracy theories about the US government and those who believe that the vaccination programme is designed to cause harm.

While we may not be surprised by the statistics from the USA, Hope Not Hate also published research in July 2020 which notes that: ‘A Facebook group set up by British anti-vaccine campaigners in March has gained 145,000 members in less than three months, and plays host to alarming levels of Holocaust denial and antisemitic conspiracy theories.’ To me, it seems highly likely that extremist conspiracy theory groups online are likely to use the burgeoning vaccine scepticism as a means of spreading their ideology, rather than the other way around, but this may still have consequences for our nation - both in an immediate public health sense, and as we begin to see the spread of wider conspiracy theories in the UK. There does appear to be a strong link between those who are involved with anti-vaccine groups, and engagement with broader conspiracy theories.

One of the more vocal conspiracy theory movements in the USA is QAnon. Readers may have seen Jake Angeli, the ‘QAnon Shaman’ in his bison horns and fur storming into the US Capitol in January. QAnon was one of the first movements to propose the vaccine conspiracy theory involving Bill Gates and micro-chips, but its influence and theories encompass a wider range of topics. In her book, Going Dark published early in 2020, disinformation and extremism expert Julia Ebner describes the success of this group as ‘baffling’. She details the goals of the group’s small but vocal and growing UK offshoot Q Britannia as ‘to give the people of the UK somewhere to network, share information, archive and find ways to take back our country’.

This is the difficulty with conspiracy theorists, as opposed to vaccine hesitant people, and explains the need for us to engage with people as early on as possible, in an empathetic way as suggested by Professor Larson. By the time they reach the conspiracy theory movements they are seen, as CNN’s Don Lemon put it, as ‘literally nutty’ and it becomes as difficult for us to engage with them as for them to engage with us.

There is evidently an atmosphere of distrust and resentment brewing towards the government, and it will need to rebuild trust, with empathy and tech-savvy intelligence, before it can successfully conclude the vaccine programme, particularly if it wishes to eventually vaccinate children. If there is going to be a compulsory vaccine programme following an Act of Parliament - the messaging will be key to its success. The courts may well become involved if anti-vax groups seek to challenge an Act of Parliament, and will almost certainly be involved in the case of vaccine hesitant parents.

Another legal area in which arguments on this subject will play out is information regulation. In January 2021 Facebook, Instagram and Twitter took the drastic step of blocking Donald Trump, but since April 2020 Facebook has put warning labels on some posts and even banned anti-vax ads, much harmful content remains. Does Facebook therefore need to redesign its business model and algorithms to ensure it does not amplify this content? What are the ramifications for free speech and why are other extremist leaders not excluded from these platforms? Should Facebook just downgrade the malicious content? How can we encourage these companies to act, or should we legislate to force them to do so? I cannot pretend to have the answers to these questions, and any restrictions could just drive anti-vaxxers further into darker webspaces, like 4chan, which is already starting to happen in the UK.

Following the insurrectionist storming of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 the Community Security Trust (CST) published a blog highlighting posts on the website 4chan used by those in the UK who were eager and willing to replicate the actions of Trump’s supporters in the House of Commons. The CST stated that this is ‘yet another example of why internet regulation is urgently needed to help control the spread of online extremism, as Metropolitan Police Assistant Commissioner Neil Basu described’.

It’s important to remember that there is a difference between those who are sceptical of the new vaccines, and those who fervently believe that its introduction is an attempt to control their lives. What’s important now is how we respond to those who feel their concerns have not been heard to prevent further deaths from coronavirus but also perhaps even threats to our government and democracy.

Certainly, there are echoes of broader conspiracy theories in anti-vax theories. That the vaccine is going to be used with malicious or nefarious intent with the goal of exerting control by an elite, for example. If anti-vax conspiracy theories are becoming a gateway for people to become further involved with groups like Q Britannia, we need to learn the lessons of Trumpism, so that when the time comes to reap what we have sown the bad apples will have fallen away - whether that’s from lack of oxygen, effective intervention, or a combination of the two remains to be seen. Winning back the trust of those who may yet become involved in these movements via a sort of ‘anti-vax gateway’ is imperative.

I never met my other grandfather who arrived in this country on the Kindertransport, fleeing an extremist movement who were determined to disrupt liberal elites. I am certain that he would be wary of anti-vaxxers and conspiracy movements, but he would also be delighted that so far our country has been immune to the attacks on its values as seen in the USA in January 2021. It is my hope that we can prevent people from being sucked into extremism by finding empathy and by not simply dismissing the hesitant. Our vaccination programme may now be the trial run for an attempt at rebuilding trust in experts, and in our government and institutions.

