*/

On the Technology and Construction Court’s 150th anniversary, David Sawtell explains how the ORs and the TCC broke new ground

2023 marks the 150th anniversary of the creation of the office of ‘Official Referee’ (‘OR’), and the foundation of what we call today the Technology and Construction Court or ‘TCC’. This year has seen lectures, an exhibition and other events across the country marking the event, as well as the publication of a book celebrating its history. Looking back, the ORs and the TCC have been a driver for procedural innovation and legal development.

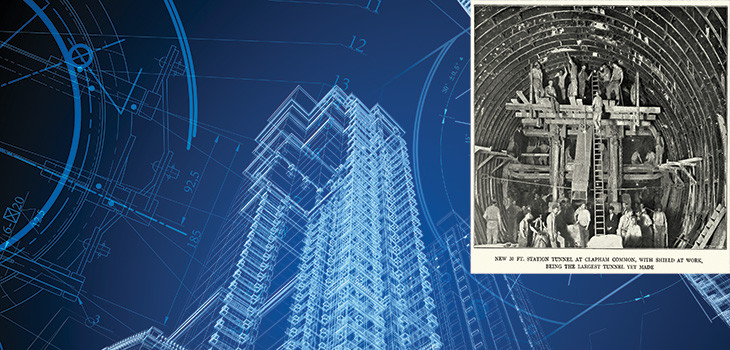

The nineteenth century was an era of much-needed modernisation and reform in civil procedure. Dispute resolution in technology, engineering and construction had lagged far behind the rapid developments in those sectors. Macintosh v The Great Western Railway Company (32 L.J. Ch.412) is a notorious, but not isolated, example: for money that became due in 1838, the contractor’s Bill of Complaint was filed in the Chancery in 1847; the Vice-Chancellor only ordered an enquiry in 1855, which took nearly eight years to complete; before this was overturned on appeal in 1863, sending the matter back to the start again.

The Royal Commission appointed in 1867 recommended the creation of a new form of dispute resolution, loosely modelled on arbitration, that could address scientific, technical and detailed factual issues which a jury trial could not satisfactorily resolve. The Judicature Act of 1873 created the Official Referees; subsequent legislation over the next 100 years expanded their jurisdiction, until the Courts Act 1971 re-cast them as full members of the judiciary. In 1998, they were fully assimilated into the High Court, assuming the name ‘Technology and Construction Court’.

The Official Referees and the TCC were innovators in civil procedure. The famous ‘Scott Schedule’ was the creation of George Scott KC, an Official Referee from 1920 to 1933, who adapted the surveying practice of dilapidations schedules. Sir Francis Newbolt KC outlined the need for expedition avoiding unnecessary cost in an important article, ‘Expedition and Economy in Litigation’ (1923) 39 LQR 427, that echoes the Woolf Reforms of the 1990s: procedural discussions, single joint experts and trials of preliminary issues were all features in his subsequent ‘Scheme’. Since the 1980s, the ORs and the TCC have led the way in technology and digital innovation, with the first ‘paperless trial’ taking place in 1995 in John Mowlem & Co v Eagle Star and others (1993) 62 BLR 126. The TCC heard the first Building Information Modelling (‘BIM’) case in the UK in Trant Engineering Ltd v Mott MacDonald Ltd [2017] EWHC 2061 (TCC), raising issues about access to design data that resonate across many technology disputes.

The ORs and the TCC amount to more than the sum of their procedural and doctrinal innovation: they are also the product of the extraordinary individuals who have sat and practiced there. One of the most remarkable was Sir Brett Cloutman, VC, MC, QC. Serving on the Western Front in the First World War with the Royal Engineers, he won the last Victoria Cross awarded during the First World War: he swam under the Quartres Bridge under heavy machine gun fire, and cut the wires to explosive charges. He served again in the Second World War, before taking silk in 1946 and being appointed an OR in 1948. Today, the TCC has contributed a number of current Lord Justices of Appeal, and with Dame Sue Carr, the first woman to serve as Lady Chief Justice since the inception of the office.

Dispute resolution in UK construction was transformed by the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 and the introduction of compulsory statutory adjudication. Its success (and subsequent adoption across large parts of the common law world) was far from certain, as it was unclear if adjudication decisions would be enforced. Starting with the seminal decision of Dyson J (as he was then, as the first judge in charge of the newly named TCC) in Macob Civil Engineer Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd [1999] BLR 93, it was confirmed that the TCC would robustly support adjudication as a process. The TCC has created a body of case law that has given shape to a truly revolutionary form of rapid dispute resolution, re-shaping modern construction law.

Many of the highest profile and leading cases in English private law began before the ORs and the TCC. The development of the scope of the duty of care in tort for economic loss was shaped by the decisions in Anns v Merton, Peabody v Sir Lindsay Parkinson and Murphy v Brentwood District Council: all of them started before the ORs. It is unsurprising that the TCC has recently dealt with issues arising from the duty of care of a structural engineer, as well as the important changes made to the Defective Premises Act 1972 by the recent Building Safety Act 2022 in URS Corporation Ltd v BDW Trading Ltd [2023] EWCA Civ 772; the decisions of the court were upheld on appeal to the Court of Appeal this summer.

The ORs and the TCC have also demonstrably shaped English contract law. The TCC heard the first instance trial in RTS Flexible Systems Ltd v Molkerei Alois Müller GmbH & Co KG (UK Production) [2008] EWHC 1087 (TCC) (first instance); [2010] UKSC 14 (Supreme Court); it was subsequently heard on appeal in the Supreme Court, which re-stated the modern law on contract formation. The law on competing express terms for quality was re-considered and definitively set out in the offshore windfarm case of MT Højgaard A/S v E.ON Climate & Renewables UK Robin Rigg East Ltd [2014] EWHC 1088 (TCC) (first instance); [2017] UKSC 59 (Supreme Court). The English law on liquidated damages in circumstances where the contractor never achieves completion was recently re-examined by the Supreme Court in Triple Point Technology Inc v PTT Public Company Ltd [2018] EWHC 1398 (TCC) (first instance); [2021] UKSC 29 (Supreme Court), in a dispute arising from commodities trading software; again, the case had begun in the TCC.

What unifies all of these cases is their origins in technical and factually complicated disputes, from which important points of private law were distilled and adjudicated upon by a cadre of specialist judges at first instance. It is the combination of procedural innovation, willingness to adapt and judicial excellence, supported by a specialist Bar, that has contributed both to the longevity and the success of the TCC today.

The need for a procedurally efficient court with experience of factually and legally complicated disputes is as strong as ever. The ORs and the TCC have broken new ground through the high profile and critical cases that have come into their lists. Looking into the future, the TCC has shown itself to be a past master of innovation.

2023 marks the 150th anniversary of the creation of the office of ‘Official Referee’ (‘OR’), and the foundation of what we call today the Technology and Construction Court or ‘TCC’. This year has seen lectures, an exhibition and other events across the country marking the event, as well as the publication of a book celebrating its history. Looking back, the ORs and the TCC have been a driver for procedural innovation and legal development.

The nineteenth century was an era of much-needed modernisation and reform in civil procedure. Dispute resolution in technology, engineering and construction had lagged far behind the rapid developments in those sectors. Macintosh v The Great Western Railway Company (32 L.J. Ch.412) is a notorious, but not isolated, example: for money that became due in 1838, the contractor’s Bill of Complaint was filed in the Chancery in 1847; the Vice-Chancellor only ordered an enquiry in 1855, which took nearly eight years to complete; before this was overturned on appeal in 1863, sending the matter back to the start again.

The Royal Commission appointed in 1867 recommended the creation of a new form of dispute resolution, loosely modelled on arbitration, that could address scientific, technical and detailed factual issues which a jury trial could not satisfactorily resolve. The Judicature Act of 1873 created the Official Referees; subsequent legislation over the next 100 years expanded their jurisdiction, until the Courts Act 1971 re-cast them as full members of the judiciary. In 1998, they were fully assimilated into the High Court, assuming the name ‘Technology and Construction Court’.

The Official Referees and the TCC were innovators in civil procedure. The famous ‘Scott Schedule’ was the creation of George Scott KC, an Official Referee from 1920 to 1933, who adapted the surveying practice of dilapidations schedules. Sir Francis Newbolt KC outlined the need for expedition avoiding unnecessary cost in an important article, ‘Expedition and Economy in Litigation’ (1923) 39 LQR 427, that echoes the Woolf Reforms of the 1990s: procedural discussions, single joint experts and trials of preliminary issues were all features in his subsequent ‘Scheme’. Since the 1980s, the ORs and the TCC have led the way in technology and digital innovation, with the first ‘paperless trial’ taking place in 1995 in John Mowlem & Co v Eagle Star and others (1993) 62 BLR 126. The TCC heard the first Building Information Modelling (‘BIM’) case in the UK in Trant Engineering Ltd v Mott MacDonald Ltd [2017] EWHC 2061 (TCC), raising issues about access to design data that resonate across many technology disputes.

The ORs and the TCC amount to more than the sum of their procedural and doctrinal innovation: they are also the product of the extraordinary individuals who have sat and practiced there. One of the most remarkable was Sir Brett Cloutman, VC, MC, QC. Serving on the Western Front in the First World War with the Royal Engineers, he won the last Victoria Cross awarded during the First World War: he swam under the Quartres Bridge under heavy machine gun fire, and cut the wires to explosive charges. He served again in the Second World War, before taking silk in 1946 and being appointed an OR in 1948. Today, the TCC has contributed a number of current Lord Justices of Appeal, and with Dame Sue Carr, the first woman to serve as Lady Chief Justice since the inception of the office.

Dispute resolution in UK construction was transformed by the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 and the introduction of compulsory statutory adjudication. Its success (and subsequent adoption across large parts of the common law world) was far from certain, as it was unclear if adjudication decisions would be enforced. Starting with the seminal decision of Dyson J (as he was then, as the first judge in charge of the newly named TCC) in Macob Civil Engineer Ltd v Morrison Construction Ltd [1999] BLR 93, it was confirmed that the TCC would robustly support adjudication as a process. The TCC has created a body of case law that has given shape to a truly revolutionary form of rapid dispute resolution, re-shaping modern construction law.

Many of the highest profile and leading cases in English private law began before the ORs and the TCC. The development of the scope of the duty of care in tort for economic loss was shaped by the decisions in Anns v Merton, Peabody v Sir Lindsay Parkinson and Murphy v Brentwood District Council: all of them started before the ORs. It is unsurprising that the TCC has recently dealt with issues arising from the duty of care of a structural engineer, as well as the important changes made to the Defective Premises Act 1972 by the recent Building Safety Act 2022 in URS Corporation Ltd v BDW Trading Ltd [2023] EWCA Civ 772; the decisions of the court were upheld on appeal to the Court of Appeal this summer.

The ORs and the TCC have also demonstrably shaped English contract law. The TCC heard the first instance trial in RTS Flexible Systems Ltd v Molkerei Alois Müller GmbH & Co KG (UK Production) [2008] EWHC 1087 (TCC) (first instance); [2010] UKSC 14 (Supreme Court); it was subsequently heard on appeal in the Supreme Court, which re-stated the modern law on contract formation. The law on competing express terms for quality was re-considered and definitively set out in the offshore windfarm case of MT Højgaard A/S v E.ON Climate & Renewables UK Robin Rigg East Ltd [2014] EWHC 1088 (TCC) (first instance); [2017] UKSC 59 (Supreme Court). The English law on liquidated damages in circumstances where the contractor never achieves completion was recently re-examined by the Supreme Court in Triple Point Technology Inc v PTT Public Company Ltd [2018] EWHC 1398 (TCC) (first instance); [2021] UKSC 29 (Supreme Court), in a dispute arising from commodities trading software; again, the case had begun in the TCC.

What unifies all of these cases is their origins in technical and factually complicated disputes, from which important points of private law were distilled and adjudicated upon by a cadre of specialist judges at first instance. It is the combination of procedural innovation, willingness to adapt and judicial excellence, supported by a specialist Bar, that has contributed both to the longevity and the success of the TCC today.

The need for a procedurally efficient court with experience of factually and legally complicated disputes is as strong as ever. The ORs and the TCC have broken new ground through the high profile and critical cases that have come into their lists. Looking into the future, the TCC has shown itself to be a past master of innovation.

On the Technology and Construction Court’s 150th anniversary, David Sawtell explains how the ORs and the TCC broke new ground

The Bar Council is ready to support a turn to the efficiencies that will make a difference

A £500 donation from AlphaBiolabs has been made to the leading UK charity tackling international parental child abduction and the movement of children across international borders

By Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth Management

Marie Law, Director of Toxicology at AlphaBiolabs, examines the latest ONS data on drug misuse and its implications for toxicology testing in family law cases

An interview with Rob Wagg, CEO of New Park Court Chambers

What meaningful steps can you take in 2026 to advance your legal career? asks Thomas Cowan of St Pauls Chambers

With at least 31 reports of AI hallucinations in UK legal cases – over 800 worldwide – and judges using AI to assist in judicial decision-making, the risks and benefits are impossible to ignore. Matthew Lee examines how different jurisdictions are responding

Ever wondered what a pupillage is like at the CPS? This Q and A provides an insight into the training, experience and next steps

The appointments of 96 new King’s Counsel (also known as silk) are announced today

Resolution of the criminal justice crisis does not lie in reheating old ideas that have been roundly rejected before, say Ed Vickers KC, Faras Baloch and Katie Bacon

With pupillage application season under way, Laura Wright reflects on her route to ‘tech barrister’ and offers advice for those aiming at a career at the Bar