At the end of 2020 my grandfather, a retired solicitor, contacted me, worried about two pieces of information he had been sent by a friend about the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine. One warned of a woman allegedly found frothing at the mouth days after receiving the vaccine. The other was a video which dramatically described the alleged onset of facial palsy in one person following the injection. At 89, and with heart and lung conditions, my grandfather is anxious to be protected from the virus.

I was upset that a friend whom my grandfather trusted would try to prevent him from accessing healthcare which could save his life. However, this made me realise just how pervasive conspiracy theories about coronavirus vaccines have become in the wake of more generalised scepticism surrounding the vaccines.

The UK Human Rights Blog published a post by editor Rosalind English, a barrister and former academic, last year exploring ‘vaccine hesitancy’, which the World Health Organization describes as ‘the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines’. The post was in the context of a scenario of a compulsory vaccination programme in the UK. Vaccines are not currently compulsory within the UK, and the blog points out that: ‘Compulsory interference with a person’s bodily integrity is not something that a democratic society will tolerate without detailed regulations and specialist tribunals in place.’

English also notes that societal pressures have played a part in compliance with childhood vaccinations so far, however there are several cases in which parents have opposed vaccinations for their children. The M v H case in December 2020 pre-emptively attempted to address the coronavirus vaccine alongside the MMR vaccine. The court ordered that it was in the children’s best interests to receive the MMR vaccine, but that it was premature to make any order regarding the coronavirus vaccine. The judge did remark that this was not an indication that there was any doubt on the part of the court about the efficacy of the vaccine.

A key purpose of any vaccination programme is to achieve herd immunity. Herd immunity is when a threshold is reached whereby in addition to protecting the vaccinated individual, the infection is no longer transmitted between people and therefore cannot survive within the population because a certain proportion of the population is either vaccinated, or has caught the infection and generated their own immune response. This is important because it protects those for whom a vaccine may not provide sufficient protection, as well as those who are unable to have vaccines for medical reasons.

The UK has now approved three vaccines for use, but it seems we have a growing obstacle to overcome in the form of vaccine hesitancy and anti-vax movements. There is a distinction between the two, however there is a risk that the ‘vaccine hesitant’ may become drawn to anti-vax movements.

This phenomenon is explained in a video produced by The Economist and Mishcon de Reya - Now & Next - which addresses why vaccine mistrust is growing. In the video, Professor Heidi Larson (director of the Vaccine Confidence Project) discusses the fact that the failure to confront the root cause of vaccine hesitancy drives people towards anti-vax views. Some people, she says, have genuine questions and are open to discussion but they then migrate to anti-vax movements who seem to acknowledge and endorse their concerns. Her argument is that the failure of the medical establishment to listen to parents who have doubts, and feel they are being judged, is not helpful in trying to support people in decision making. Fundamentally, Professor Larson states, this is about trust, and there has been an opportunity missed to build trust in this pandemic where Professor Larson feels the voice of the patient should have been given much more care and attention at this uncertain time. She states that it is not just numbers that we are seeing in our hospitals but humans who require empathy - the legacy of Andrew Wakefield’s dishonest MMR research looms large for many who will need reassurance.

Jonathan Van Tam, Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England, markedly refused to comment on anti-vax movements and their theories in a government briefing. It’s difficult to know if this is the right tactic to counter the movements and their messaging which seems to be spreading faster than ever. The legal community is not immune to scandalising itself in the face of what it perceives to be popular opinion. We seem to have become prone to assuming that the man on the street opposes what our right-thinking internet-based bubble knows to be ‘correct’. In reality there is clearly a more diverse, and perhaps rather more apathetic mindset to issues which legal Twitter cares about. Is this the same with the anti-vax movement? Are they less dangerous than we think they are and should we, like JVT, just ignore their misinformation?

A poll conducted by YouGov/The Economist found that 67% of Britons would take the vaccine, with one in five (21%) saying they are unlikely to get it and 12% unsure. According to the anti-extremism charity Hope Not Hate’s 2020 polling in the USA, 28% of Americans surveyed felt it 'either definitely or probably true' that COVID-19 has been intentionally released as part of a depopulation plan orchestrated by the United Nations or new world order; with 15% of the view that ‘a COVID-19 vaccine will be used maliciously to infect people with poison’. One in five Trump supporters said they were strongly opposed to a vaccine. Only one third of those polled said they would take a vaccine, with 23% saying they probably would. Clearly there is a link between those who believe conspiracy theories about the US government and those who believe that the vaccination programme is designed to cause harm.

While we may not be surprised by the statistics from the USA, Hope Not Hate also published research in July 2020 which notes that: ‘A Facebook group set up by British anti-vaccine campaigners in March has gained 145,000 members in less than three months, and plays host to alarming levels of Holocaust denial and antisemitic conspiracy theories.’ To me, it seems highly likely that extremist conspiracy theory groups online are likely to use the burgeoning vaccine scepticism as a means of spreading their ideology, rather than the other way around, but this may still have consequences for our nation - both in an immediate public health sense, and as we begin to see the spread of wider conspiracy theories in the UK. There does appear to be a strong link between those who are involved with anti-vaccine groups, and engagement with broader conspiracy theories.

One of the more vocal conspiracy theory movements in the USA is QAnon. Readers may have seen Jake Angeli, the ‘QAnon Shaman’ in his bison horns and fur storming into the US Capitol in January. QAnon was one of the first movements to propose the vaccine conspiracy theory involving Bill Gates and micro-chips, but its influence and theories encompass a wider range of topics. In her book, Going Dark published early in 2020, disinformation and extremism expert Julia Ebner describes the success of this group as ‘baffling’. She details the goals of the group’s small but vocal and growing UK offshoot Q Britannia as ‘to give the people of the UK somewhere to network, share information, archive and find ways to take back our country’.

This is the difficulty with conspiracy theorists, as opposed to vaccine hesitant people, and explains the need for us to engage with people as early on as possible, in an empathetic way as suggested by Professor Larson. By the time they reach the conspiracy theory movements they are seen, as CNN’s Don Lemon put it, as ‘literally nutty’ and it becomes as difficult for us to engage with them as for them to engage with us.

There is evidently an atmosphere of distrust and resentment brewing towards the government, and it will need to rebuild trust, with empathy and tech-savvy intelligence, before it can successfully conclude the vaccine programme, particularly if it wishes to eventually vaccinate children. If there is going to be a compulsory vaccine programme following an Act of Parliament - the messaging will be key to its success. The courts may well become involved if anti-vax groups seek to challenge an Act of Parliament, and will almost certainly be involved in the case of vaccine hesitant parents.

Another legal area in which arguments on this subject will play out is information regulation. In January 2021 Facebook, Instagram and Twitter took the drastic step of blocking Donald Trump, but since April 2020 Facebook has put warning labels on some posts and even banned anti-vax ads, much harmful content remains. Does Facebook therefore need to redesign its business model and algorithms to ensure it does not amplify this content? What are the ramifications for free speech and why are other extremist leaders not excluded from these platforms? Should Facebook just downgrade the malicious content? How can we encourage these companies to act, or should we legislate to force them to do so? I cannot pretend to have the answers to these questions, and any restrictions could just drive anti-vaxxers further into darker webspaces, like 4chan, which is already starting to happen in the UK.

Following the insurrectionist storming of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 the Community Security Trust (CST) published a blog highlighting posts on the website 4chan used by those in the UK who were eager and willing to replicate the actions of Trump’s supporters in the House of Commons. The CST stated that this is ‘yet another example of why internet regulation is urgently needed to help control the spread of online extremism, as Metropolitan Police Assistant Commissioner Neil Basu described’.

It’s important to remember that there is a difference between those who are sceptical of the new vaccines, and those who fervently believe that its introduction is an attempt to control their lives. What’s important now is how we respond to those who feel their concerns have not been heard to prevent further deaths from coronavirus but also perhaps even threats to our government and democracy.

Certainly, there are echoes of broader conspiracy theories in anti-vax theories. That the vaccine is going to be used with malicious or nefarious intent with the goal of exerting control by an elite, for example. If anti-vax conspiracy theories are becoming a gateway for people to become further involved with groups like Q Britannia, we need to learn the lessons of Trumpism, so that when the time comes to reap what we have sown the bad apples will have fallen away - whether that’s from lack of oxygen, effective intervention, or a combination of the two remains to be seen. Winning back the trust of those who may yet become involved in these movements via a sort of ‘anti-vax gateway’ is imperative.

I never met my other grandfather who arrived in this country on the Kindertransport, fleeing an extremist movement who were determined to disrupt liberal elites. I am certain that he would be wary of anti-vaxxers and conspiracy movements, but he would also be delighted that so far our country has been immune to the attacks on its values as seen in the USA in January 2021. It is my hope that we can prevent people from being sucked into extremism by finding empathy and by not simply dismissing the hesitant. Our vaccination programme may now be the trial run for an attempt at rebuilding trust in experts, and in our government and institutions.

Is failure to confront the root cause of vaccine hesitancy driving people towards anti-vax views? Natasha Isaac examines how pervasive conspiracy theories about coronavirus vaccines have become

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar